How Reading Rilke Helped Me Deal With Grief

Months into the radio silence, Omi finally bid his adios. “I hope you find happiness, and I know you will,” he wrote in a goodbye email I deleted afterward. That was more than two months ago, and it would be the last time I would ever hear from him. Omi was someone I met through a language exchange app, eventually turning into my best friend and hermano for over two years. But we were quite the polar opposite; in close proximity, we were neither. He was an actor doing independent films in Mexico City. Devil-may-care he was, jet-setting around Europe even in the height of a global pandemic. And I was a struggling writer in Manila in the hope of finding a literary agent — introverted, enigmatic, head always buried in a hand-me-down copy of The Atlantic.

When I had told him to keep the door open, casually hoping he would change his mind and ask me to “fuck it, dude, forget it,” I felt bitter by the sudden turn of events. The nostalgic memories of a past long gone and the sweet might-have-beens threatened to resurface. It felt hard to let go and move forward with my life, and there were days I couldn’t get out of bed. And so like many bookworms, I turned to literature to find solace, finding myself reading Rilke’s works.

Known for the collections Letters to a Young Poet and The Book of Hours, Rainer Maria Rilke was a celebrated German poet.

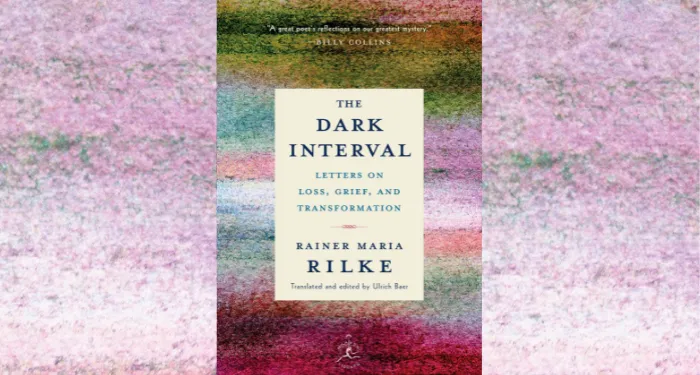

In his book The Dark Interval: Letters on Loss, Grief, and Transformation, which was compiled in 2018, the preface says that Rilke wrote more than 14,000 letters to friends and people whom he met briefly. Twenty-three of them are about loss, which forms The Dark Interval. In the book, he addresses friends and former lovers who are going through a difficult time in their lives. “What can you say in the face of loss, when words seem too frail and ordinary to communicate our grief and soothe the pain?” writes the translator, Ulrich Baer.

Though Rilke originally wrote in German and French, his English-translated works never lost their wisdom. Reading his intimate letters, written more than a century ago, felt like being consoled by a close friend. And though a “friendship breakup” isn’t as harrowing as, say, death, reading his prose compels me to find acceptance. “You must continue his life inside of yours insofar as it was unfinished; his life has now passed onto yours. You, who quite truly knew him, can quite truly continue in his spirit and on his path. Make it the task of your mourning to explore what he had expected of you, had hoped for you, had wished to happen to you. If I could just convince you, my dear friend, that his influence has not vanished from your existence,” Rilke writes, almost admonishing me.

Much has been said about the healing power of literature; many readers find escape and comfort in books in times of need. Rilke captures for me the feelings I can’t put into words; I let his intimate letters steer me through my grief. Because indeed, what could someone really do in the face of an agonizing loss, in the middle of a pandemic when many friendships crumbled?

In 2019 B.C. (Before COVID), Omi and I had found each other by chance. I wasn’t really looking for friends at the time as I believed I was fine with the few ones I had, but I downloaded HelloTalk anyway to practice my Spanish. “Buscando a alguien para practicar mi inglés,” one Argentinian man wrote in a post. “Actor for a Netflix TV series,” put another one in his bio; I was immediately intrigued and sent a too forward and maybe embarrassing “hola, wey!” But little by little, the actor and I progressed as mejores amigos: a nonbinary Filipino and a cisgender Mexican as friends. It was straight out of a telenovela.

In the next two years, I grew fond of him. We shared a lot of milestones, from his graduation and our birthdays — he made me a magic wand inspired by a book I loved — to our plans in the next 30 years of our lives. And much to my surprise, he was a reader, too, even gobbling up the poetry collection I wrote sometime ago.

“I’ll try to find the magic wand, and if I do, I’ll send it to you,” he wrote to me two years later in his last message as I asked about the damn thing (he couldn’t send it to me the first time around). But he never wrote back. The realization then, no matter how clichéd it was, hit me that people really come and go in life. As I paged through Letters to a Young Poet once again, Rilke wrote, “let life take its course. Believe me: life is right, whatever happens,” which made the rejection sting a lot less.

Before I mustered the courage in sending Omi an email after the falling out, there had been months of no contact. But despite all the bitterness and anger we both harbored, his response was nonchalant, even wishing me well in life. “In my case what had died for me, so to speak, had died into my own heart…” Reading this one from Rilke, I wondered why even a failed friendship would scar you for life? That despite the brief time you and the person shared, they bleed into other aspects of your life? I just didn’t want to think about Omi anymore. I’d like to think I was done grieving. “It was deeply moving to feel that he now existed only there,” borrowing words from Rilke.

As I purged all the texts Omi and I sent to each other over the past two years, I couldn’t help but feel bittersweet. I realized now that, in a world where men tear each other down thanks to patriarchal masculinities, what he and I had was rare. I will always remember it. And though we don’t talk anymore, and he found better companies to enjoy, I’m still grateful that, once upon a time, we crossed paths. “While I am completely engulfed in my sadness, I am happy to sense that you exist,” Rilke writes, giving me hope that someday, after the dust has settled, maybe my hermano will say hola again.