Peripheral Intimacy in Neil Gaiman’s THE VIEW FROM THE CHEAP SEATS

A lot has been written about what the Internet has done to memoirs and creative nonfiction—that our hundred and forty character bare-all confessions have both escalated the intimacy of the content and desensitized us to it. Are we hungry for secrets? Do we expect every personal essay to take us back to our slumber party years when we’d sit on our pillows and open up our hearts like the bags of Cheetos we had nearby in great numbers? I can’t speak for the rest of the class here, but I think I do. I do expect those things. I recently experienced this with Neil Gaiman.

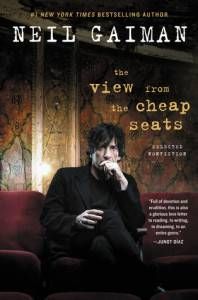

I bought his first collection of nonfiction, The View from the Cheap Seats, with nothing short of atomic bombs of delight exploding in the New Mexico of my chest. I’m a curious soul, interested in people and obsessed with context. So holding this massive volume of Real Life Neil Gaiman, I was just about over the moon. I cracked it open, ready to stay up past my bedtime to pass Neil the Cheetos and listen as he shared his deepest fears, most embarrassing moments, and secret crushes.

I bought his first collection of nonfiction, The View from the Cheap Seats, with nothing short of atomic bombs of delight exploding in the New Mexico of my chest. I’m a curious soul, interested in people and obsessed with context. So holding this massive volume of Real Life Neil Gaiman, I was just about over the moon. I cracked it open, ready to stay up past my bedtime to pass Neil the Cheetos and listen as he shared his deepest fears, most embarrassing moments, and secret crushes.

As I worked my way through the essays, it became clear this was not going to be that kind of slumber party. Not exactly.

The first time I encountered Neil Gaiman, I didn’t know who he was or what he was all about. I was in seventh grade, and head over heels in love with SimCity2000. I’d cheat code the heck out of it because I’m an idiot at most things including city planning, and with my pile of ill-gotten Simoleons I would stack my simulated city with libraries until they outnumbered my residents. I am what I am.

I also liked to click on everything I could, because as I said I’m curious. Something special happens when you click on your library—you have the option to “ruminate.” It was a big word for me, but I clicked it anyway. And that’s how I learned that “ruminate” is a just another way of saying “read a short essay by Nail Gaiman about the wonder and terror and personalities and anthropomorphic essence of cities.” It was incredible, and I loved it and was kind of shaken by it. But I loved it. I ruminated often.

Even before I was a fully bloomed reader, I was a book lover. I know how backward that sounds, believe me. I would ruminate over the white shelf in our basement that held my dad’s science fiction and fantasy collection. I would admire the spines and the covers and wonder what secrets they would tell me if these books and I were sitting on our pillows swapping stories late into the night. But I hesitated to find out; I don’t really know why. There was too much SimCity2000 to play, I suppose. Too many Cheetos to crunch.

Neil Gaiman also loves books. (see also: surprise!) He has loved reading and books for pretty much the whole of his life, and most of the essays collected in The View from the Cheap Seats are book-related. Most are introductions, many are speeches, some are interviews and short works of journalism.

And as I kept going, as I kept turning the pages, I realized that was I was actually doing was following Neil as he ruminated through the stacks of the SimLibrary central to his career, his character, his everything. He was ruminating. And he was letting us ruminate with him.

John Waters gave famous advice about what to do if you accept an invitation upstairs with someone you might want to spend a night with. Let’s assume they do indeed own books, and you do indeed stay the night, and they do indeed get up for a drink of water and you have just enough time to scamper to their shelf and admire the spines and covers of their personal collection. That, my friends, is intimacy; that’s vulnerability. That’s rumination.

This changed the way I finished reading this book. I forgave in an instant what at first felt like too much psychic distance for my taste. As he pointed out volumes or pulled them from the metaphysical shelf as we passed together, I took them in my arms lovingly. It’s how I found The Einstein Intersection , The Kryptonite Kid, and many many more. He was giving gifts.

In addition to introducing us to the books he loved, Neil Gaiman also introduces us to people living and dead that he loved in various ways. The essays he wrote for Amanda Palmer each admire her differently from different points on their timeline (they’re married now, in case you did not know). His words for Terry Pratchett capture a life from different points on a timeline, too. (He has since passed away, in case you did not know.) All are tender, honest, and celebratory even when weighed down with sadness. I dare you to read “Jack Kirby: King of Comics” and not find yourself on fire for the comic book legend on whose shoulders Neil stood to recreate Sandman. I double dog dare you to read “Hi, by the Way” or its successor and not feel even slightly tipsy by proxy from sexy Spanish wine and the madcap beauty of Neil’s friendship with Tori Amos. I triple dog dare you to read “So Many Ways To Die in Syria Now: May 2014”, for which Neil turns down the volume on his writing at the sentence level in order to lift up the voice of the subject—human beings crying out for help in real-time—and not feel called to action. He loves these refugees, and hopes we will love them too and will extend a hand in whatever way we can. These essays are all about love, and though the intimacy seems peripheral it’s there in great supply.

And maybe there’s wisdom in keeping the intimacy somewhat oblique. In “Waiting for the Man” Gaiman interviews Lou Reed, a personal and creative hero of his. As Reed moves from periphery into plain sight—warts and prickliness and all—Neil has a moment of understanding that this is probably too close for comfort. “I’d been around long enough,” he writes, “to know the person isn’t the art…I went back to being a fan, happy to celebrate the magic without the magician.”

My craving for a Neil Gaiman tell-all may never be satisfied. I’m okay with that now. We have his stories, marbled to varying degrees with his beliefs, his fears, his memories, his secret crushes, his not secret crushes, his dreams, and of course of course of course his magic. You can keep your Cheetos. Just pass me more of that instead.

Actually who am I kidding, I’ll take some Cheetos, too.