Like Opening a Time Capsule: On Marginalia And Guilt

While reading books, I pay attention to marginalia. With wonder, I touch a finger to inscriptions, annotations, and doodles. As someone who has scribbled in books myself, I spend extra time with sections the scrawlings reference. Although my marginal notes, after graduating, shifted from thinking-on-the-page to celebrating beauty. In the margins, my signature moves include hearting sentences and drawing lines alongside passages I love.

Last year, I texted fellow bibliophiles to ask whether they wrote in their books. To my surprise, everyone said no, except my soul sister, who sometimes stars and underlines text in pencil. Of course, guilt and shame promptly RSVPed. Suddenly, my pen began to stutter next to breathtaking words.

First, I stopped writing in hardcovers, then paperback prose, then poetry. Two Aprils ago, I quit marginalia and started using sticky flags instead, which also stirs up guilt when I linger on it. The last book I peppered with pen was Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers by Jake Skeets. One exception: During The Sealey Challenge, I drew a heart in Layli Long Soldier’s WHEREAS while waiting for more Post-its to arrive.

Over a decade ago, one sunny college afternoon at Schuler Books, I sat on the patio, manufacturing vitamin D and penning definitions for new-to-me words next to dense text. It took forever to finish a page. Eventually, I gave up knowing every word and gleaned meaning from familiar ones. Is this how marginalia catches a bad reputation? People associate it with required reading and pop quizzes and formal essays and caffeine-filled nights, and they want to forge as much distance as possible between them and those memories.

Looking back at the texts I didn’t trade in ASAP at the university bookstore, I kept two marginalia-thick books I presented on. Nothing like potentially being shamed in front of a classroom full of peers to terrify you into thorough studying.

For an undergraduate project about writing style, I riddled my copy of The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros with notes about alliteration, figurative language, gender, and repetition. I underlined beautiful sentences in pen. Judging from the generous attention of my writing utensil, I sense that “Hairs” and “My Name” made me feel less alone in the world.

For a graduate poetry workshop, my partner and I led the class discussion for Lighthead by Terrance Hayes. My paperback contains paragraphs of cursive from first impressions to detailed research. In pencil, I asked questions in blank spaces. I circled words. Some rhyme, like capsized and side, and some don’t, like weight, fire, and light. At the bottom of pages, I jotted words: dreams (three times), blue (twice), passage, shadow, alligator.

Revisiting these books feels like opening a time capsule. Between the pages, a six-page draft of a paper that trails off with “In the last vignette,” a boarding pass from San Francisco to Pittsburgh, and a receipt from an Ohio Panera Bread. A cerulean Post-it with two lackluster lines that never spun into a poem sticks inside a book flap.

Despite part of me screaming, Destroy those lines and that English assignment, I don’t experience a smidge of guilt while encountering younger me. I want to wave wildly to myself, blow myself kisses, and slip myself all the cash in my wallet so I can purchase more poetry collections and treat myself to dinner instead of filling up on old, floppy fries from the basket in the hot window and ramekins of soup during my bartending shifts.

Even if our school days have ended, our learning continues. As my go-to dream dictionary stresses, “Life is school.” Dreaming is school. Pleasure reading is school — an independent study of sorts. Whether I adore a book or not, everything I read teaches me, so why not scribble on the pages of my personal collection? Marginalia is proof that I’m here, that I was present, and that I’m growing.

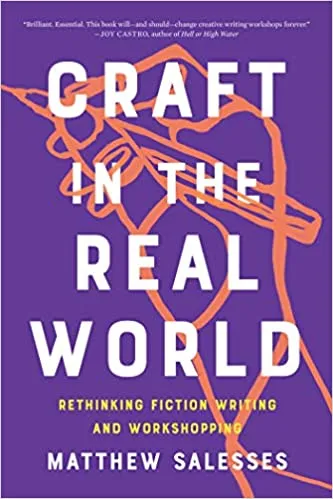

After 14 long marginalia-less months, I’m emerging from this phase, and I recognize the universe easing me in my heart’s direction. Since February, Craft in the Real World waits on Blue, my high-priority to-be-read table, and I know in my reader’s soul that my fingers will ache for every clicky pen under the moon while reading Matthew Salesses’s book. So far, I’ve finished two essays published in Literary Hub and No Tokens, and they brimmed my eyes with tears. I, nodding along, jiggled my brain. I saved dear-to-me quotes. I shared the pieces with teacher friends.

While shopping online in March, I ordered a previously owned copy of Picture Bride from Eastwind Books of Berkeley. When it arrived, I opened Cathy Song’s debut poetry collection, and it teemed with marginal notes. Someone numbered the lines of “Primary Colors” and bracketed marine-colored shells in the ending of “Easter: Wahiawa, 1959”: “The scattering of the delicate / marine-colored shells across his lap / was something like what the ocean gives / the beach after a rain.” Both the book and I are Virgos and love Hawai‘i. It felt like a nod from the galaxy.

Lately, I’ve been rereading the opening poem of Inheritance. In “Since I quit that internet service,” Taylor Johnson writes, “Close as in when I stood up, let one deep exhale, when I came to the lines Of all fearless happiness / from which reaches my life I sing — and find it underlined by a beloved stranger. It’s like turning the record over. Knowing you’re hearing what I’m hearing.”

All of this to say, any guilt over my marginalia has dissipated. I see myself reaching for my book stack and a pen, being a beloved to a stranger, but mostly being a beloved to myself.