Following the STATION ELEVEN Trail

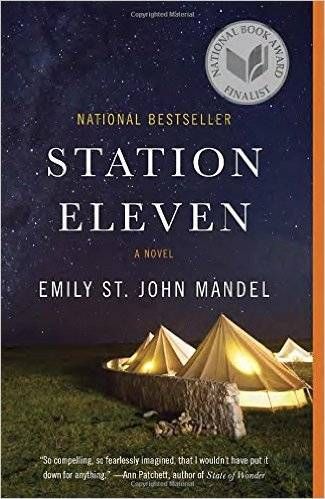

The Traveling Symphony ran into me just a few days outside of Traverse City. Or rather, I ran into them, across a chasm of time and fiction, when I realized that their story, which I’d picked up because it is a celebrated post-apocalyptic novel, moved through territory immediately around me, up and down Michigan’s northern coast.

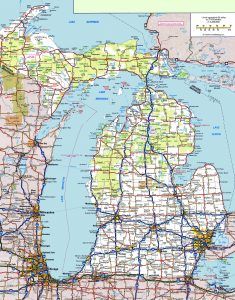

It’s an eerie feeling, reading about your town as a site of a plague. Fairly, the whole world is the site of a plague in Station Eleven, though the character stories it focuses on are more localized: to Toronto first, but then to the Michigan shore, in a line from Mackinaw City down to Severn City that basically sticks to the edge of the mitten’s fingers and moves right through Traverse City in both directions.

It’s an eerie feeling, reading about your town as a site of a plague. Fairly, the whole world is the site of a plague in Station Eleven, though the character stories it focuses on are more localized: to Toronto first, but then to the Michigan shore, in a line from Mackinaw City down to Severn City that basically sticks to the edge of the mitten’s fingers and moves right through Traverse City in both directions.

If you’re not familiar with the book: it focuses on a set of actors, and the people in the starring and supporting roles of their lives, before and after the Georgian flu rapidly decimates 99% of the world’s population. Those who survive hole up where they can: in makeshift towns built around strong personalities both benevolent and bent, or as travelers and scavengers on the road.

Central in both times are Kirsten, Tyler, Jeevan, and Clark, who were all connected to an enigmatic actor who died on stage just as the flu was ramping up. Kirsten is part of the Traveling Symphony in the world after the plague. The troupe performs Shakespeare and beloved concertos in Michigan; she’s the one whose Traverse City memories butted into my own.

I was hooked.

But here’s the problem with a book that moves through towns that you know: when it changes the details, its new world becomes a puzzle that you need to solve. New Petoskey was easy enough to locate—it’s the revived version of the current town. Traverse City and Mackinaw City kept their names. But what about Severn City, where the Museum of Civilization is? And St. Deborah by the Water, where the Traveling Symphony encounters the Prophet and everything goes awry? These are not currently real places. So where do they fit on the map?

There are clues: Severn City is outside of a semi-major town, with a regional airport big enough to host ocean-crossing jets. The airport has multiple terminals, but it’s also a stone’s throw from the edge of the woods and not far from the lake. It is potentially wholly an invention; the book mentions that it’s a new airport. Save that detail—and the fact that it’s meant to have held its name from before the plague—it would be easy to peg it as Cascade, just outside of Grand Rapids, which hosts the Gerald R. Ford International Airport, whose layout basically fits the bill.

St. Deborah by the Water is a bit trickier to peg. It’s far enough outside of Traverse City that the Traveling Symphony refers to TC as stop in recent memory—getting stale, though, not fresh enough to be measured in days. I rejected the Great Michigan Read map on that basis. It placed St. Deborah by the Water just on the other side of the Leelanau Peninsula, around Frankfurt—and what shenanigans are these?! Realistically, that’s a straight shot, a matter of a day or two of travel on foot, and far, far away from the Severn City Airport, where the book ends up and which is just a day or two from St. Deborah, book events–wise. What’s more: Frankfort doesn’t have an IHOP, which is mentioned several times as an active site in St. Deborah by the Water. I needed the IHOP as proof.

…Does this sound obsessive? Well. I guess it is. But I wanted to picture every element of the story accurately, and given how in reach the Traveling Symphony’s stops were for me, precision seemed possible.

I did something a little silly: I Googled IHOPs in places that fit the book’s descriptions of St. Deborah by the Water, in towns close enough to the big lake that the water glinted from their centers (5 miles away, the book says), and that were near to a national forest. Muskegon—just over a hundred miles from Traverse City—was the only town that fit the bill in size, proximity, and IHOP possession.

I’d never been there.

I’m a fan of literary pilgrimages; this one would just be a day trip. I resolved to go and check it out.

I filled the car with gas, decided against making a temporary “Survival is Insufficient” bumper sticker, loaded up some audiobooks on my phone, and took off. Audible polished off the last few chapters for me en route; in fact, I finished Station Eleven in Muskegon, while my antique store to antique store search for a paperweight with a cloud inside of it was already underway.

Muskegon seemed to mesh well with the story—and not only because I was wholly immersed in the book for a portion of my driving-around time there. Its high-treed cemetery just off of the town’s center was both eerie and beautiful—a little too wide to fit the church cemetery that figures in to the Prophet’s punishments, but quiet enough to mute noises and wander away from the active world in. Its line of buildings above the waterline seemed like a safe place to hole up. In the August humidity, on a slow Saturday, it even had the air of a place that could weather the apocalypse; some aging buildings seemed like they already had.

I found a paperweight that sort of fit the book’s description and took it home for my own mini Museum of Civilization (though, laden with books as it is, my collection might be of more interest to New Petoskey’s collectors), driving through the Manistee National Forest on my way. I did not take pictures—it felt irruptive to do so, and anyway this is a world without the plague, the alternate universe that Kirsten and another troupe member trouble over. The images wouldn’t be exact.

And it might not have been the place that Emily St. John Mandel had in mind, anyway—I don’t know. Muskegon was a close enough fit for me to be able to resolve the book’s images to the Michigan of my experience. You could understand, in the Manistee forest, why a troupe of actors would want to avoid those tree lines, and how a home could go twenty years undiscovered in those woods. You could imagine, crossing the bridge into Muskegon’s downtown, where a young sentry might stand. You could squint your eyes just a bit on a quiet street and envision both the before and after.

But you could also see and participate in the life of the city free from the novel’s Georgian flu. Post-apocalyptic novels remind you of what’s important—the connections that we build, the treasure of prioritizing a call to say “I love you” over one that focuses on work matters. How “everything happens for a reason” is sometimes a dangerous mantra that enables us to do unthinkable, unreasonable things. They remind us of the small miracles behind the resources that we take for granted: electricity, running water, air travel, tetanus shots. The gas in my car, with its shelf life that I never think about. Newspapers. GPS. Bottled water.

Even on a dreary day in a common enough town, these aspects of our everyday existence seemed precious. You just need to juxtapose them to Station Eleven‘s “after” to get it—and then you, like the residents of that imagined world in the sky, want nothing more than to return home.