Eulalia!: A MOSSFLOWER Memory

While we at the Riot are taking this lovely summer week off to rest (translation: read by the pool/ocean/on our couches), we’re re-running some of our favorite posts from the last several months. Enjoy our highlight reel, and we’ll be back with new stuff on Wednesday, July 8th.

This post originally ran May 22, 2015.

_________________________

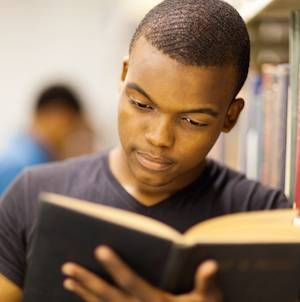

The end of my eighth-grade year was marked by two things: June’s hateful summer sun, and afternoon rides on buses that whined and belched like Jurassic sauropods. I despised those buses, with their emissions and squeals and oddly stained plastic seats. They would rumble down one of my hometown’s major streets, stopping just enough times for rowdy groups of middle and high schoolers who frequented the back of the bus to get too loud and catch shouted admonishments from the elders who sat at the front. I could usually be found lurking around the rowdy group, a “good kid” with a decent GPA who played along because it was better to be at the edge than to cross that thin line to outsider status.

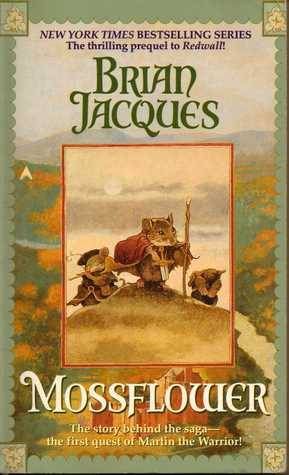

I had always loved books, though I could never find time to read them on the bus. My parents’ mantle was covered with prizes I had been awarded for my reading prowess. But those same parents, who knew that a young black man spending his time reading books with sword-bearing white people on the cover wasn’t always the most direct path to academic success, had steered my literary consumption in more practical directions. One of my classmates had been engrossed in a book that reminded me of my forbidden reading loves, only instead of white people on the cover, there were mice. His face never left its pages–to the detriment of his math studies. Seeing his enjoyment, I decided to ask him if I could borrow the book for a few days. The closer he got to the end, the more apprehensive I became.

Here is where fate first intervenes: The day we found ourselves in detention together (because of missed math homework) was the very day he finished the book. I gave my ask and he told me, with the air of a child who gets everything that he wants and thus doesn’t care about anything in particular, that I could have the book because it was old anyway. That was my introduction to Brian Jacques’ Mossflower, and I went into his hero creature filled world with glee in my heart.

Here is where fate first intervenes: The day we found ourselves in detention together (because of missed math homework) was the very day he finished the book. I gave my ask and he told me, with the air of a child who gets everything that he wants and thus doesn’t care about anything in particular, that I could have the book because it was old anyway. That was my introduction to Brian Jacques’ Mossflower, and I went into his hero creature filled world with glee in my heart.

I crossed the thin line that day. Unable to deal with the volume at the back of the bus, I moved to the front. Someone made a Rosa Parks joke, but everyone else seemed unbothered. What frightened me next was getting off at the transfer, where all of the toughest and most frightening reform school kids would hang out. Mossflower, however, was more compelling. Would Martin and Gonff escape Tsarmina’s clutches? Was Fortunata a sorceress? I kept reading because I had to know.

There was a bench at the transfer, stained with the sins of high school children. I sat there, book in hand, barrelling through the eventual prison break, and followed along as a group of woodland creatures fomented a revolution. I was completely engrossed despite my teenage fears. At least, until fate decided to interrupt me once again.

The girl that sat down next to me smelled like Now and Laters and hair products. Her school uniform was in a state of disarray, and her lips were plump with gloss. Two friends flanked her, equally stunning with their braids, jewelry, and candy scents. I prayed that they couldn’t hear my teeth chattering.

“What you reading?” the ringleader asked, genuinely interested. She made popping noises with her gum because she could.

“A book,” I replied (Stupid!), holding it up so that she could see the cover. She studied it for a moment. In the background, her friends were engaged in a discussion about which of the boys currently crossing the street was the most handsome.

“That’s a weird looking book,” she said. My heart dropped to my feet, either because she had deemed my book strange or because she disapproved of me as a cluster of breathing cells. “What’s it about?”

“It’s like an adventure story,” I said, somewhat surprised that I was able to form sentences. “This mouse gets locked up in a dungeon by an evil queen. The queen’s a wildcat. He and his friend break out of jail, and there’s probably going to be a big fight where they break the other folks out of the dungeon too, and save the woodlands.”

“For real? My cousin is in jail. I wish somebody would break him out.” She looked at me for a moment, and I tried not to melt into a puddle of proteins. “I just came over here to see what you was reading. You looked like it was real good. If I see you after you finish your book, can I borrow it?”

“You can have it,” I promised her. She smiled at me, then went to join her friends, sliding on her tough mask and punching one of the handsome boys in the arm.

I never saw her again. But every so often, I think on the effect of this moment on the trajectory of my life, and consider reaching out to those who reassured me when I was most afraid of belonging. Before I do, though, I catch myself, and realize that even though the events were important, discovering a book that I loved is what mattered most. Instead of stalking them across social network profiles, I choose to send the two of them silent thanks–in whatever strange way one thanks their memories.