Back to Borrowing: Regaining a Love for the Library

When I was young, my mother would bring me to the library every two weeks. Under the watchful gaze of the librarians, I would pile up a stack of seven books (the limit I could take out at one time) from the small young adult section. It was a place of freedom and reading love. As a young girl, I knew the library hours by heart, and my library card was my most treasured possession.

I remember asking for books about geology, about Degas, and informing the librarian in clipped, precocious tones that I did not want a kids’ book but a “real one” about these topics. Their expressions never changed. They would simply walk me to the right section, show me where the books were that I might want, and leave me to flip through myself. They trusted me with the books, with whatever knowledge I would access. They knew that I was serious in my intentions.

It hurt when my visits started to break down. At the time, my hometown library was small and under-funded, a musty smelling room in the basement of town hall. It would flood at least once a year after bad storms. The sections were limited. At age 10 or so, I moved out of my young readers section and into Teen, seeking more reading material. Eventually my mother realized that I was diving into teen horror and romance, but she never said a hard no to my choices. Even so, we started visits to our local bookstore instead of the library. As sad as it was, I had literally outgrown my library—there were not enough new books on its shelves for me to read.

For a while, I held this against libraries. I still loved them in theory, and I would visit local libraries to find sources for my school papers, or to dig into YA series that I wasn’t sure I would like. But as a teen, I found myself thinking of libraries as something I did when I was a kid. Something I had outgrown, that couldn’t give me what I needed. Buying books, now that was joy—the books became mine forever, mine to take care of and write in and stack on my shelves. My love of the library melted away in the face of the glossy spines of bookstores and the broken spines of my home library.

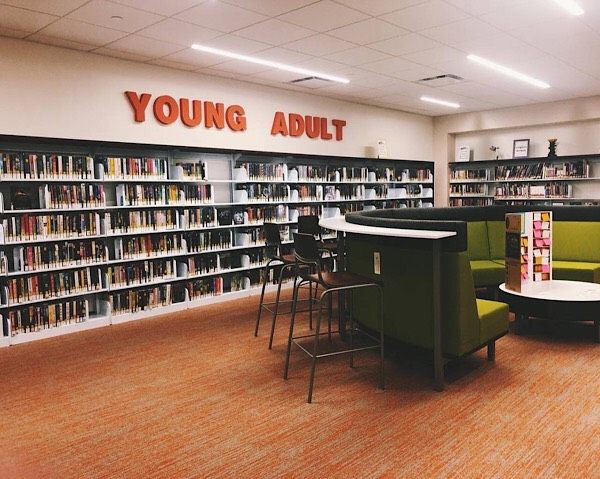

The Young Adult section of my now renovated and relocated hometown library.

But now, my hometown library has been moved to a new, beautiful location. Visiting it for the first time one winter break, it brought tears to my eyes, and it made me nostalgic. I went home to my apartment in Chicago and looked at my to-read shelf, stacked high. I thought about my attempts to be able to afford new releases; I thought about the disappointment of buying a book then finding it was a waste of my time, only to place it right into the Free Little Library a few days later. I thought about the joys of my childhood—discovering a new series and swallowing it in one bite, stumbling on authors I was able to try because the books were mine only for two weeks rather than for forever.

I held my library card in my hand, and chastised myself. Why did I not have a Chicago library card?

My plan for 2020 solidified. I would work down my to-read shelf to a reasonable level, and then I would go out and get a library card. I would find that same old joy again—the book-loving joy of a bookstore, except that with one simple swipe of a card, you get to take those books home for no cost at all. The joy of local librarians you can trust and the knowledge that you are supporting a crucial service to the community. I would support my own local library and help young readers in my neighborhood to never lose that joy.

And then came the shutdown of our city, necessary to hamper the spread of COVID-19. I wasn’t “ready” to get a library card in the way that I’d planned to—my to-read shelf is still a mess of books, smaller than when I made my goal, but still several book stacks deep.

But somehow the stagnation of staying at home has made me more impatient. I know how vital libraries are for so many, and I think of how many kids are at home wishing fervently for new books from their local, wrapped in careful plastic, crinkling in that satisfying, childhood sound that brings me so much nostalgia. Holed up with the many books I own, I find myself even more impatient to find a local library that I can call my own, where I can test out the waters of a new series or try out a new release or dig into poetry surrounded by bookshelves. I want to hold a Chicago library card in my hand, and feel that magical, bookish power spark in my palm.

When the shutdown ends in my state, the first thing I will do is visit my local breakfast spot. The second thing is to visit the lake. And the third thing will be to go to my local library. It’s past time I get my library card again.