Autism, By Way Of Nick Hornby

The road to compassion sometimes has an ugly start. Or at least not a beautiful one.

Definitely one of my favorite movies, in spite of its flaws. Definitely.

On a summer night when I was probably eight years old, it was too hot to sleep so we were all up past my bedtime hoping there was something good to watch on TBS. There was. It was called Rain Man, and it was unlike anything I had ever seen. I had never seen or heard the word autism before those two hours of edited-for-television traffic filled my screen with Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman and their fireball eight classic car and all those charming and tolerable meltdowns about Kmart or Wapner. And that gift hidden within Raymond Babbit, savant extraordinaire! His mathematical genius helps them score big in Vegas and kind of saves the day for his flawed but redeemable and “normal” brother. It filled my little heart with compassion (a feeling I didn’t have a name for that summer of 1991) like the air bladder of a goldfish, and suddenly a certainty that my future child would be autistic rose to the surface, too.

I had nothing to base this hunch on. Nothing. I navigated even then by blindly stretching out the arms of my intuition and feeling around. But that certainty just felt so sudden and so solid that I couldn’t shake it off.

I am happy to say that I’ve since acquainted myself somewhat more deeply with the pockets of empathy that came with my genes, but that one particular pocket still has that very particular sensation of pay attention to this, this feeling is here for a reason and that reason might be swaddled in your arms one day.

It’s a difficult thing to explain to people, and I am sure I’ve failed here to do it justice. Maybe it’s the limit of our language; before you can say turquoise you can only see blue, so until I either learn a better word or invent one, it’ll have to remain a vague combination of love and the desire to champion, help, and nurture.

Lots of our most important feelings defy explanation. It’s a problem I run into kind of a lot because I’m a sentimental fool by most accounts. Which is mislabeled trait that I hold as quite valuable; the language I speak most fluently is one of heightened emotion. And that’s probably why I fell in love with Rain Man. I wasn’t the only one.

It’s not a bad movie—it still makes my Top Twenty lists when people ask about art that helped shape me. But autism was a largely undiscovered country then, and Dustin Hoffman probably can’t be blamed for failing to hit the bulls eye. Even the folks hired on to consult on autism spectrum disorder didn’t know then what we know now, and what we know now is that there isn’t one, all-fitting autistic bulls eye to hit even if you wanted to. The target they tried to hit had to fit into the shape of a 1980s film narrative, which seemed at times obsessed with redemption. Does one need redemption from autism? Without a useful gift buried inside that insular world, is autism just a flaw? We know those answers now. We know better.

I forgive the film’s inaccuracies and I forgive you if you cannot, especially if you have parented through the innumerable and understandably less charming episodes of real world autism, which never pauses long enough for the actor playing your child to go to their trailer and wait for the next scene.

I am not eight years old anymore, and I don’t yet have any kids with or without autism. But that same feeling that it might be coming down the line has remained all these years later, and I have wanted to augment whatever compassion I came equipped with by being prepared. Just in case.

We know that rates of autism are rising fast, especially among boys. And I do hope to have children some day, so the odds aren’t as far fetched as once they might have seemed that I could be one of the many parents trying to figure out how to understand, anticipate, and adapt to the needs of a child who may not be able to articulate them.

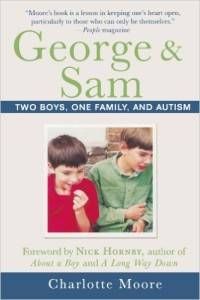

I find a lot of things by accident (arms outstretched, hoping they run into something good, remember) and this happens frequently in my reading life. While browsing my favorite bookstore one day, I picked up The Polysyllabic Spree, which is a collection of columns Nick Hornby wrote for The Believer. The premise of the column is simple: he wrote about all the books he bought each month and all the books he actually read each month. Spoiler: the numbers rarely broke even. If you are a reader of Book Riot (which you are), this column is probably your jam and you can probably appreciate how much I appreciated it, too. One can only find so many books to read by sheer, blind luck after all so a little help is nice. And with Nick Hornby’s help—he wrote a few other follow up volumes of similar essays—I found George & Sam.

Nick Hornby is also a parent of a child with autism. What he found in George & Sam was an incredibly fresh, honest, human, but admirable portrait of what it means to be such a parent.

Nick Hornby is also a parent of a child with autism. What he found in George & Sam was an incredibly fresh, honest, human, but admirable portrait of what it means to be such a parent.

Moore’s collection of essays centered around life with her two older sons (each of whom is on a different point of the autism spectrum) is both an incredibly illuminating read and an incredibly helpful resource—whatever Rain Man set moving in me, Charlotte Moore continued more fully. She writes from a place that’s probably not easy to get to—a place of having accepted her sons’ conditions, temperaments, comforts, needs, and triggers, which are each sometimes dynamic and sometimes unyielding. Her parenting style is one I would hope to emulate even with neurotypical kids. She is thoughtful and responsive, and if there is a whisper of resentment anywhere in the book, I could not find it. What one might imagine as a despairing, humorless job providing care for such a person can be balanced with moments of delight and even comedy. Charlotte Moore sometimes takes this delight in her sons, and at time laughs along, but never, ever in meanness of spirit.

Moore touches on her own early impression of autism, long before she was an adult and a mother. “I knew what autism was, or thought I did,” she writes. “In my teens I had been very struck by a book called For The Love Of Anne, the true story of an autistic girl who makes a rather miraculous ‘recovery,’ largely…through interaction with the family dog.” Ah yes, autism—that curable, redeemable condition that traps a normal person inside an abnormality. That old story.

Her commentary on things she has learned since then is also illuminating. In one chapter regarding the singular focus some autists possess toward a subject and the fervor in which they strive to become experts on it regardless of tedium, she writes “female readers who have sat through dinner parties smiling politely while their male companions hold forth may protest this is not an exclusively autistic characteristic…indeed, researchers…have suggested that autism may be a form of extreme maleness.” Point taken.

Like every parent facing the new challenge of autism, she also read a lot of books about it. And like many of those parents, they sometimes did more harm than good, sometimes leaving her with an overwhelming sense of inadequacy. The final pages of George & Sam, however, are filled with a list of resources she found to be quite helpful. And there are many.

Does she struggle to keep up at times with the boys? Does she recount moments of exhaustion? Is she at times baffled at inexplicable changes in her sons’ social behavior? She does. She is. “I can’t think of any aspect of daily living that hasn’t been encroached upon by autism in some way, at some time,” she writes.

But through it all, one brief string of words struck me like lightning: “one of the things I love about autism,” she says at one point. That, my friends, is the power of sentimentality in the best possible sense. She loves her boys, who she often describes as “autistic through and through,” and she loves them completely. Complete love, through and through. That’s the ticket.

I don’t know if one day someone on the autism spectrum will call me dad. If yes, then I will have this book at the ready, with its observation and its cheer that lacks any false promise of ease. If no, I am sure I will know others starting down their own road to compassionate parenting, and I will have this book at the ready for them. Moore’s parting advice is that “the sooner you get to work on intervening between the child and the rigidities…the better, but it’s comforting to know that if you haven’t achieved this, you haven’t missed the boat—or rather, you may have missed that boat, but there’ll be another one along in a while.”

The hope for compassion is sometimes more helpful than the hope for a cure.