A Brief History of the Library of Congress

Today, the Library of Congress holds over 25 million cataloged books, has items in 470 languages, and is home to the papers of 23 presidents, a cuneiform tablet, and a Gutenberg Bible. The Library receives an average of around 20,000 items a day, about 10,000 of which are added to the permanent collection and occupy three buildings at its main campus in Washington, D.C. It also has storage facilities in Maryland and a conservation site in Culpepper, Virginia housed in an old Federal Reserve storage center and Cold War bunker. But the Library as an institution has lived through many different locations, starting with an initial, small collection that was created when the U.S. federal government first moved to Washington, D.C.

The Library of Congress began its story in the still-under-construction Capitol building after Congress received approval from President John Adams and passed an order on April 24, 1800, that dictated that books should be kept in “a suitable apartment” within the Congressional building. Originally intended as a reference library of sorts for Congress members and their staffs, the library had a budget of approximately $5,000 that was used to order a collection of around 700 books, plus maps, mainly from booksellers in London.

When Thomas Jefferson was elected president, he expanded the powers and reach of the library by extending borrowing privileges to the president and vice president and giving the president the power to appoint a Librarian of Congress as well as establish a joint committee to oversee the library’s operation. Continuing the formalization of the Library of Congress as an institution, in the early 1800s, the library published its first catalog, which had entries for 3,076 volumes, and 53 maps, charts, and plans. The same year, members of Congress were exempted from paying overdue fees on library materials.

Just over a decade after Jefferson’s actions to expand and formalize the library, British forces descended on Washington in August of 1814 in retaliation for the capture of York. During their occupation of the capital city, British troops burned the U.S. Capitol, destroying almost all of the library holdings that had existed during the first decade of its history. The only confirmed surviving item from the pre-1814 library is an 1810 federal government account ledger that was taken by British Rear Admiral George Cockburn, who brought the book home with him as a spoil from the ransacking of Washington. Inside the book is written, “Taken in President’s room in the Capitol, at the destruction of that building by the British, on the Capture of Washington 24th August 1814 by Admiral Cockburn.” The ledger remained with Cockburn family members for over a century until it was bought by rare books collector Abraham Simon Wolf Rosenbach, who gifted it back to the Library in 1940. Today, the ledger, as well as other books that survived the fires of 1814 but whose original storage location is unknown, are housed in the Library’s Rare Book Reading Room.

After the original connection burned, Jefferson, who had continued to be a passionate advocate for expanding the Library’s holdings, offered to sell his personal collection of books to the government for the Library of Congress. Jefferson had long been a passionate reader and collector of books since the Colonial Era. His personal library at Monticello was, at the time, the largest private collection of books in the United States. Having previously lost parts of his own collection to fire in the 1770s, Jefferson had put large amounts of time and financial resources into cultivating his library and organized it using a modified classification system from British libraries. Motivated by both his belief in the importance of a strong collection for congressional reference purposes and his financial woes, Jefferson negotiated a sale of 6,487 volumes to the United States for $23,950. These volumes, along with additional purchases and donations, formed the new “core collection” of the library as it approached the half-century mark of its founding.

On December 24, 1851, the Library faced yet another crisis when a fire ripped through the collection, destroying two-thirds of the collection and two-thirds of the books that were a part of Jefferson’s original transfer. While Congress did authorize funds to replace materials that had been lost, there was no money appropriated for new additions to the collection, and the fire of 1851 became symbolic of the overall conservative approach of John Silva Meehan, the Librarian of Congress from 1829-1861.

Meehan and the congress members who collaborated with him believed that the purpose of the Library of Congress should be limited to only providing the books and other materials that Congress needed regular access to in order to fulfill their role in government. In contrast to today’s expansive and public Library of Congress, Meehan envisioned a limited collection that was restricted to those working in the legislative, and occasionally executive, branches and not one that collected or cataloged a more extensive archive of materials relevant to America as a nation. At the same time, leaders of the growing Smithsonian Institution were pushing to designate it, not the Library of Congress, as the National Library of the United States.

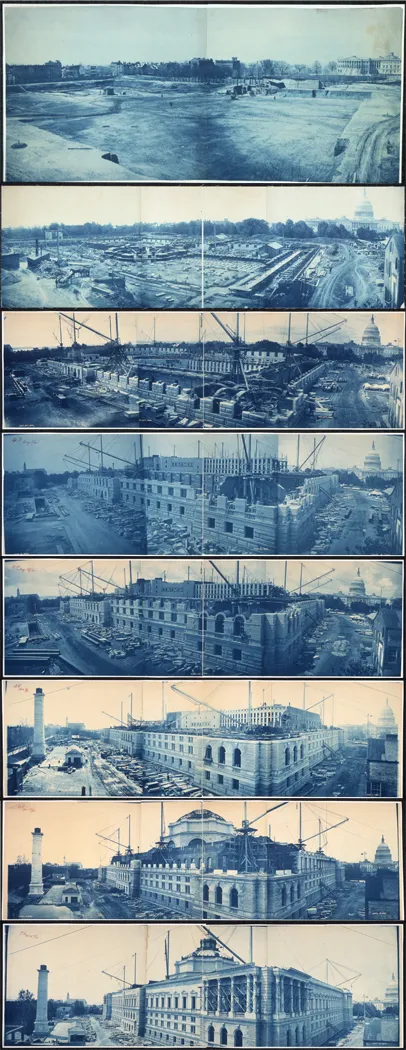

Unfortunately, the Smithsonian’s holdings were also affected by fires during the later half of the 19th century, an event which strengthened the case for the national archives role of the Library of Congress, especially after it began planning a move to a new building (now called the Thomas Jefferson building), which was being specifically designed to lower the risk of fires. In 1866, Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry agreed to move the 40,000 non-scientific volumes in the Institution’s library to the Library of Congress’s new building once it was completed.

If the move to the Thomas Jefferson building was one major sign that the Library of Congress was moving into a new phase of expansion, the other was the appointment in 1861 of Ainsworth Rand Spofford as the Librarian of Congress’ assistant. Spofford, who would take over the librarian job in 1865, was hired by President Lincoln’s choice to lead the Library, John G. Stephenson. As Stephenson also served as a physician in the Union Army, he was often away fighting in the Civil War, leaving the practical operations of the Library to Spofford.

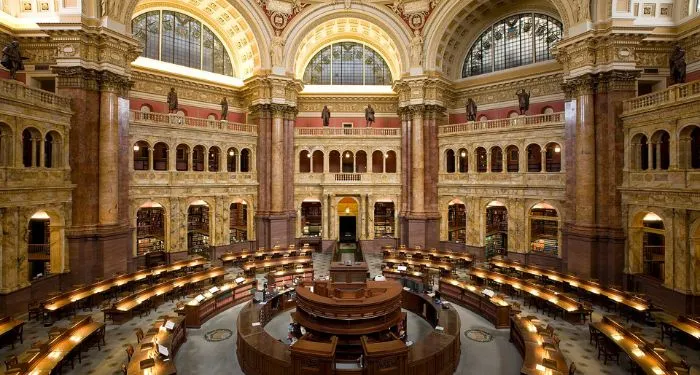

In 1865, Spofford became the Librarian of Congress, and the increased federal spending of the post-war years, as well as the bipartisan support Spofford built in Congress, led to several key developments in the Library of Congress’ transition from Congressional reference to the national library. Between 1865 and 1870, Congress appropriated funds for the new building, made the library the official center of control for copyright registration and deposits, and continued to expand its collections. In 1897, when the Library moved to its new home in what is now the Thomas Jefferson Building, its catalog contained over 800,000 items, and its staff had doubled in number. As the 20th century approached, the Library of Congress continued to establish its position as the national library and as an important holder of archival and historical collections, as well as government reference materials.

The years between the Library of Congress’ move to a new building and World War II saw continued growth and significant acquisitions, particularly in the Library’s collection of items purchased internationally. Thanks to the diplomatic skills of Librarians of Congress John Russell Young and Herbert Putnam, the Library put an increased focus on acquiring valuable items from other nations. Some of the most significant acquisitions included 2,600 volumes from the library of the Romanov family, large quantities of books in Chinese, Japanese, and Hebrew, and a Gutenberg Bible. Putnam also worked to promote the role of the Library of Congress as the foremost place of primary source research related to the history of the United States, a philosophy that helped persuade President Theodore Roosevelt to transfer the papers of the Founding Fathers to the Library’s collection from the State Department.

This period of time also saw the establishment of the Legislative Reference Service (today the Congressional Research Service), the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled, and the approval of the plans to build an annex to house the growing collection, which today is known as the John Adams Building. Private donations from major philanthropists of the time also expanded the library’s role in promoting arts and culture, with donations being used to offer concerts and establish and fund roles like that of the United States Poet Laureate.

The year 1939 marked a time of change for both the world, much of which was already embroiled in the Second World War, and the Library of Congress, where the retiring Putnam was replaced by FDR appointee Archibald MacLeish. MacLeish, who helmed the Library of Congress through the war years, placed an increasing emphasis on the Library of Congress as a stalwart against the forces of totalitarianism and a protector of free and democratic access to information. One of the best known Librarians of Congress, MacLeish (who would resign in 1944 to become Assistant Secretary of State) saw his position as a political role and crucial to the war effort, and during his time, he oversaw programs from clandestine information gathering on behalf of the Allies to the safe storage of valuable, historic documents at Fort Knox.

Post-war, MacLeish’s successors continued to advance the Library’s commitment to information access and looked to other nations as a way to expand the international collections. In the 1950s, Library of Congress Missions were created across the world for a variety of purposes, including assisting the beginnings of the United Nations, establishing the National Japanese Library, and acquiring items from the war-ravaged libraries of Europe to bring back to the United States. The Library of Congress also established additional collection centers overseas, including in Cairo and New Delhi.

In the later half of the 20th century, the library had grown its holdings, its physical footprint, and its outreach, and recommitted to and expanded on the research services that it offered to Congress. Library leaders and staff also began to explore how to make the collections accessible beyond the library’s walls, by harnessing burgeoning digital technologies that could allow users to view even rare and delicate items from the comfort of their own homes. In 1981, the library officially stopped filing cards in the main collection and began online cataloging of its collection, marking the end of an era in its acquisition and organizing processes.

In June 1994, the Library debuted its website at the American Library Association’s annual conference, and in October of the same year, the National Digital Library program, which works to digitize primary sources related to the study of American history, began. These online outreach efforts were part of a larger expansion and opening, which was echoed by the opening of the James Madison Memorial Building to the public in 1980 and the Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation in 2007. The library also worked with First Lady Laura Bush to host the first National Book Festival in 2001, bringing authors, researchers, and readers together in the nation’s capital.

As the library has continued to grow in the 21st century, it has expanded both its physical holdings and its national impact in a variety of ways. The library collaborates with international research centers, runs a website for American citizens to access Congressional information, collects the stories of veterans, has an app to expand access to books for readers with visual impairments, and has introduced new literary prizes for American authors and musicians. In 2016, Carla Hayden became the first woman and first African American to serve as the Librarian of Congress, and during her tenure, the Library’s collection has expanded to over 162 million items.