Lauren Beukes On Writers and Their Cats

This is a guest post from Lauren Beukes. Lauren is a former journalist who got to interview homeless sex workers, electricity cable thieves, and township vigilantes among other interesting people, before she turned to writing kids cartoons and full-time novel-writing. Her books include Zoo City, Broken Monsters, and The Shining Girls and have been translated into 26 languages and won multiple awards, including the Arthur C Clarke Award, the University of Johannesburg Prize, The Strand Critics Choice Award, and the August Derleth Prize. She lives in Cape Town, South Africa, with her daughter. Follow her on Twitter @laurenbeukes.

I normally wake up at five am, not from any writerly duty, to use that magic quiet time to steal some words before I have to get my daughter ready for school, although I should, but because our kitten, Sage, jumps onto the bed and starts frantically purring and padding and nipping at my fingers to let me know she was out adventuring but now she’s back and shouldn’t I stroke her and make a fuss and feed her. But this Monday I woke without her to ominous quiet.

I’ve had several writer cats over the years. Smoky, my half-Siamese, half-Persian grey, watched me writing stories in long hand from the time my five year old tiny mind was blown when I discovered that writing was a job you could have, Like, you actually get paid to make up stories! For a living! I’ve never wanted to be anything else since then, although it took me 20 years before I published my first short story.

But Smoky was there when I was 17 and writing my first novel, an epic fantasy about tricksy demons and a cursed heroine, lending furry moral support, while I cracked out 60,000 words two-finger typing in Word Press on my Pentium 1. (That novel is going to remain in a drawer where it belongs, to the end of time, and will be burned on my death, as it deserves, thanks for asking). She died of old age in Johannesburg.

In 1999, living in Cape Town, I got a black kitten with a white star on his chest from a friend. I named him Mir, because the space station was in the news at the time, a bright glint in the darkness. Shortly afterwards, I moved to New York for love, and then to Chicago to get over the heartbreak and left Mir with my dad. When my aunt asked him about the name, my dad, always the raconteur, told her an elaborate story about Mir being literally a space cat – that the Russian space agency had devised a fund-raising endeavour to fertilize cat eggs in space and sell off the space kittens for $250,000 each, but because I did the PR for them, they paid me with the runt of the litter. She believed it for months.

Mir

Mir was a huge tom, who sometimes got mistaken for a dog at first glance, full of grump and charisma. When I came back, he sulked for days, refusing to let me touch him. He’d sit on my desk and idly bat any loose objects on to the floor, while I was writing my first book, a non-fiction pop-history, Maverick: Extraordinary Women From South Africa’s Past. If he claimed my chair, he’d defend it with tooth and claw and the only way to get him to relinquish it was by spinning it round and round til he got dizzy and jumped off.

When Mir went missing one night, we put up posters all around the neighborhood offering a reward and advertised in the local paper. We had a pet psychic phone us to say she knew he was alive and would be coming back soon, which was plausible, seeing the last time he’d gone missing we’d found him at a neighbour’s down the road, luxuriating in front of the fire being fed roast chicken.

A day after he was missing, a man with a limp and twitching speech, clutching the reward poster, rang the doorbell to say he’d seen a boy bury our cat in the field. I thanked him, but said I’d need proof. Could he show me? But he was struggling to communicate and I thought he was making it up.

By the end of the week, I was desperate. I walked down the road, knocking on every door to ask, and seven doors down, a young Dutch guy answered, and said, why yes, he had seen my cat. He went for his daily morning walk with his cup of coffee and his dog and he found Mir dead on the side of the road, obviously hit by a car. And he doesn’t like cats and he thinks black cats are bad luck, but he couldn’t stand to see a dead animal lying there, so he went back home and got a black plastic bag and a spade and carried his body to the field where the African immigrants come to play soccer in the afternoon. And he buried him under a tree, so he would have shade, with a view of the sea, and near the highway, so he wouldn’t be lonely. I wept at his thoughtfulness and for our big mean tom who was so loved.

Nikita and our ginger tom, Sputnik, aka Boy, saw me through Moxyland and Zoo City and The Shining Girls and the birth of our daughter, Keitu in 2008. When Boy nuzzled Keitu for the first time, she broke out in a rash, but he never bit or scratched her, even though her favourite move was collapsing on top of him.

Boy

Boy used to sit on my desk, curled up next to my laptop while I wrote late into the night, terrified of my success and the pressure of winning awards, of getting a big book deal, and trying to write to live up to the most evil high expectations – my own. He was never overly affectionate, but he’d keep me company in the lonely hours of writing, when I was stuck in my head with imaginary people.

I got divorced in 2014 and the cats stayed with my ex in the home they knew. Boy died of cancer last year and when my daughter, now seven, is having sad or complicated feelings, she goes to: “missing Boy” as her way of explaining how she feels. She says his ghost walks with her and keeps her safe.

Ivy

I got a new kitten, Ivy, a calico with weird face-markings. My friend Dale Halvorsen, aka award-winning cover designer Joey Hi-Fi (who has done all my South African covers, which are closest to the souls of my books) describes the way they make her look as a “burn victim Ewok.”

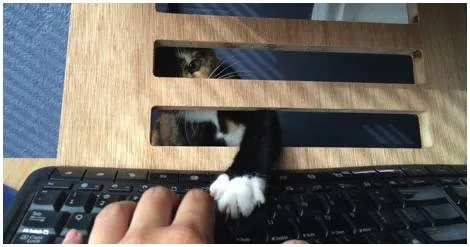

When Dale and I started writing our horror comic, Survivor’s Club, together, we elected Ivy as our third co-writer. We’d hold up pieces of paper with two plot options on them and let her paw the one she thought was the better choice. She’d climb Dale’s leg like a tree, clawing her way up his jeans and would bat at my fingers while I was typing.

But Ivy was lonely and bored, so in November last year we went to a rescue organization called Raise ‘n’ Rescue and Keitu picked out a tiny black and white little girl kitten called Sage to come home with us.

Sage

Sage was precocious and fearless. She rugby-tackled Ivy and chewed on her head, climbed everything climbable and made great leaps off tables and window sills and down the staircase. She insisted on sitting on our laps while we were writing, but her favourite thing was chasing cockroaches. This made her an even better writer cat than normal, because as you probably know, writers are very fond of snacks. And snacks produce crumbs and crumbs, well, crumbs attract roaches, although I’d never seen one until the great huntress Sage started dragging them out of the dark crannies they hid in and into the dining room where I work during the day, so she could chase them around, while I lifted my feet off the floor and yelped “Just kill it, already!”

All past tense.

Because Sage didn’t come home at all. My housemate said she’d heard a terrible ruckus from the dogs in the house behind us at 3am. Worse than usual.

Full of dread, I went down the road, calling for Sage, listening for her little raspy meow, the jangle of the tag on her collar, and ringing all the other door bells on the way to ask, just in case.

“Jesus Is Lord” it proclaimed in the window of the squat 1930s house painted a fleshy pink, tucked away behind the black wrought iron fence. I rang the intercom and after a minute, a woman peered out from the lace curtains, “Yes, can I help you?” she said, warily.

“My kitten is missing, we heard your dogs barking at 3am, maybe…”

“Just a minute. I’ll go see.”

She took so long to come back I thought, I hoped, she’d forgotten about me. Gone to check, nope, nothing there, and got distracted by daytime television or something.

I was about to ring the doorbell again, when she emerged from the side of the house, carrying a little body wrapped in a white blanket, a black and white paw sticking out stiffly in front.

She was crying, “I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry. I feel terrible. What can I do? I can’t bring her back, but I feel so bad, what can I do, please tell me?”

She passed me that small stiff package through the fence. “There’s nothing. Please. Thank you.” I said, numbly. “Thank you.”

I carried Sage home, holding her against my chest to fumble with the keys to open the door. I sat on the kitchen floor and unwrapped the blanket to see her cold and rigid, her life fled away. She was covered in grass, her fur plastered with mud. There was no blood, no bite marks. They must have thrown her and broken her neck or snapped her spine.

At least, I thought, a thousand at leasts: at least it was probably quick, at least they didn’t rip her apart, we heard the barking, so I was able to find her today, at least we know what happened, at least we can bury her.

But all the at leasts weren’t as comforting as I thought they’d be. I sat next to her on the kitchen floor and sobbed and sobbed and then I washed the body with a wet cloth, stroking the mud out of her fur, one side, then the other.

Love is blow-drying your dead cat so she’ll look okay when your seven year old comes home, so she can say goodbye. Love is the friends who come round to sit with you while you do it and hold your hand.

The rigor mortis wore off by the time Keitu came home from school, so she was able to hold Sage’s body, wrapped in the blanket, in her lap, sobbing.

She wrote Sage a letter: “I love you so so so so so so so so so so so so so so so much. I miss you so so so so so so so so so much I could die. I hope you find ghost cockroaches to chase in heaven. I hop you find the soul of Boy and Mir so you can play with them and pouns on them.”

We buried Sage in our garden, in a grave strewn with rose petals, with her favourite toy and a little bit of food and water and a treat, for the afterlife, and a prayer to Bast, the Egyptian Cat Goddess to guide her there. We planted sage over her grave so she could give life to something growing.

And we told stories about her and what she meant to us, because that’s all we really have in life, the stories we tell about ourselves that stay behind, and the pets that share in them, and for writers, that keep us company in the lonely telling of them.

- The Women in Science We Don’t Write About

- Terry Tempest Williams on Women and Books

- Feminist-Friendly Comic Books

- Fatima Mernissi, Morocco’s Feminist Icon

- Sonali Dev on Why She Writes The Heroines She Writes

- All Around the World: Women Writers from Every Continent

- On Worldviews and Reading Widely

- 50 of the Best Heroines from Middle Grade Books

- Between Worlds: Finding Home in Fantasy