The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh: Free to The People

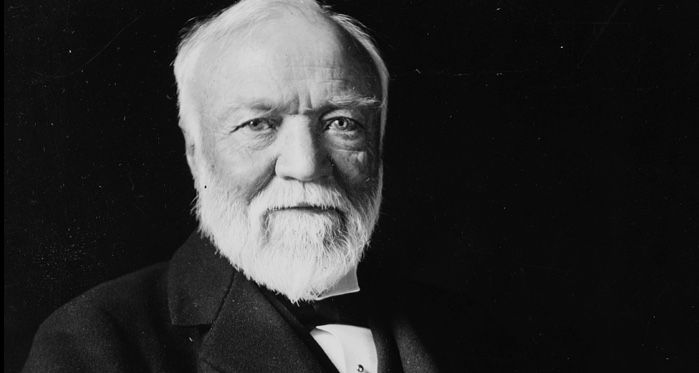

The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh turns 125 this year, which makes it one of the oldest free public library systems in the country. And, in fact, internationally: within his lifetime, rags-to-riches steel magnate Andrew Carnegie founded 2,500 free, public libraries all over the world. I know, right? Even capitalists do something neat every so often.

Why was this one so focused on libraries?

Legend has it when a 17-year-old Carnegie was working as a bobbin boy at a textile factory in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, he decided to join the local library in an effort to better himself. Like most public libraries at the time, the Allegheny Public library charged a subscription fee, and $2 was an astronomical sum to an immigrant laborer in 1852; buying books was even more expensive, which left the aspiring self-educator in a bind. He attempted to convince the library’s administrator to waive the fee but the man refused. Carnegie, not one to be denied, then or ever, went with the time-tested route of writing a letter to the editor of the city paper; and lo, suddenly the library was open to all working men.

His self-improvement method also seems to have been on the nose: Carnegie went from bobbin boy to an entrepreneur with an estate worth $350 million (about $7 billion in today-money).

Feel free to quote that statistic to anyone who asks you why you always have your face in a book.

Carnegie donated all of his money before he died because, as he is said to have proclaimed, “A man who dies rich dies in disgrace.” The people had built his empire and he believed it was his duty to to contribute back to the community that had allowed him to live well. One of the ways he chose to do so was by giving them what he had been denied: free access to libraries.

His philosophy on learning, however, was not of the, “giving people a fish,” variety. It was of the, “teaching people to fish,” variety. Seed money for a start up, if you will. He had made his own way and those who were to benefit from his largesse were gong to have to do the same. “Take these books,” he offered. “It’s not safe to go alone.” Then he locked the door behind you, made sure the angry ogres were posted on both sides of it, and activated the runes.

Fair enough. 2,500 libraries is a lot of resources.

How did the the Carnegie of Pittsburgh Library system, that hosts almost 4 million visitors a year, come into being?

In November of 1880, Carnegie wrote a letter to the city’s mayor offering $250,000 to fund six libraries, a main branch and five satellite branches, provided that the libraries were free to use and that the city donated the land and maintained the libraries after the initial outlay. The city initially rejected the proposal but changed their minds when Carnegie upped his donation to $1 million, though he did then require the city to pledge $40,000 for ongoing support.

The idea was quite popular: the six initial branches opened between 1898 and 1900, and a seventh in 1905. From the beginning, librarians held storytimes, reading clubs, and clubs. Carnegie was so pleased with the progress that despite his agreement with the city, he bought the land for the eighth branch himself and donated it (that one is extra fancy and has a music venue integrated into the building). The system now boasts 19 branches, each building tailored to meet the aesthetic and needs of the community it resides in and each offering far more than just books: there are storytimes for kids of various age groups, book groups, language classes, teen meetings, homework help sessions, holiday events, writing workshops, cookbook clubs, resume workshops, citizenship classes, translation services, and just…the absolute best spaces to work in the whole city. I think that last is the thing I’ve missed most during the pandemic. Walking in to the Main branch, grabbing coffee, finding a spot on the couch, and being around books and people who love books and taking breaks to say hi to the embarrassing number of librarians who know me by name. And know to ask me how my writing is going.

And I’m definitely not the only one. In 2011, a referendum to increase taxes passed by 72% because $3 million of the funds raised per year were going to library. That a whole city’s worth of people willing to chip in for books, computers, and the giant trademark name building blocks in the giant, bright, sunny, absolutely packed full kid’s room.

So, maybe not entirely free to the people. But close enough for rock and roll. And all the books about rock and roll. And everything else for that matter.

Oh, and if you go up into the stacks on the third floor (or higher) and sit in the windows seats, you can look out over the Carnegie Museum of Natural History dinosaur hall while you read. Turns out he liked science, too.