When a Book is Almost Too Pretty to Read

My husband and I were hardcore Lost fans. So when we heard about S., the novel co-authored by J.J. Abrams and Doug Dorst, designed to look like a well-worn library book—its pages inscribed with communications between the two main characters and packed with ephemera which can be removed from the pages and read like found objects—of course we had to buy it. A first edition, published and purchased in 2013. It came in slipcase with a paper seal that you break to remove the book. That seal was our downfall. Neither of us has ever opened it.

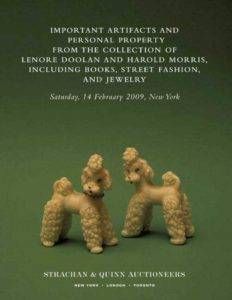

This isn’t the first time I’ve experienced this kind of intimidation in relation to a book. Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry by Leanne Shapton is the catalog for a fictitious auction. Filled with pictures and descriptions of the different lots of items, it tells the story of a couple’s relationship through their possessions. Paperback binding, because it’s meant to mimic an auction catalog, it feels a bit flimsy. One of my favorite books, I constantly read and re-read it…but oh so carefully.

This isn’t the first time I’ve experienced this kind of intimidation in relation to a book. Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry by Leanne Shapton is the catalog for a fictitious auction. Filled with pictures and descriptions of the different lots of items, it tells the story of a couple’s relationship through their possessions. Paperback binding, because it’s meant to mimic an auction catalog, it feels a bit flimsy. One of my favorite books, I constantly read and re-read it…but oh so carefully.

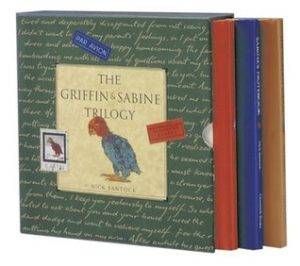

The Griffin & Sabine Trilogy by Nick Bantock is/was, I suppose, an early precursor to S. Two artists exchange letters. Beautifully illustrated (the illustrations are supposed to be the work of the two main characters) readers get to remove the letters from the envelopes to read them. As we get to know these two people we are meant to doubt the existence of Sabine. Is she a figment of Griffin’s imagination? A mystery develops. Secondary characters are introduced. The trilogy outgrew itself and a second trilogy followed, the last book of which is out this year. These books, fortunately, still feel mass-produced and so I’ve no hesitancy when reading them.

The Griffin & Sabine Trilogy by Nick Bantock is/was, I suppose, an early precursor to S. Two artists exchange letters. Beautifully illustrated (the illustrations are supposed to be the work of the two main characters) readers get to remove the letters from the envelopes to read them. As we get to know these two people we are meant to doubt the existence of Sabine. Is she a figment of Griffin’s imagination? A mystery develops. Secondary characters are introduced. The trilogy outgrew itself and a second trilogy followed, the last book of which is out this year. These books, fortunately, still feel mass-produced and so I’ve no hesitancy when reading them.

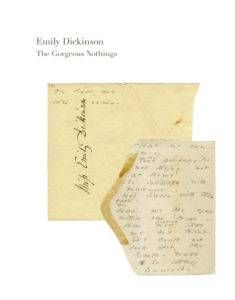

Sometimes it’s not necessary to remove the letters from the envelopes. Two volumes of full-color facsimiles of Emily Dickinson’s original poems on the recycled scraps of household paper she favored, Envelope Poems and The Gorgeous Nothings reproduces the experience I imagine Dickinson’s sister had upon discovering the work in a desk drawer. The odd shapes of the papers combined with the hieroglyphics of the poet’s writing turns the manuscripts into something you expect to see hanging on a gallery wall. The result is beautiful.

Sometimes it’s not necessary to remove the letters from the envelopes. Two volumes of full-color facsimiles of Emily Dickinson’s original poems on the recycled scraps of household paper she favored, Envelope Poems and The Gorgeous Nothings reproduces the experience I imagine Dickinson’s sister had upon discovering the work in a desk drawer. The odd shapes of the papers combined with the hieroglyphics of the poet’s writing turns the manuscripts into something you expect to see hanging on a gallery wall. The result is beautiful.

What do you call this category of books? Novelty implies there’s a gimmick involved, when in fact you could argue the exact opposite is the case. The act of reading is elevated to an experience that can not be duplicated digitally because the author (usually with the help of a designer) has included another component to create immersive content which relies on more than words on a page. The physical book as an object becomes an essential part of the storytelling process.

The brilliant Margaret Wise Brown, best known for Goodnight Moon, also wrote a book called Little Fur Family. The original editions were covered in rabbit fur because she thought it would be attractive and comforting to children. Unfortunately, the books were also attractive to moths. Few have survived, making those that are still around very valuable. First editions, with the fur dust jacket and the original box, can sell for over a thousand dollars. Fortunately for children the newer Little Fur Family board books sell for under $10 and incorporate faux fur.

Therein lies the conundrum. These types of books can be expensive to produce and tricky to preserve, and so there’s the fear that they are just too pretty to read. You don’t want to get them dirty. It’s the same instinct that induces some people to remove the dust jacket from hardcovers—an irrational need to protect a thing whose original purpose was to protect the book. Books are not sacred; their purpose is utilitarian. They are containers for words and ideas. But there are books that we are also meant to enjoy and appreciate as art objects. The challenge is to find a balance. To not be intimidated into treating these books as more precious or more fragile than traditional books. To not be afraid to enjoy them.

E-readers are sooo much less complicated.