WORD WEALTH: My Best Friend and Nemesis

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Junior year of high school, my English teacher had A Reputation. I knew this going in. Not only did I know it because of my peers, I knew it because my uncle had had the teacher when he was in school and, as he told me, he Found Himself In Trouble A Lot.

This particular teacher had a knack for assignments that were unbearably difficult. I remember a five-page essay on The Red Badge of Courage in which we were not allowed to use the word “that” once. For each use, our letter grade would drop. I remember near the second half of the year having grades knocked for not including sentence fragments in our writing (for style!) and for daring to repeat a word within the same page.

Then there was the assignment where we could not use a single. Latinate. Word.

We had an assignment every quarter, too, that required memorizing a piece of literature and performing it in front of our classmates. This wasn’t simple recitation. This was a performance. We had to go up there and give our all. Standing still, awkward shuffling, hiding our hands — all of those things were points off our grades. We learned to memorize through walks: walks outside, walks around the hallway, walks through the field house. We took what we were working on memorizing for these trips in order to think about literature in a different way.

But the true enemy in that class was a book.

And that book was Word Wealth.

Ward S. Miller wrote the 1939 classic, which found itself in classrooms everywhere. But in my school, our class was one of the only few to still be using it in the early ’00s. Other classrooms and teachers had moved on to far fancier vocabulary programs and exercises. But my teacher, the strict and hardass educator that he was, chose to stick with the book that we all loved to hate.

And the book everyone hated to love.

Word Wealth, in my English class, meant that each week, we were responsible for learning a selection of new vocabulary words. But more than mere new words to learn, Word Wealth required learning etymology, or the origin of words. We learned prefixes. We learned suffixes. We learned root words.

It’s because of Word Wealth that I fell deeply in love with Latin.

Junior year of high school is, perhaps, the hardest year in a high schooler’s career. It’s that pivotal year that requires so much. It was, for me, a year that meant crying over earning a B on a psychology exam and having my teacher — who was one of the most important ones in my life — give me the kind of encouragement about grades, about the future, and about how I knew far more than any test could ever measure and that mattered. It was the year I decided that I was throwing out all of what I thought I wanted in my college future (Michigan State or bust) out the window because a friend told me about this really weird hippie school in rural Iowa that didn’t teach on a traditional semester plan. It was the year I was part of an “honors physical education” program, which without context, sounds absolutely bizarre. But in practice, was one of the best leadership experiences I could have in high school.

It was the year I walked away from my favorite school activity because my coach was a sexist asshole.

Friday mornings were Word Wealth test mornings. A week’s worth of studying would culminate in one of the few English exams that made sense. You’d either know what the word meant or you didn’t. You weren’t tested on your ability to not use the word “that” or how few adjectives you used in a paper. Instead, you demonstrated the knowledge of what “bi” meant. What “ap” meant. What “pan” meant. What “pnea” and “uous” and “ure” mean.

Learning those was, of course, an exercise in precision. But it was an exercise in precision that led me to seeking out learning more about how language works and functions, which led me to taking Latin for many classes in my hippie college.

Which helped me learn how to be a strong, effective writer.

I have a solid base of what language means and how it’s used. At the time, of course, I didn’t understand how knowing those words or parts of words would make a difference in my life. I didn’t understand, either, how writing a paper without Latinate diction would matter. Naturally, though, my teacher’s agenda came through — you learn what the Latin is and uncouple it from your writing when you can choose another way to say something. When you can maybe be more precise.

There are times, still, as an adult, when I get the cold sweats thinking about another Word Wealth test. I’ll have a nightmare that I forgot to make my flashcards or study. That this will be the test that means I’m a failure and I flunk out of the hardest high school class. I don’t think it happened, not even once, during high school. But the nightmares still pop up every once in a while.

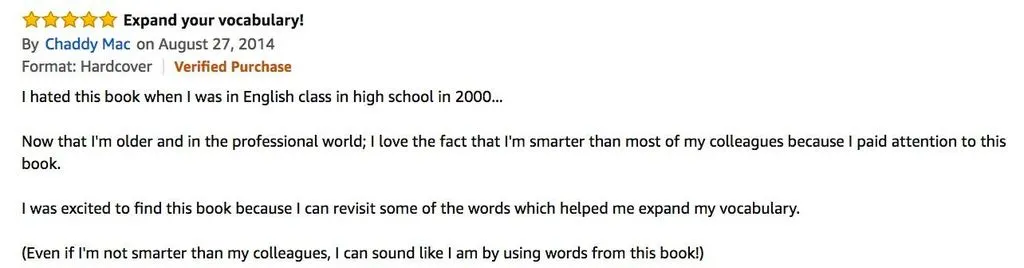

And then there are times when I can toggle over to the reviews of Word Wealth on Amazon and see that these feelings are common among others who experienced this particular textbook in school:

Junior year of high school, my English teacher had A Reputation. I knew this going in. Not only did I know it because of my peers, I knew it because my uncle had had the teacher when he was in school and, as he told me, he Found Himself In Trouble A Lot.

This particular teacher had a knack for assignments that were unbearably difficult. I remember a five-page essay on The Red Badge of Courage in which we were not allowed to use the word “that” once. For each use, our letter grade would drop. I remember near the second half of the year having grades knocked for not including sentence fragments in our writing (for style!) and for daring to repeat a word within the same page.

Then there was the assignment where we could not use a single. Latinate. Word.

We had an assignment every quarter, too, that required memorizing a piece of literature and performing it in front of our classmates. This wasn’t simple recitation. This was a performance. We had to go up there and give our all. Standing still, awkward shuffling, hiding our hands — all of those things were points off our grades. We learned to memorize through walks: walks outside, walks around the hallway, walks through the field house. We took what we were working on memorizing for these trips in order to think about literature in a different way.

But the true enemy in that class was a book.

And that book was Word Wealth.

Ward S. Miller wrote the 1939 classic, which found itself in classrooms everywhere. But in my school, our class was one of the only few to still be using it in the early ’00s. Other classrooms and teachers had moved on to far fancier vocabulary programs and exercises. But my teacher, the strict and hardass educator that he was, chose to stick with the book that we all loved to hate.

And the book everyone hated to love.

Word Wealth, in my English class, meant that each week, we were responsible for learning a selection of new vocabulary words. But more than mere new words to learn, Word Wealth required learning etymology, or the origin of words. We learned prefixes. We learned suffixes. We learned root words.

It’s because of Word Wealth that I fell deeply in love with Latin.

Junior year of high school is, perhaps, the hardest year in a high schooler’s career. It’s that pivotal year that requires so much. It was, for me, a year that meant crying over earning a B on a psychology exam and having my teacher — who was one of the most important ones in my life — give me the kind of encouragement about grades, about the future, and about how I knew far more than any test could ever measure and that mattered. It was the year I decided that I was throwing out all of what I thought I wanted in my college future (Michigan State or bust) out the window because a friend told me about this really weird hippie school in rural Iowa that didn’t teach on a traditional semester plan. It was the year I was part of an “honors physical education” program, which without context, sounds absolutely bizarre. But in practice, was one of the best leadership experiences I could have in high school.

It was the year I walked away from my favorite school activity because my coach was a sexist asshole.

Friday mornings were Word Wealth test mornings. A week’s worth of studying would culminate in one of the few English exams that made sense. You’d either know what the word meant or you didn’t. You weren’t tested on your ability to not use the word “that” or how few adjectives you used in a paper. Instead, you demonstrated the knowledge of what “bi” meant. What “ap” meant. What “pan” meant. What “pnea” and “uous” and “ure” mean.

Learning those was, of course, an exercise in precision. But it was an exercise in precision that led me to seeking out learning more about how language works and functions, which led me to taking Latin for many classes in my hippie college.

Which helped me learn how to be a strong, effective writer.

I have a solid base of what language means and how it’s used. At the time, of course, I didn’t understand how knowing those words or parts of words would make a difference in my life. I didn’t understand, either, how writing a paper without Latinate diction would matter. Naturally, though, my teacher’s agenda came through — you learn what the Latin is and uncouple it from your writing when you can choose another way to say something. When you can maybe be more precise.

There are times, still, as an adult, when I get the cold sweats thinking about another Word Wealth test. I’ll have a nightmare that I forgot to make my flashcards or study. That this will be the test that means I’m a failure and I flunk out of the hardest high school class. I don’t think it happened, not even once, during high school. But the nightmares still pop up every once in a while.

And then there are times when I can toggle over to the reviews of Word Wealth on Amazon and see that these feelings are common among others who experienced this particular textbook in school:

Thank you, Word Wealth, and thank you to my teacher who, to this day, I still think was among those on my “have the most complicated feelings about” list. I can’t say that memorizing the beginning of Thoreau’s Walden Pond has done as much as learning how to differentiate words, their parts, and their meanings.

Thank you, Word Wealth, and thank you to my teacher who, to this day, I still think was among those on my “have the most complicated feelings about” list. I can’t say that memorizing the beginning of Thoreau’s Walden Pond has done as much as learning how to differentiate words, their parts, and their meanings.