In Praise of Plotless Books

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

You know what I’m sick of?

Systemic injustices in society carried out against its most vulnerable and ignored members of the population.

But you know what I’m also sick of, in relation to this thing I’m writing?

Books with plots!

Who needs ’em? What’s the last book you read? Oh yeah, that’s a good one, I’ve heard excellent things. But let me ask you this: did it have a plot? Yeah, I thought so!

A lot of “so-called” experts like Blake Snyder and Joseph Campbell will tell you all stories have to have some sort of narrative progression, one that is inherent in both the sequence of events and the protagonist’s personal journey. Well screw all of that! Life doesn’t follow a narrative, does it? Yeah, yeah, yeah? Didn’t think so! And we already have too many “plots” in real life as it is: political plots, massive plots of land, delicious plum platz from the old country. Enough with the plots, already!

So here’s a bunch of novels whose authors decided, “you know what? I don’t need no stinkin’ plots.” I salute them for their courage to ignore narrative cohesion and just write a bunch of unrelated nonsense!

This is the big one, the grandaddy of them all. Laurence Sterne was a clergyman who got tired of preaching the Bible (a book notorious for its use of narrative) and decided to write a book that was just some random dude sharing his opinions on random stuff. I don’t know how Sterne was able to channel his experience as a preacher into a bunch of opinionated ramblings that never go anywhere, but somehow he pulled it off.

But just because it has no logical beginning or end doesn’t mean the book isn’t interesting. Sterne, writing all the way back in the late 18th century (that’s the tricorn hat and powdered wig era for those of you who keep track of history by what people wore on their heads) pioneered a number of devices and styles that would come to define postmodernism two centuries later (that’s the era of bowler hats and pretentious berets).

Like, he was doing things like moving the text around the page, reordering the numbers of chapters, and even using stream-of-consciousness TWO HUNDRED YEARS before it was cool! I mean, can you imagine something you’re doing now that will only become popular centuries after you’re dead? So don’t quit doing stuff just because it’s not popular right now; you might just be way, way, way, way ahe—wait, one more: way ahead of your time.

You ever read a book where a lot of stuff happens, but once you get to the end, you’re like “Well, what was the point of that?” Well that book was probably On the Road, right? Yeah, I thought so.

A classic studied in most if not all high-schools, Kerouac’s most famous work details a series of roadtrips he and his friend, Dean, take across America in the late 40s. Aaaaand, that’s it. Sure, they encounter a ton of colourful characters based on real friends (and enemies) of Kerouac and have a lot of memorable adventures involving sex, drugs, and philosophical discussions, but that’s it.

Kerouac famously typed the entire novel on a single roll of paper, which was heavily-edited by the publishers. Eventually, the entire contents of the roll were published and if you read both editions, you can really see just how pointless the whole thing is.

It’s just a bunch of things that… happen, to a bunch of… people, most of whom are avoiding the responsibilities of their jobs and families back home. But maybe that’s the point, you know? Maybe life is just a bunch of stuff that happens to you while you’re busy making other plans*

*plans to neglect your pregnant wife and child, that is.

How’s this for a plot: a woman has a depressing life and is then hit by a car and dies. That’s the whole book. Well, OK, there’s a lot of rambling about the nature of storytelling, class statuses, desire vs reality, and what it means to be a person, but the thing you’ll remember most about this book is the hero getting hit by a car.

The last book Lispector ever wrote before she died, this book is all about human misery and our inability to escape the random chaos and suffering of our own existence. But it’s not as simple as all that.

The protagonist, Macabéa, is extremely poor, abused by her boyfriend, and ignored by everyone else, but she maintains a positive outlook on life until someone points out she has no reason to do so. The writer of the book (another different character, because I forgot to mention this book is metatextual) believes that by telling Macabéa’s story, he can find some meaning to life, even if it is ultimately unknowable. But as she dies, he too realizes that any meaning he writes about will just be fake, because he created it. He only finds true meaning not through the story he created, but only in the act of creating it.

Look, it’s a bleak book about how life is bleaker than you think it is, but it asks you to take a crucial look at yourself and everything you believe in order to better understand how you think as well as how to find true meaning in the midst of misery.

If you thought the car thing was sparse, try this on for size: a guy goes up an escalator.

Yup. That’s the whole book. It’s just some rando going up an escalator while he thinks about things.

But wait! I didn’t tell you what he’s thinking about! Oh man, you’re gonna love this. He’s thinking about cookies and shoe laces and hand dryers! Oh, and the aforementioned escalator, obviously.

Baker’s novella is an exploration of the physical world and how we understand our own existence largely through tactile experiences. It’s also about how great is it to eat cookies with just the right amount of milk so they turn into this delicious not-quite-soggy, not-quite-solid mash as you swallow them.

The book celebrates aesthetic pleasures, like having a straw in your coke so you can chew on a slice of pizza while you keep reading a cheap paperback in the warm sun. It’s mostly about being able to slow down, take the pressure off yourself and know that, no, you can’t understand everything around you, but you can still enjoy the little things and how dizzyingly complex even the act of tying your shoes can be (just FYI, that one takes several pages).

Widely praised for The Vegetarian, her first novel published in English, South Korean author Han Kang followed the story of one woman’s slow physical and mental breakdown (or is it a breakthrough?) with a book told from innumerable voices about a catastrophe too horrific to contain in a simple narrative.

Human Acts is about the Gwangju Uprising, where more than 600 people were killed after government troops began firing on protesting students. Chaos ensued as the military gunned down protesters attempting to surrender, a group of children playing nearby, and even their own troops whom they mistook for enemy forces.

Kang attempted to chronicle the brutal suppression and the subsequent government cover-up of the exact extent of the bloodshed by telling the same details over and over again from multiple perspectives, including a grieving mother, a journalist attempting to uncover the truth, a the ghost of a boy caught in the cross-fire.

By dissecting the events in this way, Kang eschews any sort of adherence to traditional plot structure and is able to make her story, seemingly about the a senseless loss of life, into a fractured work of art about class relations, political machinations, and human acts, both great and small, hopelessly cruel and unflinchingly compassionate.

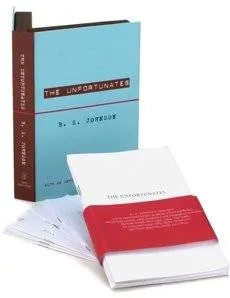

OK, so not only does this book not have a plot, but it’s not technically a book, either.

The Unfortunates was published in the newly-devised (and never reduplicated) “book-in-a-box” format, where you buy a container with a bunch of separately bound collections of pages that can be read in any order.

That’s right; with the exceptions of the first and final sections, the whole book can be scrambled up and read in any order you want. In theory, no two readers should have the same experience going through this, ahem, “book.” Unless of course none of them bother to mix up the pages and everyone just reads the book in the order they’re stacked on each other, but then what’s the p0int in that?

Johnson famously hated fiction, but still wrote novels for… some reason. Well, he claimed he wanted to capture the essence of real life in his writing, so he wrote about his own experiences but in a way that mimicked the seemingly disconnected disorder of the human mind.

The Unfortunates in particular chronicles a weekend at his friend’s house where they go out to the pub, watch a football match (or a “soccer game” for those of us who don’t think a game played primarily with your feet should have a logical-sounding name (Pfft, what’s next? Hand-ball? Basket-ball? Gimme a break!)) and discuss the most important thing on Johnson’s mind at the time: the book itself. Sorry, I meant “book.”

In terms of stories that don’t seem to be going anywhere, this one takes the cake, seeing as none of the distinct sections of the story are supposed to link up in any logical way. But it’s a completely unique “book… thing” like no other, not just because of it’s structure (or lack thereof), but also because it offers a a slice-of-life that is an actual slice of somebody’s life. The fact that Johnson’s friend died shortly after The Unfortunates was finished (and they even talk about his sickness many times throughout the “story”) gives The Unfortunates a potency and realness you couldn’t get from any other book. Or “book.” Or whatever.

So those are just some of the plotless novels you should check out. There are a ton of other great non-narrative books out there, but in keeping with the theme of this list, I don’t have any structure to this list, so I’m just gonna end it here.

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne

This is the big one, the grandaddy of them all. Laurence Sterne was a clergyman who got tired of preaching the Bible (a book notorious for its use of narrative) and decided to write a book that was just some random dude sharing his opinions on random stuff. I don’t know how Sterne was able to channel his experience as a preacher into a bunch of opinionated ramblings that never go anywhere, but somehow he pulled it off.

But just because it has no logical beginning or end doesn’t mean the book isn’t interesting. Sterne, writing all the way back in the late 18th century (that’s the tricorn hat and powdered wig era for those of you who keep track of history by what people wore on their heads) pioneered a number of devices and styles that would come to define postmodernism two centuries later (that’s the era of bowler hats and pretentious berets).

Like, he was doing things like moving the text around the page, reordering the numbers of chapters, and even using stream-of-consciousness TWO HUNDRED YEARS before it was cool! I mean, can you imagine something you’re doing now that will only become popular centuries after you’re dead? So don’t quit doing stuff just because it’s not popular right now; you might just be way, way, way, way ahe—wait, one more: way ahead of your time.

On the Road by Jack Kerouac

On the Road by Jack Kerouac

You ever read a book where a lot of stuff happens, but once you get to the end, you’re like “Well, what was the point of that?” Well that book was probably On the Road, right? Yeah, I thought so.

A classic studied in most if not all high-schools, Kerouac’s most famous work details a series of roadtrips he and his friend, Dean, take across America in the late 40s. Aaaaand, that’s it. Sure, they encounter a ton of colourful characters based on real friends (and enemies) of Kerouac and have a lot of memorable adventures involving sex, drugs, and philosophical discussions, but that’s it.

Kerouac famously typed the entire novel on a single roll of paper, which was heavily-edited by the publishers. Eventually, the entire contents of the roll were published and if you read both editions, you can really see just how pointless the whole thing is.

It’s just a bunch of things that… happen, to a bunch of… people, most of whom are avoiding the responsibilities of their jobs and families back home. But maybe that’s the point, you know? Maybe life is just a bunch of stuff that happens to you while you’re busy making other plans*

*plans to neglect your pregnant wife and child, that is.

The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector

The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector

How’s this for a plot: a woman has a depressing life and is then hit by a car and dies. That’s the whole book. Well, OK, there’s a lot of rambling about the nature of storytelling, class statuses, desire vs reality, and what it means to be a person, but the thing you’ll remember most about this book is the hero getting hit by a car.

The last book Lispector ever wrote before she died, this book is all about human misery and our inability to escape the random chaos and suffering of our own existence. But it’s not as simple as all that.

The protagonist, Macabéa, is extremely poor, abused by her boyfriend, and ignored by everyone else, but she maintains a positive outlook on life until someone points out she has no reason to do so. The writer of the book (another different character, because I forgot to mention this book is metatextual) believes that by telling Macabéa’s story, he can find some meaning to life, even if it is ultimately unknowable. But as she dies, he too realizes that any meaning he writes about will just be fake, because he created it. He only finds true meaning not through the story he created, but only in the act of creating it.

Look, it’s a bleak book about how life is bleaker than you think it is, but it asks you to take a crucial look at yourself and everything you believe in order to better understand how you think as well as how to find true meaning in the midst of misery.

The Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker

The Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker

If you thought the car thing was sparse, try this on for size: a guy goes up an escalator.

Yup. That’s the whole book. It’s just some rando going up an escalator while he thinks about things.

But wait! I didn’t tell you what he’s thinking about! Oh man, you’re gonna love this. He’s thinking about cookies and shoe laces and hand dryers! Oh, and the aforementioned escalator, obviously.

Baker’s novella is an exploration of the physical world and how we understand our own existence largely through tactile experiences. It’s also about how great is it to eat cookies with just the right amount of milk so they turn into this delicious not-quite-soggy, not-quite-solid mash as you swallow them.

The book celebrates aesthetic pleasures, like having a straw in your coke so you can chew on a slice of pizza while you keep reading a cheap paperback in the warm sun. It’s mostly about being able to slow down, take the pressure off yourself and know that, no, you can’t understand everything around you, but you can still enjoy the little things and how dizzyingly complex even the act of tying your shoes can be (just FYI, that one takes several pages).

Human Acts by Han Kang

Human Acts by Han Kang

Widely praised for The Vegetarian, her first novel published in English, South Korean author Han Kang followed the story of one woman’s slow physical and mental breakdown (or is it a breakthrough?) with a book told from innumerable voices about a catastrophe too horrific to contain in a simple narrative.

Human Acts is about the Gwangju Uprising, where more than 600 people were killed after government troops began firing on protesting students. Chaos ensued as the military gunned down protesters attempting to surrender, a group of children playing nearby, and even their own troops whom they mistook for enemy forces.

Kang attempted to chronicle the brutal suppression and the subsequent government cover-up of the exact extent of the bloodshed by telling the same details over and over again from multiple perspectives, including a grieving mother, a journalist attempting to uncover the truth, a the ghost of a boy caught in the cross-fire.

By dissecting the events in this way, Kang eschews any sort of adherence to traditional plot structure and is able to make her story, seemingly about the a senseless loss of life, into a fractured work of art about class relations, political machinations, and human acts, both great and small, hopelessly cruel and unflinchingly compassionate.

The Unfortunates by B.S. Johnson

The Unfortunates by B.S. Johnson

OK, so not only does this book not have a plot, but it’s not technically a book, either.

The Unfortunates was published in the newly-devised (and never reduplicated) “book-in-a-box” format, where you buy a container with a bunch of separately bound collections of pages that can be read in any order.

That’s right; with the exceptions of the first and final sections, the whole book can be scrambled up and read in any order you want. In theory, no two readers should have the same experience going through this, ahem, “book.” Unless of course none of them bother to mix up the pages and everyone just reads the book in the order they’re stacked on each other, but then what’s the p0int in that?

Johnson famously hated fiction, but still wrote novels for… some reason. Well, he claimed he wanted to capture the essence of real life in his writing, so he wrote about his own experiences but in a way that mimicked the seemingly disconnected disorder of the human mind.

The Unfortunates in particular chronicles a weekend at his friend’s house where they go out to the pub, watch a football match (or a “soccer game” for those of us who don’t think a game played primarily with your feet should have a logical-sounding name (Pfft, what’s next? Hand-ball? Basket-ball? Gimme a break!)) and discuss the most important thing on Johnson’s mind at the time: the book itself. Sorry, I meant “book.”

In terms of stories that don’t seem to be going anywhere, this one takes the cake, seeing as none of the distinct sections of the story are supposed to link up in any logical way. But it’s a completely unique “book… thing” like no other, not just because of it’s structure (or lack thereof), but also because it offers a a slice-of-life that is an actual slice of somebody’s life. The fact that Johnson’s friend died shortly after The Unfortunates was finished (and they even talk about his sickness many times throughout the “story”) gives The Unfortunates a potency and realness you couldn’t get from any other book. Or “book.” Or whatever.

So those are just some of the plotless novels you should check out. There are a ton of other great non-narrative books out there, but in keeping with the theme of this list, I don’t have any structure to this list, so I’m just gonna end it here.