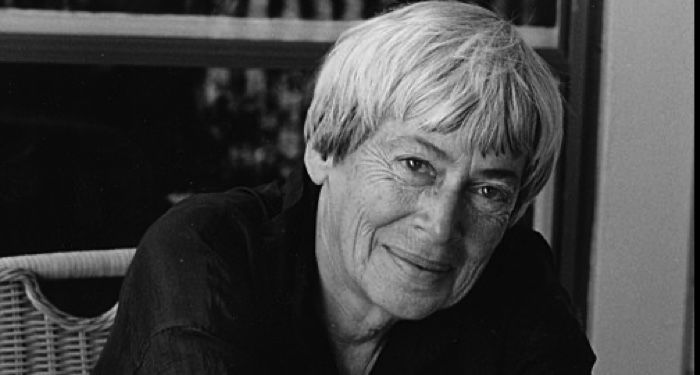

Who Was Ursula K. Le Guin?

Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom — poets, visionaries — realists of a larger reality.

Ursula K. Le Guin in her acceptance speech for the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2014

If you wanted to, depending on your reading speed, you could probably dedicate an entire year to reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s bibliography. In her lifetime she published 23 novels, 12 short story volumes, 11 poetry volumes, 13 children’s books, five essay collections, and four translated works. Needless to say, the woman was prolific when it came to writing, and she has the awards to show just how skilled she was at it. I think her Earthsea Cycle is just about one of the most recommended books out there, especially to young readers. She died in 2018, but has left a fingerprint on the literary world, inspiring authors who have themselves been included as some of the greats. She’s considered one of the most influential authors of the 20th century for a reason. But who was the person behind the massive library of books? How was she able to create worlds that were so incredibly fantastical but also so realistic and believable?

Early Life and Education

The life of the mind can be a very lively one. I was brought up to think and to question and to enjoy.

During the second World War my brothers all went into service and the summers in the Valley became lonely ones, just me and my parents in the old house. There was no TV then; we turned on the radio once a day to get the war news. Those summers of solitude and silence, a teenager wandering the hills on my own, no company, “nothing to do,” were very important to me. I think I started making my soul then.

Ursula K. Le Guin was born in California in 1929 to parents Theodora and Alfred Kroeber. Theodora was a writer and if you’re familiar with anthropological history, yes. I do mean that Alfred Kroeber.* But if you’re not familiar with anthropological history (who is, if you didn’t get a degree in this stuff), Kroeber is a big names in anthropological history. Alfred Kroeber was taught by Franz Boas (the father of American anthropology, who also taught Zora Neale Hurston) and is responsible for much of the theories cultural anthropologists use today.

Now, Alfred Kroeber was conducting anthropological work in the early 1900s*, so many of his ethnographic methods were not okay by today’s standards (NAGPRA exists for a reason) but growing up around a cultural anthropologist and hearing about how cultures and societies are made and evolve is probably what made Ursula’s work so realistic, even when set against a fantastical background filled with dragons or writing about cats with wings. It did not hurt that her brothers and her read plenty of science fiction magazines, mythology, and folklore on their own — most notably Norse mythology and Native American stories courtesy of their father reading out loud.

She loved the writings of Victor Hugo, William Wordsworth, Charles Dickens, and Boris Pasternak, who later became influences in her own works. They were not the only ones, however, as she also cited Tolkien and Tolstoy as stylistic influences. When it came to science fiction, she preferred the works of authors like Virginia Woolf and Jorges Luis Borges to the more well known authors at the time, like Heinlein, an author whose works she described as part of the “white man conquers the universe” tradition (I’m inclined to agree with her).

Being the daughter of well known scientists, there were plenty of big names that came to visit who she got to rub elbows with and whose conversations she got to listen in on, one of whom was physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (you may have heard that he then became the basis for the character Shevek in The Dispossessed, as I originally stated in this piece; this is however untrue and Le Guin put that myth to rest several times). She was extremely lucky in this regard: had her parents not been well-known and notable professors at Berkley during the Great Depression, it is difficult to say that she would have been the same type of writer, if her works would have touched so many people like they have.

When it comes to traditional education, Ursula almost achieved a doctorate and was granted a Fulbright grant to study in France. She quit her doctorate when she married her husband Charles Le Guin in 1953, though she still used her Masters of Arts degree in French to teach.* She would have three children with Charles: Elisabeth in 1957, Caroline in 1959, and Theodore in 1964.

Notable Works and Awards

Officially, her writing career started in the late 1950s, but Ursula began writing when she was 9 years old and tried to get a short story published at age 11. Her story was rejected, and while that didn’t stop her from writing, she didn’t submit anything for another 10 years. Her first published works were poems and short stories, starting in 1959. Ursula’s first published novel was Rocannon’s World in 1966, followed by Planet of Exile and City of Illusions in 1966 and 1967, creating the Hainish trilogy.

Ursula wasn’t put on the literary map, however, until her young adult novel A Wizard of Earthsea in 1968, and for good reason. Prior to that point, wizards tended to be the Gandalf type: old men with long white beards who spoke cryptically. If you’re a fan of the “boy goes to wizard school” plot or even just your general coming-of-age magic story, you have Ursula to thank for that. She essentially created that entire genre. After that came The Left Hand of Darkness, where you can clearly see her anthropologist upbringing. It explored gender and sexuality, as well as numerous feminist issues. It won her the Hugo and Nebula for Best Novel, making her the first woman to win both of those awards. The next book of hers to receive a Hugo would be The Word for World is Forest, a novel influenced by her anger over the Vietnam War, which dealt with colonialism and militarism. She called it her “most overt political statement” that she had made in a fictional work.

Ursula kept on with political overtures in her work, though, even if some of them were more subtle. The Dispossessed, for example, had anarchistic and utopian themes. It, like The Left Hand of Darkness, also won both the Hugo and the Nebula, making her the first person to win both awards for two books. In “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas,” the political overtures weren’t as subtle. Too many of her works to count carried themes of anarchism and later, Taoism. She regularly criticized state power and capitalism, and you can see echoes of theories from anarchists like Godwin, Kropotkin, and Debord in her writing. Going so far as to call herself an anarchist a couple of times, she made anarchism accessible to people who would probably never pick up books by those theorists. And she kept winning award after award after award.

In total, she:

- Won eight Hugos after being nominated 26 times, her last awarded posthumously.

- Won 24 Locus awards.

- Won six Nebula awards, four of those for Best Novel, out of 18 nominations. She was nominated for Best Novel six times, more than any other author.

- Was awarded one World Fantasy Award.

- Was given the 1973 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

- Earned a finalist position for the 1997 Pulitzer Prize.

- Awarded three James Tiptree Jr. Awards.

- Won three Jupiter Awards.

- Won a Gandalf Grand Master Award.

- Won a Pilgrim Award.

- Was given the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement.

- Was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame in 2001.

- Won an Eaton Award.

- Was named a Living Legend by the Library of Congress in 2001.

- Won the Margaret Edwards Award.

- Had a collection of works published by the Library of America while she was alive.

- Won the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters by the National Book Foundation.

- Made a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

- Was honored with stamp made of her in 2021 as part of the U.S. Postal Services Literary Arts series.

- Had a literary award named after her, the Ursula K. Le Guin Prize for Fiction. The first ever winner of the award is set to be announced this year, October 21st, 2022 on Ursula’s 93rd birthday.

Ursula’s Influences on the Literary World

You have no idea how nervous I am at the idea of writing to you. You’ve been one of my heroes since I bought A Wizard of Earthsea with my pocket money at the age of 11. Your SF shaped my head as a teenager, and told me that anything was possible and that events occur in context. Your essays on writing shaped me as a writer (something that occurs to me every time the train home passes through Poughkeepsie), and your later essays made me begin to think of myself as a feminist, and to change the way that I thought about men, about women, about language, about stories, about abortion.

Neil Gaiman, in an email to Ursula K. Le Guin prior to the National Book Awards in 2014

Her work has more than made its mark on the world of literature and affected so many. If you have ever heard the word “ansible” used in science fiction to describe an interstellar communication device (like in Doctor Who), you have Ursula K. Le Guin to thank for that. She coined the word in her Hainish universe. Prior to The Left Hand of Darkness, androgyny in science fiction, in literature as a whole, was all but unheard of. Now, you can turn on a show like Star Trek and see species like the Trill and J’naii, where gender is either not a concern or straight up viewed as primitive (TNG’s episode “The Outcast” is not even subtle in being a trans allegory). As mentioned before, Ursula is credited with the “wizard school” idea, appearing first in her Earthsea series.

Ursula K. Le Guin inspired numerous authors as well, not only Neil Gaiman (who is the reason “ansible” made it into Doctor Who) but also authors like Salman Rushdie, Jo Walton, David Mitchell, Vonda McIntyre, and Iain Banks.

More than that, Ursula made a point of writing several of her characters as non-white. Ged, in the Earthsea series, is described as having brown skin, as are most of the other characters. Which means that for a lot of non-white readers, reading the books from that series was their first experience reading a science fiction/fantasy novel about people that looked like them, especially in the ’60s when the first book came out. For many, it was the first time they felt included in a genre that typically exclude them.

Ursula The Rabble Rouser

You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.”

Ursula K. Le Guin in her book The Dispossessed

As Neil Gaiman said about her in his eulogy in the Paris Review, Ursula K. Le Guin was a rabble rouser in a harmless looking package. And oh boy was Ursula a rabble rouser. She knew her mind and what she stood for and refused to tolerate guff. When she accepted her medal from the National Book Foundation in 2014, she laid into big publishers there,* attacking them for their practices of charging libraries an arm and a leg for ebooks, limiting access to their books in general, the dangers of Amazon to the publishing industry after their treatment of Hachette, and above all, treating books and art as nothing but commodities.

She quit the Authors Guild in 2009 because of their support of Google’s book digitization project (also known as Google Books). Her resignation letter told them that they decided to deal with the devil, and she wasn’t wrong. In 2011, the Authors Guild filed a class action suit against Google as Google was scanning books that were still copyrighted, going against their promise to focus only on books in the public domain. The courts repeatedly sided with Google, saying copyright laws were not being violated due to technicalities.

She even turned down a Nebula Award for “The Diary of the Rose” in 1977, in protest of the Science Fiction Writers of America’s revoking of Stanisław Lem’s membership, most likely due to him criticizing American science fiction and the fact that he was willing to live in the Eastern Bloc. She didn’t want to receive an award for a story about political intolerance from a group of people who had just displayed political intolerance. More than that, she regularly pushed for better recognition of women in science fiction, fighting against the boys’ club that it was. She told the male writers on more than one occasion that science fiction as it was was no place for someone like her, and asked male authors to question themselves on if they have been complicit in building walls to keep female authors out. And what voices have they missed by doing so.

The woman was a spitfire, no other way to put it, and when she died in 2018, she left a hole in the world. She meant so much to so many, and never once tried to pull the ladder up behind her when it came to her success. I personally never got to meet her, something I regularly regret, but having her books so I can go back and reread as much as I want is a consolation to me. I hope it is to others, too.

Books aren’t just commodities; the profit motive is often in conflict with the aims of art. We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.

Ursula K. Le Guin in her acceptance speech for the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2014

If you need help figuring out where to start in Ursula’s massive bibliography, you can check out our reading pathways on her. Or, maybe, if you’re interested in some of the books she recommended others read, we have a handy list for that too.

I sometimes wonder what she would have to say about certain things, like the current court case between the DOJ and Penguin Random House, which our very own Annika Klein gave a good breakdown of back when it was announced.

Even with her gone, her voice still rings clear and never seems to lessen, no matter how many times you crack the spine on one of her books.

Editor’s Notes: The following corrections were made to this article since its initial publication, with thanks to the Ursula K Le Guin Literary Trust for their assistance.

- Ursela Le Guin’s mother and father were not both anthropologists and were not doing anthropological work together in the early 1900s. Theodora was a writer and Alfred an anthropologist, and they weren’t married until 1926.

- While knowing Oppenheimer influenced Le Guin’s portrayal of a physicist character, it is incorrect to say he was the entire basis for the character of Shevek in The Dispossessed. In the essay “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown,” Le Guin wrote, “The origin of my book The Dispossessed was equally clear, but it got very muddled before it ever became clear again. It too began with a person, seen much closer to, this time, and with intense vividness: a man, this time; a scientist, a physicist in fact; I saw the face more clearly than usual, a thin face, large clear eyes, and large ears—these, I think, may have come from a childhood memory of Robert Oppenheimer as a young man.”

- Le Guin did not receive Fulbright grants to continue her studies in London as originally stated. She lived in London because her husband Charles was doing research on sabbatical and was long out of her academic career by that time.

- It was originally stated that Le Guin laid into the National Book Foundation committee when she received the NBF medal in 2014; this is incorrect—her speech was entirely aimed at publishers.