Who Was Pat Parker?

Long before the rise of social movements like Black Lives Matter or #BlackGirlMagic, long before intersectional feminism was even a concern on the minds of feminist leaders, there were Black artists, poets, and thinkers who understood that the work wasn’t going to get done unless someone gets going. Those familiar with feminist literature will likely have heard the name Audre Lorde, but the name of one of her closest friends is often lost between the lines of history: Pat Parker.

In an era where Betty Friedan infamously told lesbians that they had no place in the National Organization for Women (NOW) during the rise of second-wave feminism in the 1960s and 1970s, it was poets like Lorde and Parker who got down to business and paved their own path. Indeed, their work would become highly influential on both the feminist and gay rights movements, despite Parker’s work being comparatively less remembered than that of Lorde.

Parker grew up in poverty in Houston, Texas. Born Patricia Cooks, her parents held blue-collar, working-class positions: her mother was a domestic worker, and her father worked with tires. The poet would later refer to her early years as “Texas hell,” a life she got away from as soon as she could. She moved to Los Angeles in 1962 after one of her uncles had died in police custody and a community mob had murdered a young boy for being gay. Radicalized quite early on from the traumatic experiences of her childhood, Parker knew very quickly that Texas was never her home.

After moving to California, she studied at Los Angeles City College and, for a time, was enrolled in Creative Writing at San Francisco State University but never graduated. During this time, she married her first husband, Ed Bullins, a playwright and a Minister of Culture for the Black Panther movement. They relocated to the Bay Area of San Francisco around 1964, and by Parker’s account, they separated once Bullins became violent. She swiftly remarried to Robert F. Parker, whose name she would keep, but started to learn that a life of heterosexual marriage and dominion was not in the cards.

As such, following her second divorce, Parker was done trying to fit into an assigned box. Like many Black women of her era, she was radicalized by the triumphs and failures of the Civil Rights Movement as well as the advent of modern feminism’s second wave, which, from a mainstream perspective, seemed intent on continuing to marginalize women of racial minorities, let alone sexual minorities. Friedan notoriously referred to lesbians as the “lavender menace” of the feminist movement, as she believed their plight was different from that of straight (white) women seeking to smash the notion that they belonged in the kitchen.

Active in the Black Panther Party, Parker was radicalized not only to begin a life as a poet and writer but as a Black lesbian woman, which, in the late 1960s, was a challenge. Empowered by her poetry, she used her work in the fight for women’s rights, gay rights, civil rights, and gender equality. Among her most provocative and subversive poetry of the time period was a 1978 poem entitled “For Willyce,” which describes a session of lesbian lovemaking and famously ends with the lines, “here it is, some dude’s / getting credit for what / a woman / has done, / again.”

Throughout the 1970s, Parker strengthened her craft by continuing to write rebellious poetry and teaching creative writing workshops. She also began healing past trauma through her work, including the murder of her sister at the hands of her ex-husband by way of the poem “Woman Slaughter.” It was these personal instances of violence at the hands of men, which had occurred throughout her entire life, that fueled the poet to further the fight for women’s rights and equality.

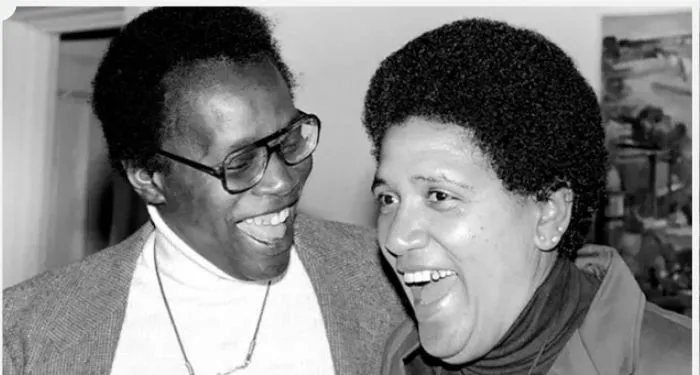

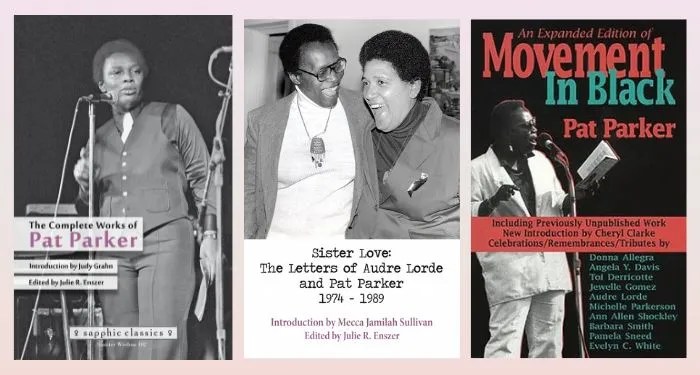

She met fellow Black lesbian poet Audre Lorde around 1969, and their friendship grew into the next decade with the publication of Parker’s debut poetry collection Child of Myself in 1972. By this time, Parker had settled in Oakland, California, and Lorde was something of a nomad, sometimes taking up residence in New York while always known to be traveling abroad. Their friendship during this period was conducted heavily in written correspondence, in which they shared advice and words of encouragement with each other on everything under the sun.

Although she is best remembered in the feminist movement as a poet, Parker also published essays, short stories, and plays in her lifetime. In a speech given in the 1980s, she relayed her passion for social change and reminded future generations that we all have to show up in order for change to actually happen: “I am a revolutionary feminist because I want me to be free. And it is critically important to me that you are here, that your commitment to revolution is based on the fact that you want revolution for yourself…if we dare to struggle, dare to win, this earth will turn over.” Parker died of breast cancer in 1989.

While her work is less widely known than that of Lorde or some of their contemporaries, Parker’s poetry and activism remain inspiring well into the digital age of feminism, when it is imperative that all women see themselves represented in the fight for women’s rights. Parker wanted herself to be free, but she also wanted all women to be free.