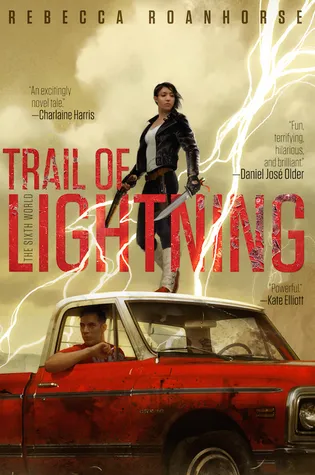

When Lived Experience is the Best Research: Learning Navajo and Writing TRAIL OF LIGHTNING

Yale graduate and lawyer Rebecca Roanhorse is an Ohkay Owingeh/Black writer of Indigenous futurism. Residing in Northern New Mexico with her husband, daughter, and pug, Roanhorse is set to release her debut novel Trail of Lightning (book one of the Six World series) in the summer of 2018. Following Trail of Lightning is a children’s book, Race to the Sun set to be released sometime in 2019.

Rebecca Roanhorse is a Nebula Winner and Hugo, Sturgeon, and Locus Award Finalist, as well as a Campbell Award Finalist.

Yale graduate and lawyer Rebecca Roanhorse is an Ohkay Owingeh/Black writer of Indigenous futurism. Residing in Northern New Mexico with her husband, daughter, and pug, Roanhorse is set to release her debut novel Trail of Lightning (book one of the Six World series) in the summer of 2018. Following Trail of Lightning is a children’s book, Race to the Sun set to be released sometime in 2019.

Rebecca Roanhorse is a Nebula Winner and Hugo, Sturgeon, and Locus Award Finalist, as well as a Campbell Award Finalist.

My daughter’s first word was “łį́į́’”. Don’t worry. I can’t pronounce it, either.

She said the word as we were driving home from her sitter’s house. I’d spent the day working at the legal aid office in Window Rock, Arizona, the capital of the Navajo Nation. She had spent the day playing with her grandma, auntie and cousins. (Don’t ask me the actual relations of all these folks. They were her relatives, and that’s good enough.) Her extended family, including my husband’s parents with whom we were living at the time, were all fluent in the Navajo language, or Diné Bizaad. So, it shouldn’t have been a surprise when my kiddo pointed out the window to a field of grazing horses and exclaimed, “łį́į́’!”

I was shocked at first. Up until now, her most eloquent moment had been stringing the sounds “doobie-doobie-doobie” together while creating an impressive amount of drool. And łį́į́’ is such a difficult work for non-native speakers to pronounce correctly, I honestly wasn’t sure that’s what she had said at all. But when we got home I excitedly tried to replicate the word to my Navajo husband and…well, at first he had no idea what I was trying to say. But we puzzled it out with the help of a baby obsessed with repeating her new word, and we figured out she was, indeed, saying the Navajo word for “horse.” I would have preferred “shima,” the Navajo word for mother, but I’d take horse in a pinch.

I’d been working on learning some basics of the language. My job in legal aid meant I often served a Navajo population that was elderly and spoke little English. If I wanted to communicate effectively and respectfully, I needed to learn some Diné Bizaad. I think many non-Natives might be surprised how much Navajo is spoken and written daily on the reservation. If you want to do your grocery shopping or you need to fill our government forms or you simply want to know what’s going on at the local high school that weekend, it helps to be able to read at least a bit of the language.

At the time, I was also practicing law in the Navajo courts, and much of Navajo law is based on Navajo concepts and teachings. Many concepts are not translated. Sometimes they aren’t translated because there is no good English equivalent, and sometimes if you are on Navajo land practicing in Navajo courts espousing Navajo principles of law, it behooves you to know the language. So I became functional in Navajo, in a very limited sense, and enamored of the language as a whole.

Just as it should not have been a surprise that my daughter’s first word was a Navajo word, it should not be a surprise that my first novel was set on the Navajo Nation and included a lot of Navajo language, often without translation. After two years of living and working there, the world and way of life was becoming part of who I was, and it just made sense. I could see the strength and beauty in the language and culture. When I imagined my post-apocalyptic fantasy novel, I was sure Natives would be the people who survived an apocalypse. After all, hadn’t we already survived European invasion? Native people, including my own Pueblo people, were resourceful, smart, and above all, survivors. I didn’t think a little thing like the end of the world would slow us down much.

So, I set out to write a story set in the genre that I love, science fiction and fantasy, that incorporated Navajo ways and stories and language. I wanted to make the world I created, however make-believe, feel like being back on the rez, both to people who knew the place intimately, and for those who had never set foot west of the Mississippi, or on the North American continent at all. But capturing that world couldn’t be done without the language. Diné Bizaad is such an essential part of Navajo life. To leave it out would have made the story ring false.

Some people have asked why I didn’t translate the words or provide a glossary, but I think most readers, with a little effort and ingenuity, can figure out what the words mean by context or, if necessary, a quick Google search. I also took a cue from authors like Daniel José Older, who explained that when he used Spanish in his books—urban fantasy books at that—he didn’t italicize or translate the words because Spanish-speakers aren’t pausing to translate as they speak, and they certainly aren’t italicizing the words as they say them. It is a natural back and forth, an interplay between languages, that makes for reality. And despite writing fantasy, I was trying to offer readers, Navajo and non-Navajo, a bit of reality.

If you haven’t heard Diné Bizaad spoken, it’s easy to find online sources where you find many of the most common words you would hear pronounced. I recommend Navajo Word of the Day. There are also some great language speakers on YouTube, willing to share and educate you on the language. Check out YouTuber daybreakwarrior for a start.

As for me, my Navajo reading and comprehension get better every time I go back, but I still can’t pronounce “łį́į́’.” But I keep trying. It’s worth it.