What is the Millennial Genre?

Contemporary fiction is wide and varied in terms of genre. It feels like there are more micro-genres than ever before, more authors pushing the boundaries of what is thought to be a specific genre and upending conventions. Despite this sense of play, the idea of a “millennial genre” has stuck as a moniker for fiction thought to define the millennial generation. When we talk about what the millennial genre is, we have to understand that it’s more than just a genre.

In this article, I mean “millennial fiction” as works written by authors born in the millennial generation, between 1981 and 1996. Millennials who grew up in the United States can point to a variety of world-shaking events that defined their childhoods: 9/11 and the subsequent invasion of Iraq, the Great Recession of 2008, and the widespread adoption of the internet. In adulthood, we’ve seen the upending of political systems and the COVID-19 pandemic.

There’s a fair amount of worry about millennials’ attitudes towards their own adulthood. Are we too lazy or too selfish to buy houses, start families, and contribute correctly as citizens? For many of us, the financial bomb of the recession slowed career growth and changed our conception of what life was supposed to be. Growing up, I was told I could do or be anything, but as those options very clearly shrank by circumstance and necessity, a malaise that felt specifically millennial started to set in. In college and right after it, this feeling was paired with hand-wringing in the media about if millennials were too lazy to work, if we cared too much, if we didn’t care enough, and how we were all wasting our money on avocado toast.

What defines a millennial novel?

Although writers of the past, like Bret Easton Ellis, have said millennials have no interest in literature, the book-buying trends of millennials argue against this assertion. The concerns of millennial novels are more fractured, most likely because of the dissolution of the monoculture and the growing diversity of published authors that allows us to read widely about many different people.

Instead of focusing on one novel supposed to define the generation, there are a variety of novels that have reverberated within various communities. Additionally, millennials are only just approaching middle age, so it’s not like we’ve had enough time or distance for certain novels to become ageless classics.

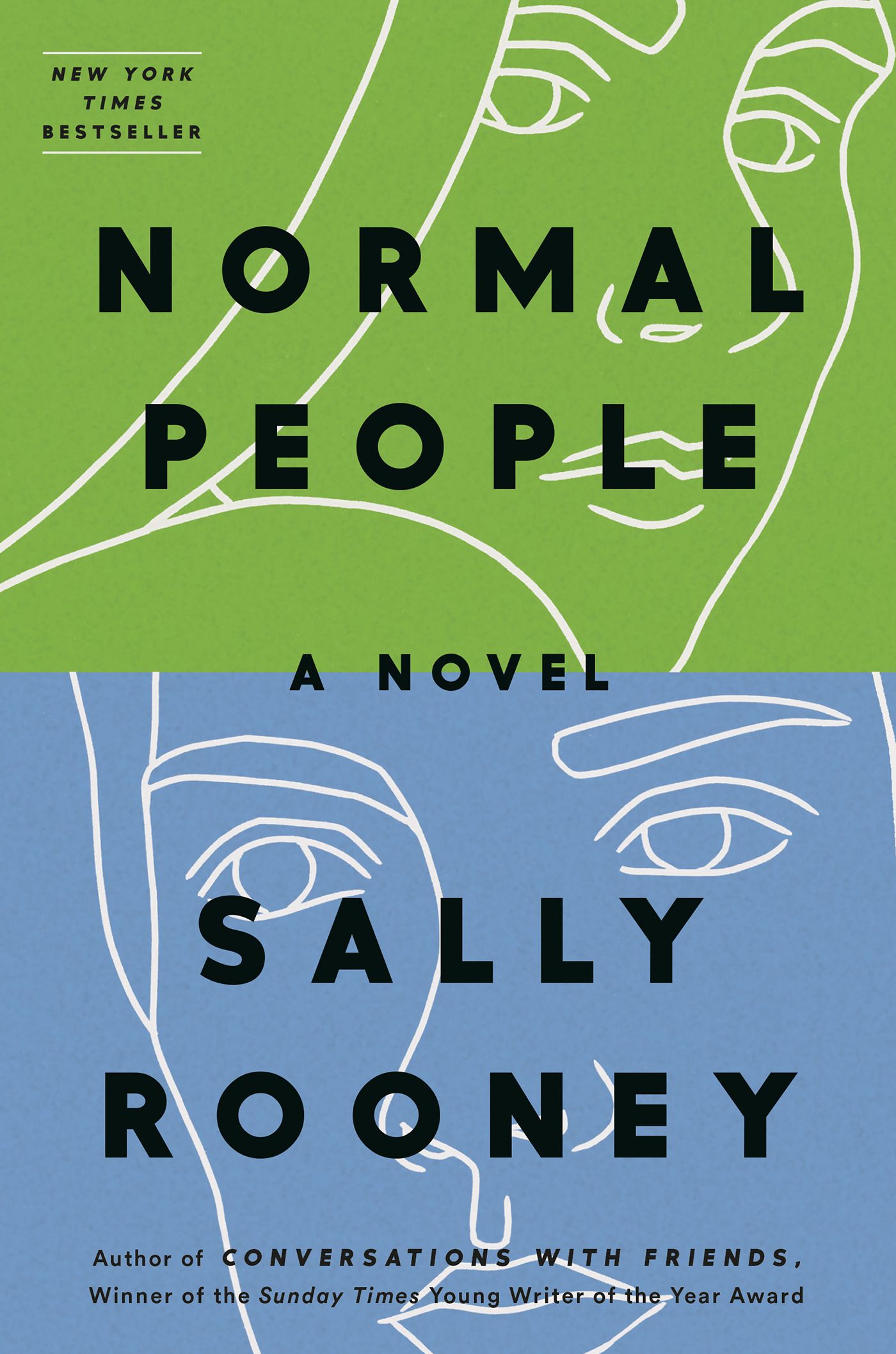

However, one author tends to rise to the top of the discourse of millennial novelists: Sally Rooney. The focus of her novels turns inward to allow her characters to explore the oppressive anxieties of living in a world where it feels like everything is stacked against you. Paradoxically, her work means to resist the easy categorization of “voice of a generation.” The writer Betsy Reed examines this push for a definitive millennial voice:

“In contrast to the ways they are marketed and their media reception, millennial novels, if they have a common aim, push against labels, pedestals and the uncritical lauding of spokespeople. They care more about being relatable to a specific audience than a universal one… Their fictional worlds lambast our need for external validation and commodified selfhood of the kind that feeds late capitalism, even as they acknowledge their complicity and the impossibility of extrication.”

The millennial novel has also been referred to as “slacker fiction,” which is sort of a negative moniker for the distinctly unsettled lives that millennials are forced to live. A lack of financial, job, home, and general life security is coupled with novels about characters who are searching and grasping for something to hold onto. It can read like slacker fiction, but maybe it’s the malaise created by not knowing where the future will take us.

The sleep that the main character of My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Otessa Moshfegh experiences is an apt illustration of this issue. Did the main character go to sleep because she was lazy or because the world was simply too much to deal with? Moshfegh’s own tension with her iconic status through the rise of her novel on TikTok is another illustration of the struggle of a millennial novelist: they understand the danger of the high pedestal.

Expanding the Genre

Though it feels like Sally Rooney is the most referenced author of millennial fiction, non-white writers have also managed to break through with beloved books as well. Severance by Ling Ma, Queenie by Candice Carty-Williame, Luster by Raven Leliani, and Everything You Ever Wanted by Luiza Sama are a few prominent examples.

I find pinning down an exact definition of millennial fiction to be difficult because so much of it is about the author’s specific experience. A large number of people relating to a very specific story is the joy of a great novel. The authors don’t want to be the voice of their generations but find some relatability in the specific experiences.

It is also important to point out that these novels are very focused on a certain slice of the world. The literary critic Masiyaleti Mbewe wonders if the millennial novel can have an African focus as well:

“The critical construction of the millennial novel emerges from a white Western cultural apparatus that’s dedicated to centering a certain kind of narrative voice, whose concerns are presumably not shared by nonwhite, non-Western protagonists (and readers). But surely, if anyone can accurately express the socioeconomic anxieties of a generation whose personal and communal hopes for the future have been radically disappointed, it would be African writers.”

The millennial fiction moniker is both very wide and somewhat limiting. Writers from various countries are shoved into country-specific categories, setting boundaries around how readers can find commonalities in their experiences with books from around the world. Mbewe finds this an important category of inquiry because the genre reflects the concerns of the moment: “I find value in these generational categories of literary work because recognizing how literature operates as a historical archive of the sentiments of our time is important. But will the literary world really reckon with what these categories overlook?”

As millennial fiction ages, and we continue to reimagine the course of our lives away from the previous generations’ outlines, it’s necessary for readers and writers to continue to widen the definition of the millennial experience. Though many popular millennial novels look within, seeking out these novels about diverse, specific experiences is our way of looking outward for connection.