What Is the Golden Age?

If you’re new to comics, you’ve probably seen terms like “Golden Age” and “Silver Age” bandied about without a lot of context, and possibly “Bronze Age,” “Modern Age,” and a handful of others. But what time periods do these so-called Ages cover, and—what I think is a more interesting question—what does each term really mean? Let’s get into that question, starting with a closer look at the Golden Age.

[Note: I’ll be talking pretty much exclusively about American superhero comics here, since that’s largely where the “Age” terminology sprang from, but obviously other genres and cultural traditions evolved alongside or apart from the U.S. capes and tights set! Comics are not and have never been a monolith.]

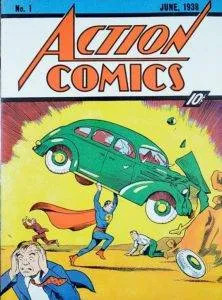

Comics historians can and will argue the exact parameters of each era until the Batcows come home, but most agree that the Golden Age of Comics began in 1938 with the debut of Superman, who’s generally considered the first comic book superhero (which is also a topic that we can split hairs over forever, but that’s a whole ‘nother article), and ended some time in the early to mid-1950s.

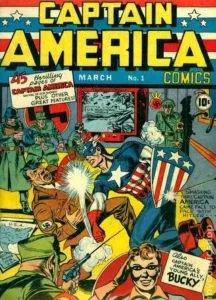

Comic books—pulpy periodicals of sequential art—had been around since the early ‘30s, but the medium exploded with the unprecedented popularity of Superman. Suddenly all the publishers wanted a slice of that pie, and a host of long-johned vigilantes appeared in the funny books. Since DC’s lawyers were quick to go after anyone they saw as infringing on their trademark—they successfully sued Fox Features Syndicate over their blatant ripoff, Wonder Man, and battled Fawcett for years over Captain Marvel—writers and artists did their best to differentiate their creations from the Man of Steel. This meant that the nascent genre was soon bristling with not just strongmen, but speedsters, magicians, detectives, scientists, spooks, and masked vigilantes of every stripe. As the war “over there” gained prominence, super soldiers and other patriotic do-gooders joined this colorful cast.

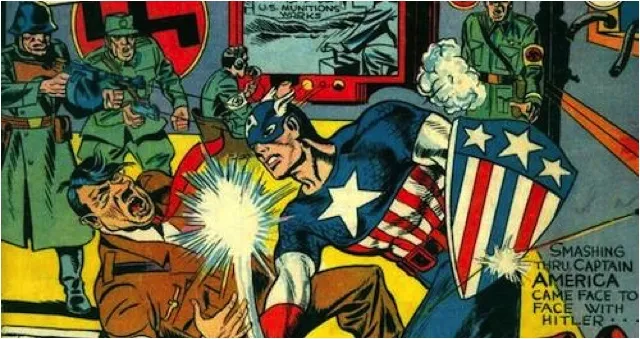

Golden Age comics were experimental and varied, as befits a nascent genre and medium, but they tended to share a few trademarks. Their heroes usually fought gangsters, crooked politicians and businessmen (especially in the New Deal late ‘30s), and Fifth Columnists, with only a few legit supervillains dotting the four color landscape. They skewed towards urban settings and noir tones, in keeping with their prose cousins in the pulp magazines and popular radio heroes like the Shadow. Orphans were relentlessly plucky, and female characters were often hard-nosed career women with guns in their handbags and no time for romance. (Early Lois Lane, of course, is the patron saint of these dauntless dames.) Racist depictions of minorities were extremely common and are often stomach-turning to read now—Japanese characters got the harshest treatment after Pearl Harbor, but the Spirit’s African-American sidekick, Ebony White, was straight out of the minstrel show tradition, and in general comics at the time were full of harem girls, “Indian savages,” generic jungle tribes, and other equally hateful stereotypes.

Comics historians can and will argue the exact parameters of each era until the Batcows come home, but most agree that the Golden Age of Comics began in 1938 with the debut of Superman, who’s generally considered the first comic book superhero (which is also a topic that we can split hairs over forever, but that’s a whole ‘nother article), and ended some time in the early to mid-1950s.

Comic books—pulpy periodicals of sequential art—had been around since the early ‘30s, but the medium exploded with the unprecedented popularity of Superman. Suddenly all the publishers wanted a slice of that pie, and a host of long-johned vigilantes appeared in the funny books. Since DC’s lawyers were quick to go after anyone they saw as infringing on their trademark—they successfully sued Fox Features Syndicate over their blatant ripoff, Wonder Man, and battled Fawcett for years over Captain Marvel—writers and artists did their best to differentiate their creations from the Man of Steel. This meant that the nascent genre was soon bristling with not just strongmen, but speedsters, magicians, detectives, scientists, spooks, and masked vigilantes of every stripe. As the war “over there” gained prominence, super soldiers and other patriotic do-gooders joined this colorful cast.

Golden Age comics were experimental and varied, as befits a nascent genre and medium, but they tended to share a few trademarks. Their heroes usually fought gangsters, crooked politicians and businessmen (especially in the New Deal late ‘30s), and Fifth Columnists, with only a few legit supervillains dotting the four color landscape. They skewed towards urban settings and noir tones, in keeping with their prose cousins in the pulp magazines and popular radio heroes like the Shadow. Orphans were relentlessly plucky, and female characters were often hard-nosed career women with guns in their handbags and no time for romance. (Early Lois Lane, of course, is the patron saint of these dauntless dames.) Racist depictions of minorities were extremely common and are often stomach-turning to read now—Japanese characters got the harshest treatment after Pearl Harbor, but the Spirit’s African-American sidekick, Ebony White, was straight out of the minstrel show tradition, and in general comics at the time were full of harem girls, “Indian savages,” generic jungle tribes, and other equally hateful stereotypes.

Comics of the era were also often crude, from a technical standpoint—although to be fair, even the finest art tends to degrade when printed on cheap newsprint, rolled up and shoved in some ten-year-old’s back pocket, and left in a warehouse for three quarters of a century. Stunning art could and did exist—Joe Shuster’s early work on Superman, C. C. Beck’s Captain Marvel, and Will Eisner’s Spirit spring to mind—but many of these comics were churned out at an incredible volume for low wages by would-be fine artists just trying to make ends meet until they could get more lucrative and respectable work in advertising. The idea of comics as a legitimate form of artistic expression and storytelling was still to come. Still, the slapdash nature of the industry helped to keep it fast-paced and experimental. A particular hero’s powers might change wildly from one issue to the next largely because the writer hadn’t bothered to remember what he wrote in the previous script, but it also bespoke the “anything goes” energy of the Golden Age.

Comics were hugely popular in the ‘40s—over 90% of boys and girls in America read them (ask your grandma!)—but in the years following World War II, superheroes fell out of vogue in favor of other genres like horror, crime, and romance. It would take over a decade for them to come back in a big way, thus kicking off the Silver Age…but that’s a story for next time!

Looking to check out some Golden Age comics? DC’s got a few options if you want to read Superman’s earliest adventures, from the fancy-pants Superman: The Golden Age Omnibus (why yes, I would love it if you got me this for my birthday!) to the more affordable paperbacks Superman: The Golden Age or The Superman Chronicles, the latter of which reprints all Superman appearances in chronological order. Batman’s similarly represented with Batman: The Golden Age Omnibus, Batman: The Golden Age, and The Batman Chronicles. For my money, though, the most fun is to be had with The Wonder Woman Chronicles – Golden Age Wonder Woman is infamously, fabulously weird, and not to be missed.

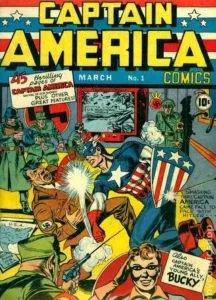

Most of Marvel’s marquee characters wouldn’t show up until the Silver Age. The big exception is of course Captain America, who’s got his own fancy omnibus – Golden Age Captain America Omnibus – as well as the Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Captain America. You can also check out Namor, Marvel’s first superpowered star, in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Sub-Mariner, or read up on both Namor and the original android Human Torch in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Marvel Comics. Marvel gets additional props for actively courting female readers to make up for the postwar sales slump with female superheroes; check out the longest-running of those heroines, Venus, in—you guessed it—Marvel Masterworks: Atlas Era Venus.

The Golden Age wasn’t just what we now think of as the Big Two, though – the biggest seller during World War II was actually Fawcett Comics’ Captain Marvel. This version of Cap is now owned by DC due to a convoluted lawsuit and his Golden Age adventures aren’t reprinted super frequently, but you can find some of them in Shazam! A Celebration of 75 Years…or, since they’re now public domain, free and legal to download at The Digital Comic Museum. The DCM’s also a good source for another Golden Age standout now owned by DC, Jack Cole’s Plastic Man (then published by Quality Comics), one of the most inventive heroes of the time. Finally, Will Eisner was one of the first to take comics seriously as a budding artform. Read some of his landmark work on the Spirit (with the aforementioned caveat about Ebony White) in Will Eisner’s The Spirit: A Celebration of 75 Years, or again in the DCM’s Quality Comics collection.

If you’re interested in more non-fiction on the Golden Age, you can check out The Golden Age of DC Comics by Paul Levitz, or Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the Superhero by Danny Fingeroth. See you next time, when we biff-bam-pow our way into the Silver Age!

Comics of the era were also often crude, from a technical standpoint—although to be fair, even the finest art tends to degrade when printed on cheap newsprint, rolled up and shoved in some ten-year-old’s back pocket, and left in a warehouse for three quarters of a century. Stunning art could and did exist—Joe Shuster’s early work on Superman, C. C. Beck’s Captain Marvel, and Will Eisner’s Spirit spring to mind—but many of these comics were churned out at an incredible volume for low wages by would-be fine artists just trying to make ends meet until they could get more lucrative and respectable work in advertising. The idea of comics as a legitimate form of artistic expression and storytelling was still to come. Still, the slapdash nature of the industry helped to keep it fast-paced and experimental. A particular hero’s powers might change wildly from one issue to the next largely because the writer hadn’t bothered to remember what he wrote in the previous script, but it also bespoke the “anything goes” energy of the Golden Age.

Comics were hugely popular in the ‘40s—over 90% of boys and girls in America read them (ask your grandma!)—but in the years following World War II, superheroes fell out of vogue in favor of other genres like horror, crime, and romance. It would take over a decade for them to come back in a big way, thus kicking off the Silver Age…but that’s a story for next time!

Looking to check out some Golden Age comics? DC’s got a few options if you want to read Superman’s earliest adventures, from the fancy-pants Superman: The Golden Age Omnibus (why yes, I would love it if you got me this for my birthday!) to the more affordable paperbacks Superman: The Golden Age or The Superman Chronicles, the latter of which reprints all Superman appearances in chronological order. Batman’s similarly represented with Batman: The Golden Age Omnibus, Batman: The Golden Age, and The Batman Chronicles. For my money, though, the most fun is to be had with The Wonder Woman Chronicles – Golden Age Wonder Woman is infamously, fabulously weird, and not to be missed.

Most of Marvel’s marquee characters wouldn’t show up until the Silver Age. The big exception is of course Captain America, who’s got his own fancy omnibus – Golden Age Captain America Omnibus – as well as the Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Captain America. You can also check out Namor, Marvel’s first superpowered star, in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Sub-Mariner, or read up on both Namor and the original android Human Torch in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Marvel Comics. Marvel gets additional props for actively courting female readers to make up for the postwar sales slump with female superheroes; check out the longest-running of those heroines, Venus, in—you guessed it—Marvel Masterworks: Atlas Era Venus.

The Golden Age wasn’t just what we now think of as the Big Two, though – the biggest seller during World War II was actually Fawcett Comics’ Captain Marvel. This version of Cap is now owned by DC due to a convoluted lawsuit and his Golden Age adventures aren’t reprinted super frequently, but you can find some of them in Shazam! A Celebration of 75 Years…or, since they’re now public domain, free and legal to download at The Digital Comic Museum. The DCM’s also a good source for another Golden Age standout now owned by DC, Jack Cole’s Plastic Man (then published by Quality Comics), one of the most inventive heroes of the time. Finally, Will Eisner was one of the first to take comics seriously as a budding artform. Read some of his landmark work on the Spirit (with the aforementioned caveat about Ebony White) in Will Eisner’s The Spirit: A Celebration of 75 Years, or again in the DCM’s Quality Comics collection.

If you’re interested in more non-fiction on the Golden Age, you can check out The Golden Age of DC Comics by Paul Levitz, or Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the Superhero by Danny Fingeroth. See you next time, when we biff-bam-pow our way into the Silver Age!

Comics historians can and will argue the exact parameters of each era until the Batcows come home, but most agree that the Golden Age of Comics began in 1938 with the debut of Superman, who’s generally considered the first comic book superhero (which is also a topic that we can split hairs over forever, but that’s a whole ‘nother article), and ended some time in the early to mid-1950s.

Comic books—pulpy periodicals of sequential art—had been around since the early ‘30s, but the medium exploded with the unprecedented popularity of Superman. Suddenly all the publishers wanted a slice of that pie, and a host of long-johned vigilantes appeared in the funny books. Since DC’s lawyers were quick to go after anyone they saw as infringing on their trademark—they successfully sued Fox Features Syndicate over their blatant ripoff, Wonder Man, and battled Fawcett for years over Captain Marvel—writers and artists did their best to differentiate their creations from the Man of Steel. This meant that the nascent genre was soon bristling with not just strongmen, but speedsters, magicians, detectives, scientists, spooks, and masked vigilantes of every stripe. As the war “over there” gained prominence, super soldiers and other patriotic do-gooders joined this colorful cast.

Golden Age comics were experimental and varied, as befits a nascent genre and medium, but they tended to share a few trademarks. Their heroes usually fought gangsters, crooked politicians and businessmen (especially in the New Deal late ‘30s), and Fifth Columnists, with only a few legit supervillains dotting the four color landscape. They skewed towards urban settings and noir tones, in keeping with their prose cousins in the pulp magazines and popular radio heroes like the Shadow. Orphans were relentlessly plucky, and female characters were often hard-nosed career women with guns in their handbags and no time for romance. (Early Lois Lane, of course, is the patron saint of these dauntless dames.) Racist depictions of minorities were extremely common and are often stomach-turning to read now—Japanese characters got the harshest treatment after Pearl Harbor, but the Spirit’s African-American sidekick, Ebony White, was straight out of the minstrel show tradition, and in general comics at the time were full of harem girls, “Indian savages,” generic jungle tribes, and other equally hateful stereotypes.

Comics historians can and will argue the exact parameters of each era until the Batcows come home, but most agree that the Golden Age of Comics began in 1938 with the debut of Superman, who’s generally considered the first comic book superhero (which is also a topic that we can split hairs over forever, but that’s a whole ‘nother article), and ended some time in the early to mid-1950s.

Comic books—pulpy periodicals of sequential art—had been around since the early ‘30s, but the medium exploded with the unprecedented popularity of Superman. Suddenly all the publishers wanted a slice of that pie, and a host of long-johned vigilantes appeared in the funny books. Since DC’s lawyers were quick to go after anyone they saw as infringing on their trademark—they successfully sued Fox Features Syndicate over their blatant ripoff, Wonder Man, and battled Fawcett for years over Captain Marvel—writers and artists did their best to differentiate their creations from the Man of Steel. This meant that the nascent genre was soon bristling with not just strongmen, but speedsters, magicians, detectives, scientists, spooks, and masked vigilantes of every stripe. As the war “over there” gained prominence, super soldiers and other patriotic do-gooders joined this colorful cast.

Golden Age comics were experimental and varied, as befits a nascent genre and medium, but they tended to share a few trademarks. Their heroes usually fought gangsters, crooked politicians and businessmen (especially in the New Deal late ‘30s), and Fifth Columnists, with only a few legit supervillains dotting the four color landscape. They skewed towards urban settings and noir tones, in keeping with their prose cousins in the pulp magazines and popular radio heroes like the Shadow. Orphans were relentlessly plucky, and female characters were often hard-nosed career women with guns in their handbags and no time for romance. (Early Lois Lane, of course, is the patron saint of these dauntless dames.) Racist depictions of minorities were extremely common and are often stomach-turning to read now—Japanese characters got the harshest treatment after Pearl Harbor, but the Spirit’s African-American sidekick, Ebony White, was straight out of the minstrel show tradition, and in general comics at the time were full of harem girls, “Indian savages,” generic jungle tribes, and other equally hateful stereotypes.

Comics of the era were also often crude, from a technical standpoint—although to be fair, even the finest art tends to degrade when printed on cheap newsprint, rolled up and shoved in some ten-year-old’s back pocket, and left in a warehouse for three quarters of a century. Stunning art could and did exist—Joe Shuster’s early work on Superman, C. C. Beck’s Captain Marvel, and Will Eisner’s Spirit spring to mind—but many of these comics were churned out at an incredible volume for low wages by would-be fine artists just trying to make ends meet until they could get more lucrative and respectable work in advertising. The idea of comics as a legitimate form of artistic expression and storytelling was still to come. Still, the slapdash nature of the industry helped to keep it fast-paced and experimental. A particular hero’s powers might change wildly from one issue to the next largely because the writer hadn’t bothered to remember what he wrote in the previous script, but it also bespoke the “anything goes” energy of the Golden Age.

Comics were hugely popular in the ‘40s—over 90% of boys and girls in America read them (ask your grandma!)—but in the years following World War II, superheroes fell out of vogue in favor of other genres like horror, crime, and romance. It would take over a decade for them to come back in a big way, thus kicking off the Silver Age…but that’s a story for next time!

Looking to check out some Golden Age comics? DC’s got a few options if you want to read Superman’s earliest adventures, from the fancy-pants Superman: The Golden Age Omnibus (why yes, I would love it if you got me this for my birthday!) to the more affordable paperbacks Superman: The Golden Age or The Superman Chronicles, the latter of which reprints all Superman appearances in chronological order. Batman’s similarly represented with Batman: The Golden Age Omnibus, Batman: The Golden Age, and The Batman Chronicles. For my money, though, the most fun is to be had with The Wonder Woman Chronicles – Golden Age Wonder Woman is infamously, fabulously weird, and not to be missed.

Most of Marvel’s marquee characters wouldn’t show up until the Silver Age. The big exception is of course Captain America, who’s got his own fancy omnibus – Golden Age Captain America Omnibus – as well as the Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Captain America. You can also check out Namor, Marvel’s first superpowered star, in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Sub-Mariner, or read up on both Namor and the original android Human Torch in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Marvel Comics. Marvel gets additional props for actively courting female readers to make up for the postwar sales slump with female superheroes; check out the longest-running of those heroines, Venus, in—you guessed it—Marvel Masterworks: Atlas Era Venus.

The Golden Age wasn’t just what we now think of as the Big Two, though – the biggest seller during World War II was actually Fawcett Comics’ Captain Marvel. This version of Cap is now owned by DC due to a convoluted lawsuit and his Golden Age adventures aren’t reprinted super frequently, but you can find some of them in Shazam! A Celebration of 75 Years…or, since they’re now public domain, free and legal to download at The Digital Comic Museum. The DCM’s also a good source for another Golden Age standout now owned by DC, Jack Cole’s Plastic Man (then published by Quality Comics), one of the most inventive heroes of the time. Finally, Will Eisner was one of the first to take comics seriously as a budding artform. Read some of his landmark work on the Spirit (with the aforementioned caveat about Ebony White) in Will Eisner’s The Spirit: A Celebration of 75 Years, or again in the DCM’s Quality Comics collection.

If you’re interested in more non-fiction on the Golden Age, you can check out The Golden Age of DC Comics by Paul Levitz, or Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the Superhero by Danny Fingeroth. See you next time, when we biff-bam-pow our way into the Silver Age!

Comics of the era were also often crude, from a technical standpoint—although to be fair, even the finest art tends to degrade when printed on cheap newsprint, rolled up and shoved in some ten-year-old’s back pocket, and left in a warehouse for three quarters of a century. Stunning art could and did exist—Joe Shuster’s early work on Superman, C. C. Beck’s Captain Marvel, and Will Eisner’s Spirit spring to mind—but many of these comics were churned out at an incredible volume for low wages by would-be fine artists just trying to make ends meet until they could get more lucrative and respectable work in advertising. The idea of comics as a legitimate form of artistic expression and storytelling was still to come. Still, the slapdash nature of the industry helped to keep it fast-paced and experimental. A particular hero’s powers might change wildly from one issue to the next largely because the writer hadn’t bothered to remember what he wrote in the previous script, but it also bespoke the “anything goes” energy of the Golden Age.

Comics were hugely popular in the ‘40s—over 90% of boys and girls in America read them (ask your grandma!)—but in the years following World War II, superheroes fell out of vogue in favor of other genres like horror, crime, and romance. It would take over a decade for them to come back in a big way, thus kicking off the Silver Age…but that’s a story for next time!

Looking to check out some Golden Age comics? DC’s got a few options if you want to read Superman’s earliest adventures, from the fancy-pants Superman: The Golden Age Omnibus (why yes, I would love it if you got me this for my birthday!) to the more affordable paperbacks Superman: The Golden Age or The Superman Chronicles, the latter of which reprints all Superman appearances in chronological order. Batman’s similarly represented with Batman: The Golden Age Omnibus, Batman: The Golden Age, and The Batman Chronicles. For my money, though, the most fun is to be had with The Wonder Woman Chronicles – Golden Age Wonder Woman is infamously, fabulously weird, and not to be missed.

Most of Marvel’s marquee characters wouldn’t show up until the Silver Age. The big exception is of course Captain America, who’s got his own fancy omnibus – Golden Age Captain America Omnibus – as well as the Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Captain America. You can also check out Namor, Marvel’s first superpowered star, in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Sub-Mariner, or read up on both Namor and the original android Human Torch in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Marvel Comics. Marvel gets additional props for actively courting female readers to make up for the postwar sales slump with female superheroes; check out the longest-running of those heroines, Venus, in—you guessed it—Marvel Masterworks: Atlas Era Venus.

The Golden Age wasn’t just what we now think of as the Big Two, though – the biggest seller during World War II was actually Fawcett Comics’ Captain Marvel. This version of Cap is now owned by DC due to a convoluted lawsuit and his Golden Age adventures aren’t reprinted super frequently, but you can find some of them in Shazam! A Celebration of 75 Years…or, since they’re now public domain, free and legal to download at The Digital Comic Museum. The DCM’s also a good source for another Golden Age standout now owned by DC, Jack Cole’s Plastic Man (then published by Quality Comics), one of the most inventive heroes of the time. Finally, Will Eisner was one of the first to take comics seriously as a budding artform. Read some of his landmark work on the Spirit (with the aforementioned caveat about Ebony White) in Will Eisner’s The Spirit: A Celebration of 75 Years, or again in the DCM’s Quality Comics collection.

If you’re interested in more non-fiction on the Golden Age, you can check out The Golden Age of DC Comics by Paul Levitz, or Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the Superhero by Danny Fingeroth. See you next time, when we biff-bam-pow our way into the Silver Age!