True Crime: Rare Book Theft Edition

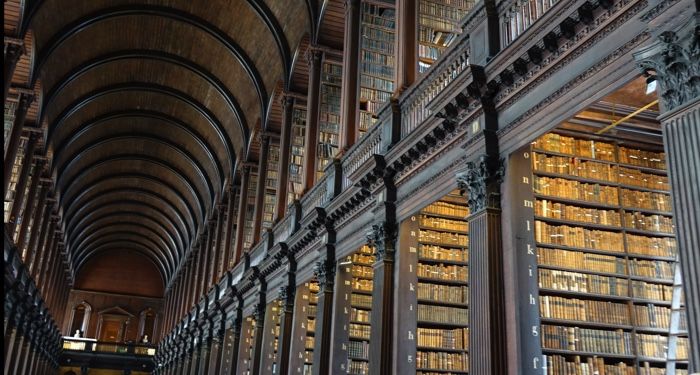

Books are unique objects. They are simultaneously a container of stories and knowledge while also being objects in their own right. Especially if a book is historical or rare, then it takes on its own significance as a valuable commodity and piece of art. And, like any beautiful object, that means some people will want to obtain it through illicit means.

While the most frequent type of book theft occurs when shoppers swipe current-release titles from bookstore or library shelves, rare and expensive books are also subject to being stolen. Often renowned for being first editions, their illustrations, or the fact that few copies exist of a certain title, these books can present a tempting target for thieves. Similar to stolen paintings, these books usually reappear on the illegal market or are hidden away for years by thieves who either want to use them as collateral in future, sticky situations, or who simply want to possess a rare object that no one else has. In these cases, the point is not to read the book but to possess or profit from it as an object of art, which is why these crimes are often investigated by art crimes divisions such as the FBI Art Crimes Team.

Art crimes involving books are cataloged in a variety of places, which can make it difficult to pin down exactly how many missing, valuable books are hidden away or being sold under the table. The International League of Antiquarian Booksellers maintains a Missing Books Register, where antiquarian booksellers can report missing items and also keep up to date on news regarding missing books. Databases like this can help create more awareness of crimes like the ones below, where valuable books were taken, and help booksellers and investigators work together for their safe return. Read on to find out about some notorious, bookish crimes.

The Transylvania University Caper

As a freshman at Transylvania University in Kentucky, Spencer Reinhard was taken on a tour of the school’s special collections library, where he glimpsed a copy of John James Audubon’s Birds of America. The book is treasured for its illustrations by Audubon, a renowned naturalist and painter, and the tour guide happened to mention that the school had recently sold a copy of the book for $12 million. This is when Reinhard’s mind began to formulate a plan. Along with his childhood friend Warren Lipka, who was semi-dropped out from the University of Kentucky and had a side business making fake IDs with another friend, Eric Borsuk, Reinhard began scheming to get the book and sell it on the black market — setting the friends up for quite the payday.

They eventually also recruited Charles Allen II, another high school classmate who was studying at the University of Kentucky and was lured into the scheme by the promise of a million-dollar take. The plan came to encompass several books beyond just Birds of America, including an 1859 first edition of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. The group began by laying the foundation for the heist by staking out foot traffic and staff patterns in the library, creating an alias with which to correspond with auction houses, and investigating the logistics of hidden bank accounts to store their payout.

In December 2004, they put their plan into action. Lipka and Borsuk entered the library and tasered librarian Betty Jean Gooch. Hastily grabbing their loot, they forgot to account for the fact that Birds of America is a large format book weighing over 50 pounds. When the thieves encountered an assistant librarian who gave chase, they dropped their prizes and made off with only smaller, less valuable works. Losing the Audobon works also meant they lost the interest of an illegal art market dealer in Amsterdam, who had originally agreed to buy the stolen goods. So, the group decided to take what they had stolen to Christie’s auction house in New York City for appraisal. It would prove to be a foolish mistake. In the rush to get the books appraised, Reinhard gave Christie his real phone number. The Lexington, Kentucky police, on the hunt for the stolen works, were able to easily trace it back to Reinhard at Transylvania University.

The four men were arrested in February 2005, and the books were found, unharmed, in a duffel bag. They pled guilty and received identical 87-month sentences. The four were released in 2012 and have gone on to speak in documentaries about, and even write books on, the heist and how it changed them. Reflecting on his actions, Borsuk commented that it was an awful experience but that he felt the fallout of the theft had ultimately made him a “better person.”

The Audubon Heist: ’70s Version

Reinhard and Borsuk were far from the first thieves to dream about selling off Audubon’s works to the highest bidder. In 1971, thieves smashed a window and broke into Schaffer Library at Union College in Schenectady, New York. They then proceeded to break the glass of a display case and ran off with their prize: a volume of Audubon’s Birds of America that had been bought by the college in 1844 and was on display for commencement weekend.

A few weeks after the theft, the FBI was contacted by antiquarian book dealer John Holmes Jenkins III from Austin, Texas. Jenkins had read about the theft and let the FBI know that he had been approached about purchasing a similar book to the one they were looking for after the robbery. Working with Jenkins, the FBI captured the thieves in a sting in a New York motel room and found the Audubon volume, along with other stolen works, in the trunk of a Chevy Impala parked outside. The thieves were arrested, and Jenkins was hailed as a hero who relished in telling his story for years to come.

However, Jenkins’s tale of himself as the savior of these books eventually came under scrutiny. In 2011, some digging by Union College’s alumni magazine found a connection between him and James S. Rizek, a dealer with a reputation for sketchy business practices. Rizek had previously been charged with defrauding libraries, and inspectors relooking at the case began to wonder if Jenkins had known about the provenance of the goods when he agreed to buy them or even if he and Rizek might have masterminded the theft in the first place.

This belief was echoed by one of the thieves, Kenneth Paull, who claimed that Jenkins knew the books were stolen and had turned on them. Unfortunately, the true nature of the heist may never come out. In April 1989, Jenkins was found in the Colorado River with a gunshot wound to the head. The justice of the peace ruled his death a homicide, but the local sheriff claimed it was a suicide and that Jenkins had become desperate as his debts and his own criminal dealings caught up to him.

The Iowa Book Bandit

One interesting theme in the annals of stolen book history is the cases where thieves wish not to profit from the books but simply to own and treasure them in their private collections. Such was the case of Stephen Carrie Blumberg, who was arrested in Ottumwa, Iowa, in 1990 and found to have almost 20,000 stolen books and manuscripts stashed in his house.

Blumberg had an interest in rare and old books from a young age, which was cited as an outgrowth of his interest in Victorian homes and architecture. Blumberg, who had come across the FBI’s radar throughout the 1980s for library theft, was a passionate reader who believed he was preserving books slated for potential destruction. His aim was never to profit from what he stole, as he believed that would be dishonest. Instead, he saw himself as building and stewarding a collection of rare books, and it was his aim to become the foremost rare book collector of his time, according to his accomplice.

Among the stolen volumes were a first-edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a 16th-century Bishop’s Bible, and a 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle that he claimed to have personally bound in ivory calfskin. When they raided his home, the FBI had to bring in a tractor-trailer to transport all of the books. Finding their rightful owners was somewhat of a logistical nightmare, as Blumberg had removed many of the ownership markings. Blumberg was convicted, sentenced, and then released, but unfortunately recommitted book thefts and was sent back to prison in 2004. While he was found guilty without reason of insanity, many of his family members and associates believed that mental health issues were at play in Blumberg’s compulsion to keep stealing books.

One common thread in each of these thefts is, unlike in a bank or jewelry store break-in, the robbers faced little resistance in either human or physical security. Libraries have, at the core of their mission, a duty to provide public access to their collections. Balancing this access with the need to protect rare and valuable items in their collections is a complex problem, especially if libraries do not have the funds to invest in technologies to help keep their collections secure. While book thieves might have a variety of motives that drive them, they are universally disrupting this right of public connection to texts. To find out more about notorious stolen books, check out our archives.