Put Translators on Book Covers

Translated literature is on the rise, which is wonderful — but we have to make sure we are honoring the translators who work on each book. Too often, translators are considered “invisible” contributors to the book, hidden on title pages or even in copyright sections. I’ve paged through a book trying to find its translator in its title page, back cover, everything, just to have to give up and find it online.

There are a few prominent translators who have managed to get more recognition, but they’re largely exceptions. Many of the exceptions are classic literature, largely because there are several different translations of these. For example, Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky are listed on the covers of their relatively new translations of Anna Karenina and War and Peace. But modern novels are left behind.

Ann Goldstein, translator of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, has some name recognition due to her role translating the international bestselling quartet, but she isn’t listed on the cover of the books. Do you know the names of Haruki Murakami’s translators? Jay Rubin translated The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Murakami’s first translator was Alfred Birnbaum, his most recent is Philip Gabriel. Those are just three of the people responsible for delivering his famous novels into the hands of English readers, and their names aren’t on the covers of his books.

Recently, translators have been pushing for better representation on book covers, and as a reader and reviewer, I have to agree. Translators must be listed on the front cover of the book, along with the author. Anything less is disingenuous and unfair.

As became apparent to many when the English dubbed version of Squid Game came out on Netflix in the U.S., translation is not an easy job. It takes a lot of time and effort by an individual or, often, a group of people working together, giving each other feedback, sharing notes. Translation’s nuances can be very complex. Translators have to make creative choices, from tone to syntax to how to deal with slang.

The smallest word or phrasing choice can have a big impact on the emotion that’s carried across. In some cases, you even need to change the phrase to match a cultural perception of emotion. Think about the difference between “I wasn’t given a choice” and “I had no choice,” between “I have a crush,” and “I like someone.” In some cases, they mean the same thing, but the implications are different.

In other words, every translated book we receive in English in the U.S. has been rewritten for us. A single person or team of people have taken a text in a language we didn’t understand, and translated each word, each sentence, each paragraph, into English. A directly literal translation is basically never satisfying, so each translation has been carefully considered, and made readable in ways that consider cultural context, slang, emotional resonance, and connotations.

It’s a miraculous feat! Anyone who has had to translate a single sentence in a language class should know how impossible it feels. Every translator has poured their heart and soul into the book they translated, and they should receive credit alongside the author.

Think of it this way: there are actually two books. There’s — for example — Män som hatar kvinnor by Stieg Larsson, and there’s The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Laarsson, translated by Reg Keeland. They’re different books. They may have different word counts. They have literally different titles, as the Swedish title translates literally to “Men who hate women.” Every time a book is translated, there are then two texts in the world: the original by just the author, and the translation by the author and the translator.

I should note that my copy of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, this incredible international bestseller, does not list its translator, Reg Keeland, on its front cover. And that highlights the problem. Keeland was a crucial author of the English manuscript, but his name is nowhere in our sights. American readers could pick up this book without knowing it’s been translated.

And perhaps marketing teams in publishing houses think this is better. They might think that more books will sell, because Americans and the people of the UK will be less likely to pick up translated works. After all, we’re extremely English-centric countries. And people tend to assume, for some reason, that translated work is automatically more literary, or stiff.

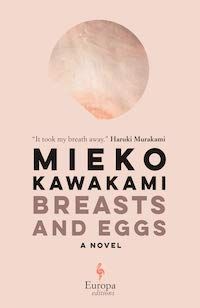

But how are we supposed to break those perceptions if books like Dragon Tattoo don’t have their translators listed on the cover? When I was a kid, I read Inkheart by Cornelia Funke — were you aware that it was a translation from German by Anthea Bell? I wasn’t. It wasn’t on the cover. Teams of translators should also be acknowledged. For example, the award-winning book Breasts and Eggs by Mieko Kawakami, a 2020 Time Best Novel of the Year and New York Times Notable Book of 2020, was translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd. But you wouldn’t know that by looking at the cover.

This all matters beyond the realm of simple fairness. There are too few books available in English translation from around the world. There is a wealth of international literature that English readers can’t access because there isn’t enough funding for translations or support for translators.

Recognition can support translators and reinforce their place in the literary world: they cannot be buried as a footnote if their name is recorded on the cover of their book. If the book wins an award, and the trophy and the cover and the listing all include the translator’s name, that recognition is extended.

Through many other channels, we’ve seen that recognition and awareness can support concrete changes, and I firmly believe that raising general awareness of the prominence and importance of translators is not just symbolic. There was a lot of publicity around the poor translations of Squid Game, but Netflix only actually spent $6,305 on translating the show, even though the show made almost a billion dollars. Translators deserve better than that. Vastly better.

By placing their names beside those of the authors, publishers would also be forced to recognize their crucial role in giving us a text. This rise in respect could support the field as it fights for better pay, royalties, and more in the future. The more we celebrate translation, the more books we’ll be able to get in translation, because publishers will see that they sell and they matter.

So what can you do to help? First, read books in translation, and when you share your love for them, include the name of the translator. Call out publishers who have not included the translators on their covers, using the hashtag #TranslatorsOnTheCover. Do you have favorite books that were translated, and you remember the author but not the translator? Fix that — look it up, and then follow the translator on social media, or look up what else they’ve worked on.

And let them know you love their work! For example: I love the work of translators Megan McDowell (Things We Lost in the Fire, Fever Dream) and Tina A. Kover (Disoriental, A Beast in Paradise). Shout it from the rooftops! Share your love of their work right alongside the work of the authors. Don’t let the names of translators be buried anymore.