Translate Émile Zola: An Open Letter to Publishers

Artists, coal miners, prostitutes, politicians: you’ll find all of these characters and more in the works of Émile Zola.

I read my first Zola novel in college, during a lull in my final exams at the end of sophomore year. The college bookstore happened to have a copy of Le ventre de Paris (The Belly Of Paris) in its little “general literature” section, and from the moment I read the first page I was HOOKED.

Setting out to write about every aspect of French society under the Second Empire, Zola (1840-1902) crafted twenty exquisitely detailed novels over the course of two decades at the end of the 19th century. His formulation of literary Naturalism, where the writer attempts to objectively study and analyze human society through the lives of his/her characters, was so influential that it drove Stephen Crane, Frank Norris, and Theodore Dreiser, among others, to craft their own versions of American Naturalism.

Zola believed that the novel should dive below the surface of everyday life, revealing the dirt, gossip, waste, greed, hostility, and bitterness that other writers refused to acknowledge. Inspired by the discussions of human evolution and natural selection raging around the western world at the time, Zola wanted to use literature to expose and acknowledge the animal in all of us, the most basic instincts that still drive us no matter how “civilized” we attempt to be. He saw himself as a student of human behavior, and subsequently left a remarkable chronicle of one nation on the cusp of enormous change.

His magnum opus, The Rougon-Macquart: the Natural and Social History of a Family under the Second Empire (1871-93), follows the offspring of two families over a period of twenty years (1851-1870), enabling Zola to explore the lives of such people in French society as coal miners, department store managers, painters, politicians, priests, slum-dwellers, and prostitutes.

And now a few reasons for why I wrote this post. My search for a standardized, modern, English-language edition of Les Rougon-Macquart turned up no such thing. However, I did find a few helpful websites devoted to the works of Zola, particularly the Rougon-Macquart series (all in various stages of development): Reading Zola (ongoing and also the most comprehensive), The R-M Novels of Emile Zola, and The R-M by Emile Zola). Here you’ll find plot summaries, analysis, relevant chronology, historical and political contexts, and other Zola-y things.

All of these sites also note that you can find most of the R-M novels in English translation at Project Gutenberg. Now, as you all know, I’m not a print-snob, and I’m not saying that a digitized Zola is less wonderful than a print Zola. What I am saying here is that I do mostly read print books and my house is groaning with over 700 of them (so far- hee hee!). And I’m one of those people who drools over “The Collected Works of…” kinds of things. I luuuuuuurve symmetry, consistency, standardized stuff- you get the idea. So all I’m asking is this one teeny-tiny-itsy-bitsy thing:

Somebody, ANYBODY, translate the entire Rougon-Macquart series into English and sell it as a set with beautiful impressionist paintings on the covers please and thank you.

Now, I do know that Oxford University Press has been bringing out many R-M novels with new translations over the past decade, but I am greedy and want it ALL. So, if OUP is actually planning to do the whole shebang, that’s awesome, but until then…

I hear you, publishers of translated fiction: you’re saying that this is easier said than done, and I completely understand. This project would take years and many dollars and many dedicated people. I’m just trying to get the ball rolling.

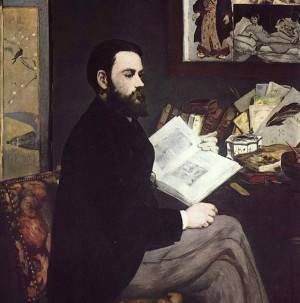

To that end, I’ve done some front-end work for you! Below is a list of all 20 of the Rougon-Macquart books in order of publication along with a relevant painting by Edouard Manet. Manet is perfect for so many reasons, including the fact that he, like Zola, depicted men and women from all classes and walks of life, and Manet was at his most experimental just as Zola was cranking out the R-M novels. Oh, and Manet painted Zola’s portrait this one time (see below).

Anyway, if you’re still reading, you’re in for a treat: 20 fan-freakin-gorgeous Manet paintings and one-sentence summaries of each R-M novel.

And remember to tell us in the comments which Zola novels you’ve read!

La fortune des Rougon (1871)

Introduces the reader to many of the characters in the series and sets them against the backdrop of political upheaval following the coup d’état of Louis-Napoleon in December 1851.

La curée (The Kill, 1871-2)

A scathing portrait of the middle-class that brings into relief its lust for money and pleasure in an age of decadence.

Le ventre de Paris (The Belly of Paris, 1873)

Features Les Halles, a vast, roofed meat and produce market, and a man whose struggle against the coup d’état acts as a constant rebuke to the reforms of the Second Empire.

La conquête de Plassans (The Conquest of Plassans, 1874)

This is the story of a politically-minded priest, a woman’s psychological collapse, and apparently one heck of a shocking ending.

La faute de l’Abbé Mouret (Father Mouret’s Transgression, 1875)

A surrealistic novel set near Plassans that focuses on a priest who, worn down by illness and intense devotion, falls under the care of an Eve-like figure.

Son Excellence Eugéne Rougon (1876)

In which the eponymous character, once a powerful government minister, plans his return to power with the help of an Italian adventuress.

L’assomoir (The Dram Shop, 1877)

The depressing and gritty story of a working-class laundress who, despite wanting to improve her circumstances, ultimately destroys herself with the help of her husband, her ex-husband, and large quantities of alcohol.

Une page d’amour (A Love Story, 1878)

A lonely woman dealing with her daughter’s neurological problems, a doctor who tries to help, and the love that blossoms between them (but this is Naturalism so don’t get your hopes up).

Nana (1880)

Having escaped a life of brutality and neglect (see L’assommoir), Nana becomes a popular Parisian courtesan, bleeding dry her many rich conquests and basically taking Paris by storm, that is, until she destroys herself through excess.

Pot-Bouille (Pot-luck, 1882)

A massive tragi-farce, Pot-Bouille details the rise of Octave Mouret to become the head of “Au bonheur des dames,” making it the largest department store in Paris and enriching himself through affairs and some wheeling-and-dealing.

Au bonheur des dames (The Ladies’ Paradise, 1883)

A detailed, complex exploration of the rise of the modern department store and how it sucked the life out of smaller retail shops, set against an improbable love story.

La joie de vivre (The Joys of Living, 1884)

A bleak story of an orphaned girl whose guardians spend her inheritance and blame her for their problems.

Germinal (1885)

A powerful tale of coal miners who strike in order to change the terrible conditions under which they must work.

L’oeuvre (The Masterpiece, 1886)

Based partly on the experiences of Cezanne, L’oeuvre chronicles the life of a brilliant but emotionally-overwrought painter who helps usher in a new era of art but ultimately cannot complete his work or settle down into a stable family life.

La terre (The Earth, 1887)

Described as both a positive portrayal of peasant life and a searing criticism of the same, La Terre delves into land-rights issues and their political ramifications.

Le rêve (The Dream, 1888)

Focuses on an orphaned girl (again) who falls in love with a nobleman, and all the strongly-held religious beliefs and traditions that conspire (through the nobleman’s father) to keep them apart.

La bête humaine (The Human Beast, 1890)

A violent story of sex and murder, this particular novel delves deep into the psyche of a young man abandoned by his mother in the countryside and his ultimate rage against women and loss of control.

L’argent (Money, 1891)

A satire of the Crédit Mobilier scandal of the 1870s, L’argent portrays the financial machinations of a man who is blind to everything but the acquisition of wealth.

Le débâcle (The Debacle, 1892)

A scathing but objective look at France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War through the story of two soldiers who bond in the field and then during the bloody days of the Paris Commune.

Le docteur Pascal (1893)

The novel that brings the entire cycle home, in which Zola depicts himself as “Doctor Pascal,” a member of the Rougon-Macquart family whose genealogical research has shown him the patchwork of greed, violence, and cruelty of his forebears, even as it ends on a note of hope for future generations.