The Roald Dahl Survival Guide For Kids

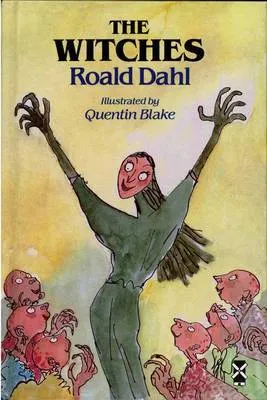

Only two books have been so good to demand insomnia of me until they were completed. One was The Great Gatsby. I know, how boring and predictable. The other is not so obvious, but no less hypnotic – The Witches by Roald Dahl.

Dahl’s narcotic effect came to mind after reading the list of the 100 greatest kids books, brought to us this month courtesy of Parent & Child Magazine. And there was only one Dahl book (Matilda) in there. At 41. ONE! AT 41! I was so shocked my inner caps lock jammed.

You will be relieved to hear this is a post less about the failings of this poll (bemoaning such lists is like cursing election results in Russia – the futile pursuit of the damned) and more about reminding myself why my yet-to-be-born kids will probably have the complete collection of Roald Dahl books before they get a cot.

You may think I am joking, but Dahl has plenty of useful lessons for kids. For instance, he taught me early on that families are unhinged carnivals that dance alongside our lives – places where magical and terrible things can happen within the same heartbeat. There is more where that came from.

I am not sure how deeply engrained Dahl’s books are in the average childhood beyond the UK – the paltry showing in the US-based Parent & Child poll suggests they are not – so for your delectation, here are a few life lessons gleaned from Dahl’s books:

Adults will ignore/abandon/abuse/kill you.

The majority of Dahl’s books are written from the point of view of children. From where they are standing, adults are the most horrible creatures on the earth. Especially if you are related to them. Matilda’s parents are petty crooks who actively ignore her special gifts. In George’s Marvellous Medicine, his gran is anything but. She starts out mean and then becomes a monster. James, of James and the Giant Peach fame, is enslaved by his nasty aunts. Plus Dahl also wrote the script of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and therefore created childhood’s most terrifying nemesis – the child catcher. Who needs national ad campaigns warning of ‘Stranger Danger’ when you have a generation weaned on Roald Dahl?

Animals have it sorted.

The only functioning family units Dahl gives us are of the furry or arachnid kind. Fantastic Mr Fox is not only worthy of that title for the way he fools the evil farmers, but for making raiding the chicken coop a fun activity for his whole family. And in James and the Giant Peach, it is the oversized insects within the massive fruit that give him the family life that death and cruelty, two facets of the adult world according to Dahl, denied him. Is it any wonder that the boy in The Witches chooses to remain a mouse, and live a much shorter life, than become human again?

Your vices will destroy you.

One thing Dahl understood better than almost any other children’s writer in the last century is that kids are deeply unsentimental. Witness their casual cruelty to one another, their delight in the dark and nasty, and their untuned moral compasses. Yes, Dahl has a firm sense of good and evil, but he is no way as prescriptive about it as, say, C.S. Lewis. Even his good characters get to do terrible, awful things. George systematically poisons his grandmother. In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Willy Wonka blithely allows his children visitors to be mutilated. Matilda torments her teacher via telekinesis. James’ new insect family crush his aunts. But all these acts are justified via a certain kind of Old Testament logic – their meanness brought their doom upon themselves – and are played out like a Tex Avery cartoon.

With all this being fed to us from birth, it is amazing the UK hasn’t turned into a place full of distrustful people who love animals and relish saying ‘I told you so’. Oh, wait…