Sympathy for the Trees and Empathy in Children’s Books

This is a guest post from Kristen Twardowski. Kristen stumbled her way through working with wolves and libraries and has finally found her professional home doing marketing and data analysis in the publishing industry. Though there will always be a place in her heart for numbers and graphs, the rest of her love is given to books.

You can find her at: https://kristentwardowski.

Many people describe The Lorax with its Truffula Trees and warnings about the dangers of deforestation as their environmental awakening. As children, they read Dr. Seuss’s work and discovered that what people do affects the world around them, sometimes irrevocably.

My introduction to the delicate balance of nature, however, was a little different. Mine involved a dragon, a unicorn, and the daughter of a king. And if that doesn’t sound like the beginning of a very odd joke, I don’t know what does.

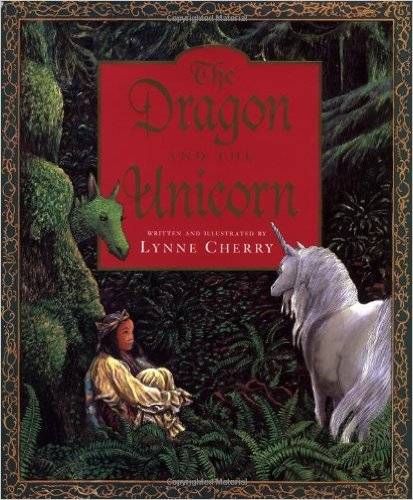

The book that changed my perspective was Lynne Cherry’s The Dragon and the Unicorn. In it, Arianna, the daughter of a king, becomes lost in the forest that her father has been mining for resources. While there, a dragon and a unicorn show her the wonders of their home. Arianna also sees the results of her father’s destructive tendencies. Through Arianna’s eyes, the reader not only feels empathy for the creatures of the forest but also begins to understand that abusing the forest will have repercussions. If Arianna’s father demolishes the trees instead of finding a renewable way to deal with the forest’s wealth, his kingdom will begin to suffer.

The book that changed my perspective was Lynne Cherry’s The Dragon and the Unicorn. In it, Arianna, the daughter of a king, becomes lost in the forest that her father has been mining for resources. While there, a dragon and a unicorn show her the wonders of their home. Arianna also sees the results of her father’s destructive tendencies. Through Arianna’s eyes, the reader not only feels empathy for the creatures of the forest but also begins to understand that abusing the forest will have repercussions. If Arianna’s father demolishes the trees instead of finding a renewable way to deal with the forest’s wealth, his kingdom will begin to suffer.

So I read The Dragon and the Unicorn, and I worried about the wilderness. I also worried about the fate of the animals. Where would the dragon and the unicorn sleep, I wondered, if the trees disappeared? How could they have their picnics of blueberries and strawberries if bushes stopped bearing fruit? How would they breathe if smoke filled the air? It turns out that I was not the only child whose concern for animals formed her relationship with the natural world.

Fiction allows children to identify with the world around them. Books, even ones with fantastical creatures, allow children who may not have direct contact with nature to learn to appreciate wildlife. According to the U.S. Census, over 80% of the U.S. population lives in urban areas, and a not insignificant portion of those people are children. Though some of those kids may have the chance to visit wild spaces, many others do not. Pigeons notwithstanding, they never have the chance to stumble across animals in their natural habitats. Their relationships to the natural world are based on the media they consume. If they read books about the environment, it changes how they think. And often they want to do something to protect it.

Professor of Education Daniel Holm describes this as “environmental empathy in action.” When individuals like nature, they fight for it. This could involve cleaning up litter from the side of the road or making sure that sea turtle hatchlings succeed in their long walk towards the ocean. In creating this environmental empathy, the fantastical nature of books like The Lorax and The Dragon and the Unicorn produces people who work to make their world a better place.

With recent threats to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and discussions about climate change, cultivating empathy for the environment is becoming increasingly vital. As the Lorax would say, someone has to “speak for the trees.” Why shouldn’t children be the ones to speak? But until we can convince a dragon or a unicorn to tour elementary schools, encouraging kids to read books about nature may be the best way to create a future filled with environmental empathy.

(Though if you know a fantastical creature who would be up to talking with children, send them may way. I’m happy to arrange something.)