Getting the Job Done: Superheroes and the Immigrant Experience

Superheroes have been used, interpreted, and misinterpreted as a metaphor for just about everything. One of the most enduring comparisons is the superhero as immigrant. Superman, as he is with so many things, remains the standard bearer of this idea, but he’s hardly alone. That sense of (sometimes literal) alienation, of having to hide parts of who you are to protect yourself and loved ones from those who don’t understand, is painfully familiar for many superheroes — as it is for many immigrants and their children.

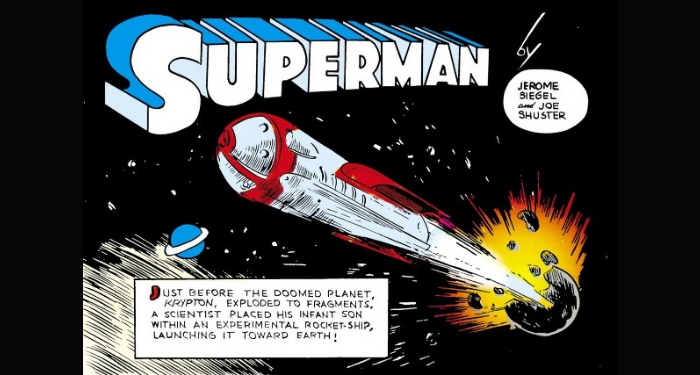

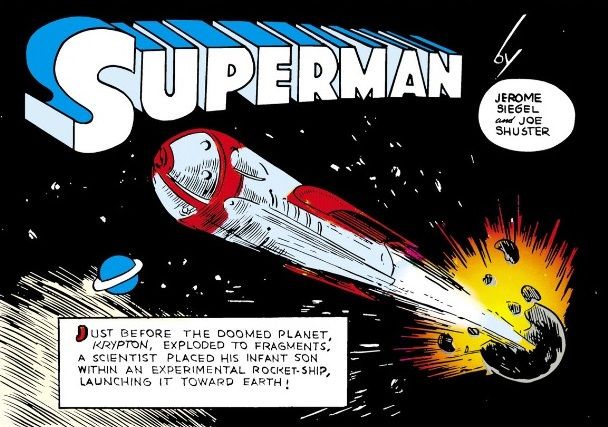

And of course, there is the obvious: a child whose homeland/home world is no longer stable or safe. Desperate parents who send that child to another place, hoping their beloved son will find shelter out there in the unknown. The boy who, despite not always fitting in, survives and thrives in his adopted world, taking advantage of the great opportunity it offers to excel beyond everyone’s wildest dreams.

Okay, so not all immigrants can be superpeople, nor should their worth as human beings be based on whether or not they are superhumanly good at something, or even whether they have the right set of papers. (Superman, as Lois Lane and others have said, is himself undocumented.) The point is, Superman’s experiences can very easily be seen as an allegory of the immigrant experience. There’s a reason for that.

Alex Segura’s Secret Identity, a thrilling murder mystery set in the 1970s, is one of the latest texts to discuss this allegory. His main character, Carmen Valdez, is a Cuban American immigrant who grew up loving comics — she even used them to help her learn English. As an adult, she makes her way from Miami to New York to work for the fictional Triumph Comics, where her status as an immigrant woman of color is just one of many obstacles that bar her from becoming the comic book writer she has always dreamed of being.

Don’t worry: I won’t be spoiling the book here. Instead, I talked with Segura about how he developed Carmen’s character, the themes of immigration threaded throughout the story (and comic book history in general), and how his own experiences as a Cuban American influence his works.

Where Do Superheroes Come From?

The nascent comic book industry was awash with immigrants and the children of immigrants. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, creators of Superman, were the sons of European Jewish families, and Shuster himself moved from Canada to the U.S. as a child. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, creators of Marvel as we know it, were also born to European Jewish immigrants. Alex Toth was of Slovak-Hungarian descent, and Will Eisner’s father was from what is now Ukraine. And the list goes on.

This proliferation of immigrant talent was not due to any special fondness for comics. As a character in Secret Identity bluntly puts it, “It’s comics, girl. People crank these out like pizzas. You think anyone is trying to produce high art?”

Many of the real-life writers and artists working on comics felt the same, but their ethnicity and/or lack of resources kept them from entering more reputable industries. As artist Nick Cardy explained in David Hajdu’s The Ten-Cent Plague, his first choice was to be a fine artist, and his second choice was to be an illustrator. He could not afford to do either — and, given that he was an Italian American with the birth name Nicholas Viscardi, he probably wouldn’t have been able to find employment there anyway. Fortunately, he quickly grew to like comics, a field he only entered out of financial desperation.

Segura pays subtle homage to the immigrant origins of comics with the character Doug Detmer. Detmer is a past-his-prime artist of incomparable influence and talent, drawing frequent comparisons to Kirby, Toth, and other early industry legends. While his ethnicity is only hinted at, Segura confirmed it when I asked.

“Yes, in my mind Detmer was akin to Kirby and that era of creators,” he said. “I envisioned him as the Jewish child of Eastern European immigrants, though we don’t get into that level of detail in the novel…I saw him as more of a contemporary of that older generation, who imbued his art and stories with echoes of his own family’s immigrant experience.”

And then, of course, there is Carmen Valdez, part of a new generation of comic creators. By the time she enters the industry, many of those early immigrant and first-generation creators had been pushed out for a number of reasons. One of those reasons was, ironically, an immigrant: Fredric Wertham (born Frederic Wertheimer) was a German-born psychiatrist who railed against superhero comics. While some modern observers see Superman as a symbol of the immigrant experience, Wertham saw only a lawless fascist and helped to orchestrate a massive backlash against comic books.

With comics looking whiter and less diverse than ever, Carmen is an outsider in an industry that should have welcomed her with open arms.

Parallel Worlds

Anyone who does any type of creative work knows how a creator’s real life and experiences bleed into their work. This happens whether you intend it or not, whether you’re writing about something that actually happened to you or not. It affects everything about your work, from your choice of subject to how you execute that subject.

Case in point: this article. I don’t know as I would have latched onto this secondary theme in Segura’s novel if my own father was not an immigrant.

Secret Identity is another prime example. Segura told me about how much of himself he put into Carmen’s “origin story” — for example, each discovered comics at a young age, and buying comics became both an opportunity to bond with their fathers and an educational experience.

“I learned so much about the world and American culture outside of my mainly Cuban American Miami bubble from comics,” he said. “It was an unforgettable education and I wanted to reflect that a bit in Carmen’s story.”

Segura also told me that he makes a point of including pieces of his own history and culture in his works whenever he can: “Everything I write touches on being Cuban-American and my background, because it’s such an important part of who I am and who my family is.”

Why is this so important for Segura? “As a kid, I didn’t really see people like me in books, TV, or comics, and I really wanted to try and do what I could to tip those scales,” he told me. “There’s so much to be said about recognizing yourself in the characters you read about, and I hope that readers who share that background can see themselves in these characters.”

This was not an option for the early immigrant creators. No way would mainstream America have embraced a superhero who went to synagogue or an Italian American saving the day. But that doesn’t mean these creators didn’t put just as much of themselves into their characters as Segura does with his own.

Secret’s Out

Despite limitations and cultural pressures, immigrant and first generation creators still found ways to infuse comics with bits and pieces of themselves. As Brad Ricca put it in his Siegel and Shuster biography Super Boys, “The work: that is their secret identity.”

Many superheroes started punching Nazis well before America entered World War II because Hitler was targeting Jews, and Jewish comic creators felt compelled to make a statement. (This was no small thing: both Kirby and Siegel received threats for their anti-Nazi comics.) Jack Kirby based the character of the Thing on himself, to include references to a hardscrabble childhood in the Lower East Side. Siegel and Shuster remained fairly secretive about their inspirations for Superman, but he was probably cobbled together from many elements, including European-born circus strongmen, the story of Moses, and folkloric tales of the protective golem, among others.

In Secret Identity, Carmen Valdez co-creates a superhero, the Lynx. Like her real-life predecessors, Carmen can’t just come out and create a character who looks like her. Nevertheless, she imbues the Lynx with the dreams, morals, and values that are her inheritance as an immigrant. The novel describes her work as having “a theme — of an outsider trying to find justice, trying to reclaim an identity and legacy that had long been denied.”

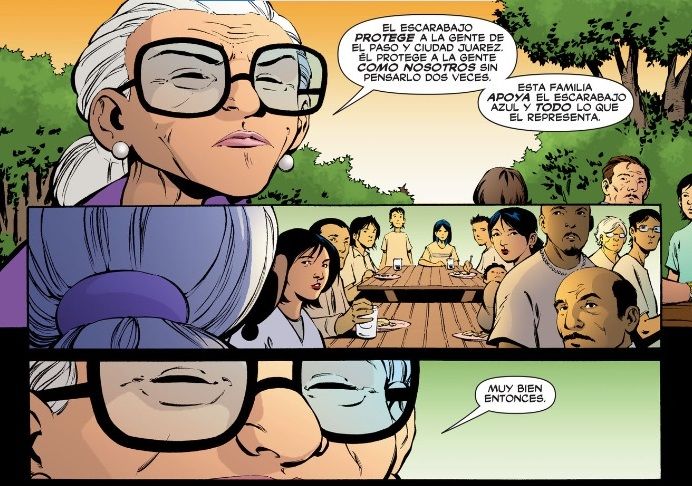

Nowadays comics, while imperfect, are allowed to depict a much broader range of human experience. This includes the immigrant experience. It’s now been established Captain America’s parents were Irish immigrants. And we have newer characters like Jaime Reyes, who lives on the U.S.-Mexico border and protects people on both sides as Blue Beetle, and Kamala Khan, whose relationship with her Pakistani parents and culture is a key part of her journey to becoming Ms. Marvel.

So, while Carmen’s world of the 1970s isn’t always welcoming to people like her, the world of the 2020s is a natural time for her story to be published. The immigrant experience may not be the overarching theme of Secret Identity, but, like early comics, it is always within reach, easily spotted by anyone who cares to look.