STRANGERS IN PARADISE and the Audacity of Love

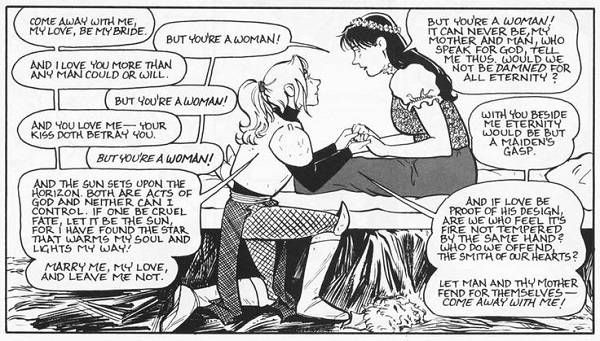

Growing up in the ’90s, I fully bought into the idea that reality did indeed bite and that anything that reeked of enthusiasm or sincerity was hollow. Sarcasm was a sign of intelligence and apathy was a valid repudiation of anything that might veer towards the maudlin. Anything even resembling an attempt at romance was met with a scoff and dismissal that it was greeting card level sentimentalism. But then Strangers in Paradise comes into your life and ruins everything. Terry Moore’s landmark work has the audacity to celebrate the idea of love.

If for some reason you’re unfamiliar with Strangers in Paradise, it’s Moore’s ’90-issue story that began in 1993 of two women, Francine and Katchoo, adrift in a crime thriller sea and the tumultuous waves of deep romantic connection. You’ll occasionally see it described as a “slice of life” work and that’s not really accurate, but there’s no denying the core of the series absolutely presents one of the most affecting looks at, not just homoromantic love, but love as something bigger and far more universal. I don’t say that lightly or in a manner that erases what is inextricably linked to sexuality, specifically Katchoo’s very open queer identity and Francie’s journey to discover her own sexual orientation. Rather, as these two characters navigate the ever-winding road of attempting to discover precisely what it is they truly want and who they are, there’s always the tether point of undeniable love tethering them to each other. It’s a pure love that often transcends physical attraction and centers itself on the two of them knowing little else other that they want to be as emotionally close to each other as two people can be. It’s pure. It’s simple. They love each other. They’ll figure out the rest as they go along.

Of course, “figuring it out” is messy as all hell. Katchoo makes no secret about her deep romantic attraction to her best friend and Francine’s “traditional” religious upbringing, replete with dreams of marrying Mr. Right and having children, and insecurities make her constantly unsure about going all-in with Katchoo. Francine may not be sure that she loves women, but she is unshakably sure that she loves this woman. Throw in some mafia drama, mysterious figures from the past, and, oh yeah, a love triangle with the introduction of maddeningly gentle and sweet art student, David, and you’ve got a mess something fierce. It’s those elements, however, that make the story accessible, especially to a cynical adolescent used to scoffing at anything that dares to express sincerity. Well, those, and the fact that Katchoo is a perfect storm of sass, anger, and vulnerability akin to Rayanne Graff – shout out to my My So-Called Life peoples!

About midway through the series, there’s some metacommentary about the repetitive nature of its own story. It’s a cycle, a series of differing circumstances all trying to move over the same final hump. There’s this central conceit throughout of finding “home” in another person, of seeing your center in another, and how insanely comforting and scary that is. Of course it’s messy and scary; that level of vulnerability is going to incite all sorts of irrational behavior. That’s because Moore continually highlights that love isn’t rational and we see opposite extremes of this in Katchoo’s overly aggressive behavior and Francine’s emotional retreats. Every time something is resolved a new obstacle props itself up, challenging what ultimately reveals itself as the unchallengeable: their love of each other. It’s a beautiful madness of fluctuating, sometimes repetitive behaviors and sentiments because emotions are not domesticated animals and because relationships are complicated – insert clapping emojis wherever you deem fit. What’s more complicated and relatable than knowing what you want and not knowing what you want at the exact same time?

There’s a lot more nuance to the story than what I’ve just laid out here, to be sure. Every character is worth a thesis-level examination on their own and the way Moore incorporates genre trappings and comic book industry elbowing is great when paired with his absolutely masterful cartooning. It’s important to note that the work is definitely not without its problems, especially to the modern eye, as wonderfully examined in this piece by Arnar Heidmar for Women Write About Comics. However, at the time I first discovered Strangers in Paradise, and the revisiting I’ve done since, the sheer fearless embrace of love not as a corny fairy tale emotion, but as an ideal, as an achievable and undeniable force, that always beats that immature “too cool for school” attitude to a blubbery mess.

I’ve largely danced around too many specifics, so that if you haven’t read it you’ll be enticed to, or if you have, you know what I’m talking about and maybe go back and give it a re-read. Maybe it won’t or doesn’t speak to you on the same level. That’s cool. Strangers in Paradise doesn’t re-write the book of love and I wouldn’t go so far as to say that it’s “unlike anything else!” in full-blurb fury, but I’d also argue that it isn’t trying to. In fact, that’s exactly the point. Moore paints love as the reality we know it can be, whatever the complicated details may be. The work has the nerve to laud and lay bare love as truth, incorporeal yet substantial. In this time where it feels like every day brings on some sort of new awful nightmare and they very notion of love seems like too much of a fairy tale, Strangers in Paradise can remind as much as it comforts, that some dreams are stronger than reality.

Strangers in Paradise is returning in 2018. You can find it and all other Terry Moore work at abstractstudiocomics.com.