Stories of the Impossible – An interview with Patrick Ness

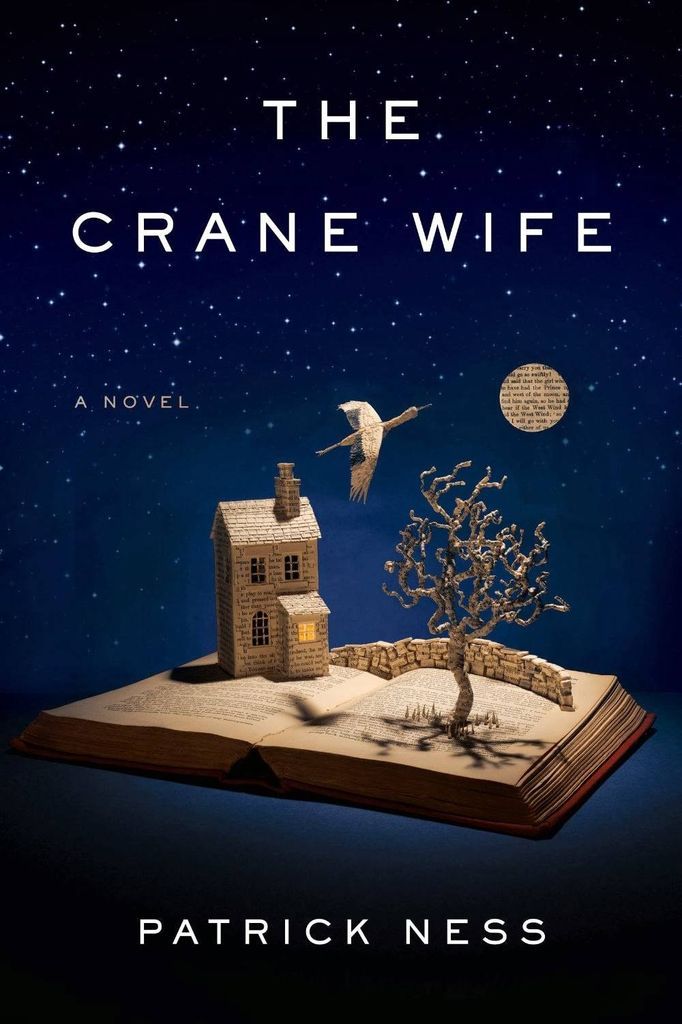

According to Patrick Ness, the extraordinary happens every day. Not only is it a handy subheading for his new book, The Crane Wife, but it is also a credo to live by. A tweak in perspective and the mundane can become magical.

According to Patrick Ness, the extraordinary happens every day. Not only is it a handy subheading for his new book, The Crane Wife, but it is also a credo to live by. A tweak in perspective and the mundane can become magical.

The Crane Wife sucks you into Ness’ world view. It tells the story of George Duncan, a likeable if unexceptional man, who finds a wounded crane in his back garden. An arrow has pierced its wing. George helps the crane before it flies off. The next day he meets the mysterious Kumiko. They fall in love and start making works of art from books, so beautiful they reduce anyone who sees them to tears.

The story is an adaptation of an ancient Japanese folk tale, updated and set in contemporary London. While the myth was clear that the woman and the crane are the same being, The Crane Wife is deliberately hazy about Kumiko’s background.

For Ness, the book is a return to adult fiction after more than a decade spent conquering the world of young adult fiction with the acclaimed Chaos Walking series.

The US-born, London-based author caught up with Book Riot during the Edinburgh International Book Festival to share his thoughts on the difference between YA and adult fiction, nuisance cyclists, and where stories really come from.

We all grow up surrounded by myths and fairy tales, from the legends of ancient Greece to the Grimm Brothers. So what drew you to this obscure – in the West, at least – Japanese myth about the crane wife?

I had the idea for a long time. I like the idea of stories based on myths. Stories that has lasted a thousand years are myths for a reason. They have applications and variations. This one felt private. It felt mine.

My kindergarten teacher was Japanese-American. I loved her, loved her. I was in love with her – as you are when you’re five. I heard the story of the crane wife then. And again. And again. It was always there. I could feel I was responding to something.

And then I got the other ideas contained within the book. A major one is how a story is different depending on who tells it. And that stories are vitally important, but they’re not everything. They have a function, but they are not everything.

So these two ideas went together. And then I heard The Decemberists’ song, The Crane Wife 1, and it was perfect. It was exactly how I imagined it feeling. I pick theme songs for my books not because I’m writing about the song, but because the song makes me feel how I want my readers to feel. And The Crane Wife 1 is exactly it. It was the icing on the cake. That was it, I was ready.

I also knew the last line of The Crane Wife. That’s so important, how you leave a book. It is so, so, so vitally important. I don’t start until I know my last line.

What other songs have you used to set the mood of your books?

Mercy Street by Peter Gabriel was A Monster Calls. It’s a beautiful, atmospheric song about a poet. The song doesn’t pertain to the book, but the emotions and the atmosphere does.

The Chaos Walking series had one for each. The first one, The Knife of Never Letting Go, was a Muse song, Map of the Problematique. That’s a good running song, a yearning song. I wanted that feeling of yearning and energy.

And More Than This is named after a Peter Gabriel song. Not the Roxy Music Song. Not the One Direction song. The first lines of that song are, “I woke up and the world outside was dark”. Now, that is a great opening line to a novel. I didn’t use it, but it just made it the perfect theme song.

How much of the opinions shared in The Crane Wife reflect your own? For example, Amanda, George’s daughter, rages at cyclists and their “crotch-fitting tights and their air of ethical entitlement”. Where does Amanda’s opinion end and yours begin?

[Laughs] Amanda is great because she says all the stuff that you know you shouldn’t say. There’s a bit where she’s particularly vicious about Australians. I am not against Australians, but I did that for a reason. She knows it’s wrong. But, as she says, isn’t ‘wrong’ sometimes thrilling? That’s why it’s in there. It’s a taboo. She doesn’t believe it, but does only at that moment when you’re angry. It’s fun to write.

Let’s say I’m pretty agnostic on cyclists.

I am opposed to the Animals in War Memorial. [In the novel Amanda says: “It’s an insult to the actual men and women, actual fathers and sons and mothers and daughters who died in war to equate them with a f*cking Labrador”] I think its a huge waste of money. There are children starving in the world and we have this.

What about the contemporary art scene? Their response to George and Kumiko’s work is rather pretentious.

Oh that’s gentle satire. There’s a lot of nonsense in contemporary art, but there is some that is breathtaking. I saw the Rachel Whiteread’s doll houses; they are beautiful. You don’t know why it works, why it touches you, but it does. And Antony Gormley, when he had all the figures on the rooftops in London. And when you stood on the balcony of the Haywood Gallery, they were all looking at you. You were in the centre of this vast circle and it was amazing.

When people in the book encounter the artworks, their reaction and feelings are articulated in detail. What they are actually looking at – the art – less so. Is there a danger that if you describe the works too clearly they’ll fall short of the supposed response?

When people in the book encounter the artworks, their reaction and feelings are articulated in detail. What they are actually looking at – the art – less so. Is there a danger that if you describe the works too clearly they’ll fall short of the supposed response?

It’s purposely suggestive. I don’t want people to see it. Once people see it it’s concrete and it’s done. It’s never going to be unseen. It’s like what I said about Rachel Whiteread’s doll houses – you don’t know why you’re reacting. Why should you? What is it about them? I could describe them all day but you’re not going to get the emotion until you see them yourself.

So I thought, hint at the art. The thing that is really important about good art is how you feel. To me it is always a surprise. So that was what I was concerned with. I suggest enough to show I’m not playing around. I’m serious that they’ve come together and made this art, something that is bigger than both of them, which, frankly, is also what a relationship is.

Is there anything that visual art can do that literature can’t?

Nope – literature can do anything. Nope. Nope. Nope. Any art can do anything. I tend to respond more to literature and music, but that doesn’t mean that I’m right or wrong. It’s just what I’m responding to. Literature can do the same thing. It’s just how it does it and what affects you the most. It’s a personal thing.

You seem to love writing dialogue, but what is the heavy lifting when it comes to writing a novel?

One of the hardest things to do is the passage of time. Just those simplest links I have to really work at. Things like, ‘Later that day…’ I know I’m not alone in this. Otherwise I end up writing a book that happens in this long, continuous, unbroken thing. I have done that. So I work on shifts in time. I worked on that in The Crane Wife. I faced it head on, but it’s not something I naturally do. But that’s a quirk. Every writer will have something that they’re less comfortable with.

As someone who has had great success writing for the young adult market and whose latest novel is pitched for a slightly older reader, what’s the difference between a YA novel and a novel for adults?

There’s obviously no rule, and there’s a million exceptions to every definition. I’ve always thought it is how you experience the novel. But if you are reading it and feeling your teenage self right then, then it’s probably a YA novel. And if you experience it as an adult, even if it has a teenage protagonist, it is an adult novel. And there’s probably exceptions to that. Basically, you know it when you see it.

I feel The Crane Wife tries to impress upon us that the extraordinary is all around. Things that we dismiss as everyday are actually full of wonder. Am I imagining that or is this something you were trying to communicate?

That’s totally what I’m after. That we exist is ludicrous. And yet we do. The capability that I have to move the muscles in my mouth to speak these words that we both agree have a meaning, is extraordinary. It’s impossible that it happens. Impossible.

In The Crane Wife everything is explainable if you want it to be except one thing, because there are inexplicable things in life. You are never going to be able to explain and figure out everything. So we make meanings for these gaps that aren’t necessarily satisfactory because we have to. That is how we live our lives, by telling stories about ourselves.

So do you think that explanations can diminish things, make them concrete and small?

We have to have stories or it will kill us. My long standing theory is that sentience is an evolutionary accident. It has huge evolutionary advantages to be aware of yourself, but it came with this enormous baggage that we weren’t ready for. We weren’t ready for death, so we invented religion. We weren’t ready for life, so we invented comedy. We just weren’t ready for it. But we are resilient, and we’ve evolved and found a way.

It’s impossible to think about death – to know you are going to die – so we’ve had to find a way to live with the impossible. And that’s where stories come from – they let you deal with the impossible, they let you live without having to spend every moment in waking terror.

What extraordinary things have happened to you today?

Sometimes it’s just waking up. Choking down burnt French Toast. Meeting a really shy kid who couldn’t say anything. Just that a story that I wrote for myself, that I wrote in front of a computer over a long long time, has somehow made it into this kid’s life and he’s really enjoyed it so much he wants to meet me, but he’s so shy he can barely say anything beyond his name. That’s extraordinary. Human connection – even a little one like that – is amazing.

The Crane Wife is out now in hardback and ebook editions.

_________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every week. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.