Queer Superhero History: Starman and DC’s First Gay Kiss

In recent years, mainstream comics publishers like DC and Marvel have made great strides in increasing the LGBTQ+ rep in their universes, though they still have a long way to go. But getting here was a slow and gradual process, with many notable landmarks — and some admitted missteps — along the way. In Queer Superhero History, we’ll look at queer characters in mainstream superhero comics, in (roughly) chronological order, to see how the landscape of LGBTQ+ rep in the genre has changed over time. Today: Starman (Mikaal Tomas)!

Throughout the ’90s, DC slowly but surely added more queer superheroes to their roster: Pied Piper, Tasmanian Devil, Icemaiden, Hero, Comet. Like his predecessors, Mikaal is relatively obscure — Starman isn’t exactly a household name, after all, and Mikaal is only the third or fourth best-known Starman anyway. But he is notable for sharing the first on-panel gay kiss in the mainstream DC universe — and he also illustrates how queer representation can fail when looking past historic “firsts.”

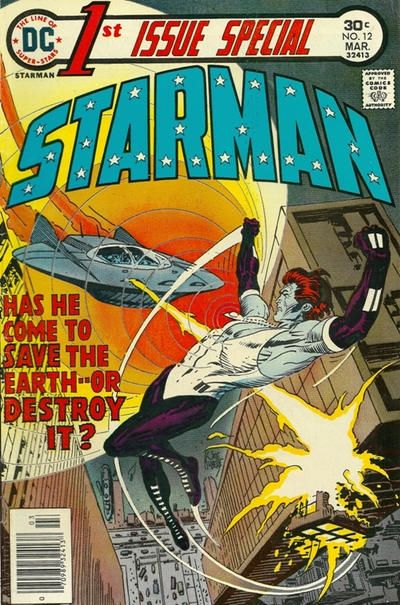

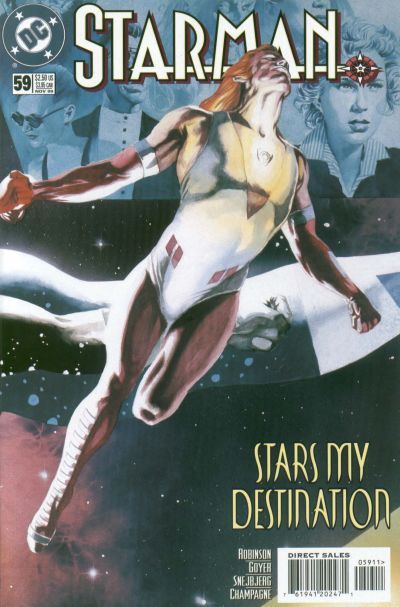

Mikaal debuted in 1st Issue Special #12 (March 1976) in a story by Gerry Conway and Mike Vosburg. He is an alien who is sent to Earth as the vanguard of an invasion but turns against his own people in defense of Earth instead. It’s a one-and-done story, and Mikaal would have remained an obscure bit of trivia (well, more obscure than he already is) if it hadn’t been for James Robinson and 1994’s Starman.

The phenomenal 1994 Starman series ran for 80 issues, and over the course of those issues, Robinson not only introduced a new Starman — Jack Knight, the son of the original 1940s Starman — but folded in every character who had ever been Starman. Mikaal shows up when Jack finds him imprisoned as part of a rural sideshow. Jack frees Mikaal, but due to the trauma of his imprisonment, Mikaal has forgotten how to speak English; even when he regains the language, he has amnesia, and his powers only manifest in rare moments of extreme stress.

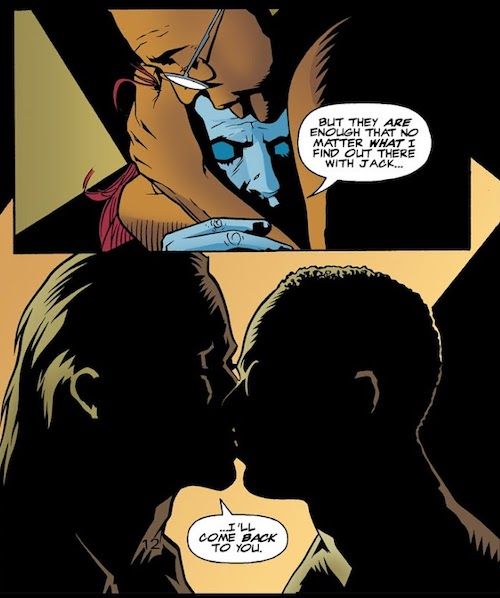

Mikaal settles down to civilian life in Jack’s hometown of Opal City, and in Starman #45 (August 1998), it’s revealed that he’s in a serious relationship with a human man named Tony. This is the issue that contains that historic kiss. DC had published queer kisses in their Vertigo imprint but never in their mainstream superhero universe, making this a major landmark in queer comics representation. (Mikaal and Tony are also shown relaxing in bed together, which was maybe even more daring.)

Like other ’90s heroes, Mikaal balks at labels. As his memory and powers come back, he remembers a female love interest from his origin story, which confuses Jack, who thought Mikaal was gay. “I’m an alien, Jack,” Mikaal says. “My actions are natural to my race, and shouldn’t…can’t be judged by human standards. No more than dolphins.” Queer characters rejecting labels is a stereotype even among the small pool of characters we’re already discussed in this series, and I don’t love equating queerness to an unknowable other or, um, literal animals, but considering that this comic is 25 years old and, I believe, well-intentioned, I’m willing to let it slide.

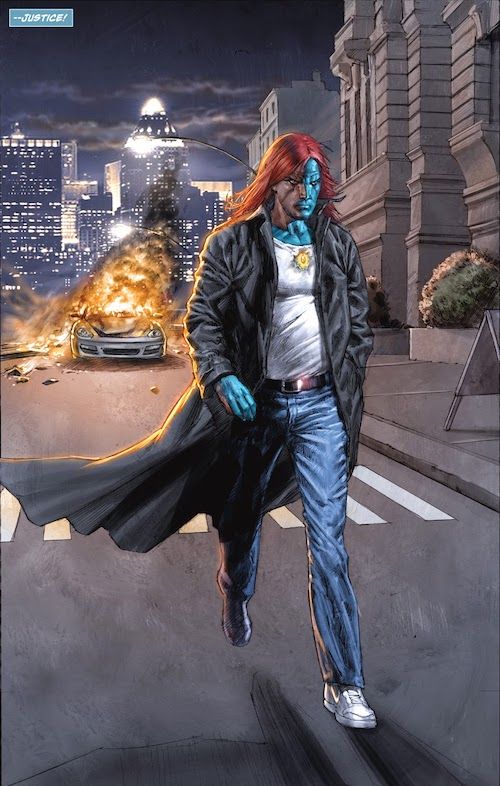

After Starman was canceled in 2001, Mikaal faded into obscurity. He rejoined the fray for 2009’s Justice League: Cry for Justice, also by Robinson. But while Starman is a masterpiece, Cry for Justice is pretty much the nadir of the late 2000s trend towards extreme violence, pessimism, and grimacing heroes behaving appallingly.

It was also not an era that was kind to marginalized characters. You might remember our friend Tasmanian Devil being skinned and turned into a rug in this comic. And so Mikaal’s storyline begins with Tony being killed in an explosion caused by supervillain activity, and Mikaal embarking on a vague, grimacing quest for…uh, justice, I guess.

After Cry for Justice, Mikaal and his friend Congorilla (a golden gorilla with the mind of a human, obviously) teamed up for — what else — the Starman/Congorilla one-shot. Mikaal is spiraling, deeply grieving his partner of 12 years, when the two meet Tasmanian Devil (miraculously healed from his ruggification). Congorilla does his best to matchmake, and I’ve found a number of online sources that claim Mikaal and Hugh started dating at this point, but no actual comics depicting them together.

Mikaal then briefly joined the JLA, but his entire history was effectively erased by the New 52 reboot in 2011 — and theoretically effectively restored by the Infinite Frontier reboot in 2021. However, he’s currently appearing in Danger Street, which ignores all of his history beyond his first appearance and all of his characterization…basically ever. Instead, he’s an anxious, insecure wannabe hero desperate to join the Justice League who, uh, accidentally murders a child. His sexuality is never mentioned.

In the late ’90s, Mikaal was a groundbreaking character. Queer heroes were even more thin on the ground than they are now, and being part of DC’s first on-the-page gay kiss was a majorly significant moment. Yes, Mikaal comparing his sexuality to dolphins (seriously, what) is a bit eye-rolly now. But the matter-of-fact way Mikaal’s sexuality is addressed, the total acceptance of all the other characters, and the way Mikaal’s relationship with Tony is positioned as just as normal and sincere as Jack’s with his girlfriend are all really progressive and lovely to see.

But portraying a marginalized character respectfully isn’t just about ticking off boxes — First Gay Kiss in a Mainstream DC Comic, check! Take Cry for Justice. No one gets off easy in that book, which remains infamous 14 years later for, among other things, ending with the murder of a 5-year-old girl. Now, I’m not saying that female characters, characters of color, queer characters, etc., should be off-limits (5-year-olds, maybe). At the end of the day, these are stories about violence and its consequences.

But when characters who aren’t straight white men make up such a small fraction of superhero universes, killing them has an outsized impact. Between Tony and Hugh, fully 66% of the queer characters who appear in Cry for Justice are murdered. Tony’s death alone means that half of the Black men in this book appear only as a corpse.

There are, of course, dozens of straight, white characters in Cry for Justice.

In a text piece in the back of Cry for Justice #4, Robinson wrote: “Ironically Tony will have more of a life after his death than he ever did as a comic book character prior to now. His memory will help to shape, hone, and refine Mik as we see Mik’s life and greater involvement in the DCU after this series ends.”

This isn’t the reassurance Robinson seems to think it is. Marginalized characters are frequently sacrificed to the story gods to further the narrative. A gay Black man in a 12-year relationship was a novelty. A gay Black man dying, or his surviving partner being left to grieve that loss, was not. And to add insult to injury, we didn’t ever really see that greater involvement in the DCU for Mikaal that was promised, thanks to the New 52.

Danger Street treats Mikaal in a similarly cavalier way. It’s an ensemble book about various characters who appeared in 1st Issue Special, and a major part of the book is mixing and matching these obscure heroes and villains. But why is a character who shared a landmark kiss still so obscure in the first place? Danger Street only cares about Mikaal’s origin issue in 1976, but 1976 isn’t the most important year for Mikaal. 1998 is.

Extraño, DC’s first gay hero, was dismissed as an embarrassment for decades before being updated with care and respect for a modern audience (and married to DC’s second gay hero, Tasmanian Devil, putting an end to whatever relationship Hugh and Mikaal may or may not have had). I’d love to see DC treat Mikaal with similar respect for his historical importance — and to remember that characters who might seem like disposable third-stringers to more privileged readers might be rare and shining beacons of representation to others.