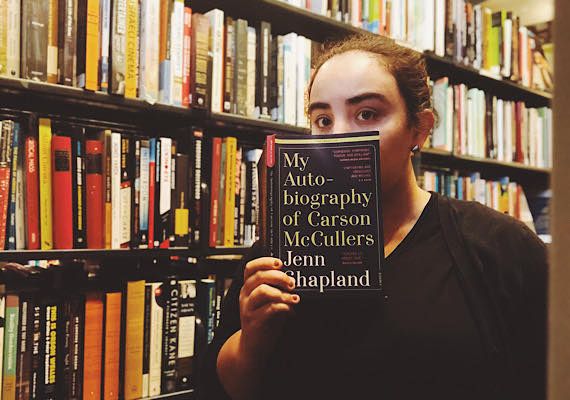

Seeing My Queer, Ill Self in Jenn Shapland’s New Memoir

This past September, I got sick twice in a row. It sucked, but what can you do? I was ready to move on with my life. But something else wasn’t letting me go that easily. At first I just felt out of it. The exhaustion in particular was new, and strange. I’m an insomniac and often tired, but now I was weary, and more than that, I had to fight to stay awake as early as 7:00 PM. Something wasn’t right, but when I went to see a doctor, they did a few tests and then just told me to come back if something got worse. All I could do was push forward, which after all was nothing new to an insomniac—as Jenn Shapland writes truly in her new memoir, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers: “exhaustion is not a quality that the world takes very seriously.”

But then my symptoms got worse, and they got worse fast. I started to have trouble focusing on my screen. My heart wouldn’t stop pounding. When I tried to sleep, my heart would rocket, and my breaths would feel short and ineffective. I felt like I was going to faint after any flight of stairs. My symptoms were consistent, and terrifying.

In her memoir, Jenn Shapland links her chronic illness to her queerness, to fear, and to realness. It took months of testing for Shapland to be diagnosed with POTS, a chronic illness that causes extreme fatigue and migraines, among other symptoms. Carson McCullers had several strokes before doctors realized what they were and traced them back to a heart condition.

“My own chronic illness,” Shapland writes, “connects to fear, the feeling of not being real that accompanies queer womanhood. I don’t always remember or believe my illness is real, because there is no reflection of it outside myself, my own feelings.” She writes that on her worst days, no one can see that she is any different—but it’s also difficult to bring it up. “When I am a body in pain,” she writes, “I have only self to turn to. Even well-meaning others can’t see or know or feel the facticity of all my skin aching at a light draft.”

I experienced a deep, aching loneliness as I tried to figure out what was wrong with my body. One doctor put me on allergy meds. Another told me that it could most likely be fixed by diet and exercise, patting his own stomach as he said so. Another tested me for the flu, mono, and strep, and when all came back negative, she had no more suggestions. I was losing control of my body and no one seemed to know why. I would take a day off work, be in the next day, and be out the one after that, and I started to get anxious that people at work would think I wasn’t actually sick. I started to wonder if I was, and would chastise myself, hydrate, and go to sleep early with plans to go suck it up and go to work the next day—and then I’d wake up in the middle of the night with my heart pounding, a sharp pain stabbing under my left breast, feeling dizzy and sick, and I’d call another doctor for another appointment, I’d schedule another day off.

The final straw was when a doctor x-rayed my lungs, found nothing, and then told me in no uncertain terms that it was my anxiety, or my anxiety medications, that were making me feel this way. When I tried to tell him they didn’t remotely resemble my anxiety, he brushed me off and insisted. So I called my psychiatrist, explained what had been happening, and within a week, I was sitting in a cardiologist’s office on her referral. And the cardiologist was a reasonable human being, thank god. He read all my notes, listened to every symptom and worry I had, and then said, “I know what this is. This is textbook.” My eyes filled up with tears, and he hurried to tell me that it wasn’t serious. I shook my head. “No, I’m relieved,” I said, and it was the truth.

Twenty minutes earlier, I had told my boyfriend in the waiting room that I no longer cared what it was, as long as they found out. Well, hopefully, not something serious, he amended, and I shook my head. “No, I don’t care,” I said, feeling that stabbing in my chest. “I just want him to believe me. I just want to know.” I paused to catch my breath. “I just want proof that it’s real.”

It was real. It was pericarditis, which is a swelling of the sac around the heart that I should recover from completely. I’m on anti inflammatories now, and have been feeling like myself again for quite some time. But for months, I was suffering from an invisible illness that no one could see, and my deepest fear was that no one would ever see it. And even when I knew the diagnosis, I still struggled with this—I would over-exert myself and then chastise myself for feeling like I’d been run over by a truck, or for cancelling plans due to fatigue, and only later realize that my illness was to blame, reminding myself that it was ok and real, legitimate, that I needed rest and recovery.

And so, when I read Shapland’s line, “the feeling of not being real that accompanies queer womanhood,” it struck me deeply. Because it was true. That fear of not being real, as hard as it is, is a part of my identity as a queer, mentally ill, woman, and it always has been.

And so, when I read Shapland’s line, “the feeling of not being real that accompanies queer womanhood,” it struck me deeply. Because it was true. That fear of not being real, as hard as it is, is a part of my identity as a queer, mentally ill, woman, and it always has been.

For an example, cut to me, age 24. I knew that I had a history of high-functioning clinical depression; I was already seeing a therapist for generalized anxiety disorder weekly; and I knew about all the stigmas. But even as I began to feel more irritable, trying and failing to get out of bed, feeling low motivation, a deep emptiness spreading across my chest, even as I suspected depression, it took me almost a year to mention it to my therapist, because I was worried she wouldn’t believe it was real. And I was worried that, perhaps, it wasn’t.

Or cut to me, age 20. I’ve been pansexual all my life, but like Shapland, it was only after years of fake crushes on distant men and mismatched socks as fashion statements that I was able to make my queerness public, to insist that even though I had no proof, I was allowed to take on the label of pansexual. Not because I have evidence that it’s “real.” But because I know that I am.

It’s no easy thing to impose yourself on a world that renders you invisible. In a passage that left me breathless, Shapland wrote, “If Carson was not a lesbian, if none of these women were lesbians, according to history, if indeed there hardly is a lesbian history, do I exist?” When there is nothing visible, no hard evidence or proof, people who are suffering can only gesture to what we know within ourselves, and hope that we can someday be seen, recognized, as true.

“I go on long walks for my weak heart,” writes Shapland, “but I am still a queer, sick, writing person—woman—living in the world.” Shapland’s quest for visibility and her struggle with identity resonated deeply with my own hopes and fears, and I am grateful to her and her book.