10 Things You Need to Know about the Sana’a Pentateuch

Yemen is a country that somehow feels further away than most. Located on the south-west part of the Arabian Peninsula, news about Yemen only seem to reach us when there is a tragedy.

But Yemen is so much more than the occasional news story from a far away land. Yemen is a country with an old civilization capable of wonderful art.

Book art.

One of the most famous books from Yemen is the so-called Sana’a Pentateuch. Sana’a is the capital city of Yemen and a Pentateuch consists of the first five books of the Torah, also known as the Five Books of Moses. In Christianity these books are known under the names of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

The roots of the Jewish community of Yemen are clouded in history. According to one tradition, Jews arrived in what is now Yemen after the Queen of Sheba returned from her visit to King Solomon. Another tradition says they arrived after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E. Archaeologically, the first traces of a Jewish community have been dated to around 110 B.C.E.

Today, very little is left of the Jewish community of Yemen. Because of persecution and poverty, most of them have moved, either to the United States, the United Kingdom, or Israel. A group of fifty people remain in the country.

Even though this community with ancient roots no longer exists, some of the beautiful books that they produced have survived to our day, including the Sana’a Pentateuch.

Here are ten things you should know about the Sana’a Pentateuch.

1) The Sana’a Pentateuch was made in Sana’a, Yemen, in 1469. The Pentateuch is a codex, in other words what we call a book, unlike most other Judaic holy texts that are written on scrolls. The Pentateuch consists of 158 folios. The folios are 40 cm tall and 28 cm wide, or 15.74 inches by 11 inches.

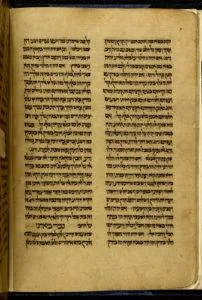

Dark ink on orange-tinged paper, typical for Yemenite Hebrew manuscripts from the Middle Ages (Sana’a Pentateuch, British Library, Oriental 2348 f. 15v).

2) The Sana’a Pentateuch is written on paper. The paper used has an orange tinge, which is typical for Yemenite Hebrew manuscripts from the Middle Ages.

3) The Sana’a Pentateuch is written in Hebrew, using the type of square script that developed in Yemen. The ink is very dark, this too typical for Yemenite Hebrew manuscripts from the Middle Ages.

4) The Sana’a Pentateuch was made by a scribe named Benaiah ben Saadia ben Zekhariah ben Marga (d. 1490). Even though Benaiah doesn’t identify himself in the manuscript, his style is so distinctive that the writing and the decorations of the Sana’a Pentateuch match other manuscripts where he has added his name.

5) The Sana’a Pentateuch was commissioned by a man named Abraham ben Yosef al-Israili. Abraham is a known patron of several surviving manuscripts, and he hired Benaiah to work on several of them.

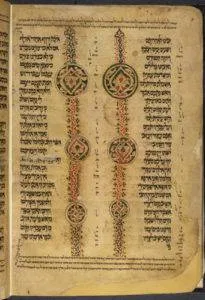

Parallel lines displaying a blend of Judaic and Islamic influences (Sana’a Pentateuch, British Library, Oriental 2348 f. 152v).

6) The Sana’a Pentateuch is famous for its beautiful decorations using micrography. Micrography is a Jewish art form where text in Hebrew or Aramaic is written as outlines of images. Micrography developed in Egypt and Palestine in the seventh and eighth centuries C.E. as a way of circumventing the rule not to include images in the holy texts of Judaism.

7) Yemenite micrography reached its peak in the fifteenth century. It tends to favor simple geometric parallel lines and recurring motifs.

8) The Sana’a Pentateuch is famous for its recurring patterns where Jewish elements blend with Islamic influences, probably inspired by trends in contemporary Yemenite crafts.

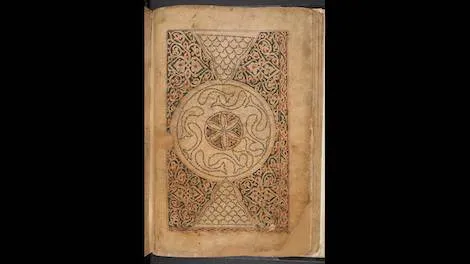

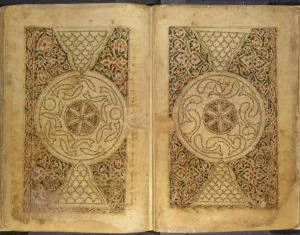

9) The Sana’a Pentateuch is also famous for its lavish carpet pages and for its intricate micrographical representations of fish swimming in the sea.

Carpet page with micrography. The outlines of the fish and scales consist of lines taken from the Book of Psalms (Sana’a Pentateuch, British Library, Oriental 2348 ff. 38v–39).

10) It can be found at the British Library. The British Library bought the manuscript on May 28, 1881 from Mr. Nic Mavrocordato.

If you would like to flip through the pages of the Sana’a Pentateuch, the manuscript has been digitized in its entirety and can be viewed here.

If you would like to know more about beautiful Jewish manuscripts from the Middle ages, click here for ten things you need to know about the Golden Haggadah.