Picture Books To Teach Children About Residential Schools

The history of Indian Residential Schools is foundational to understanding Canada as it is today. In British Columbia, learning about residential schools is part of the curriculum from elementary school onwards, but that is not the same across Canada or the U.S., who have their own history of American Indian Boarding Schools — or even Australia, who have the history of Stolen Generations.

There’s also a difference between what’s technically in the curriculum and what is actually being taught — and how. Whether you are a parent or a teacher, teaching children in your care about this history is essential, because you can’t assume someone else already has or will in the future sufficiently. The repercussions of residential schools are being deeply felt by generations today, and education is one small piece of how we can grapple with this.

In this post, I will highlight a few picture books that can start conversations about residential schools with kids. I also have a list for adults: Books About Indian Residential School In Canada: Nonfiction and Fiction. I want to preface this by saying that I am not an expert. I am not Indigenous. The best way to make sure you are being respectful and getting accurate information is to make connections with your local Indigenous nations. For example, the Native Friendship Centre in my city has a library that is open to anyone (for $1 a year membership), and they are happy to give recommendations, whether you have no idea where to start or want to dive more deeply into a specific research area.

I also recommend checking out the First Nations Education Steering Committee, especially if you’re in British Columbia. They have a page for authentic First Peoples resources, and they also have free in-depth lesson plans for teaching English First Peoples. There’s also Strong Nations, an Indigenous-owned online bookstore with a huge catalogue to help you find more titles.

Usually, we link titles using affiliate links, but I invite you to find an Indigenous-owned bookstore to order these from. I’m a personal fan of Iron Dog Books, but here is a list of more across the U.S. and Canada.

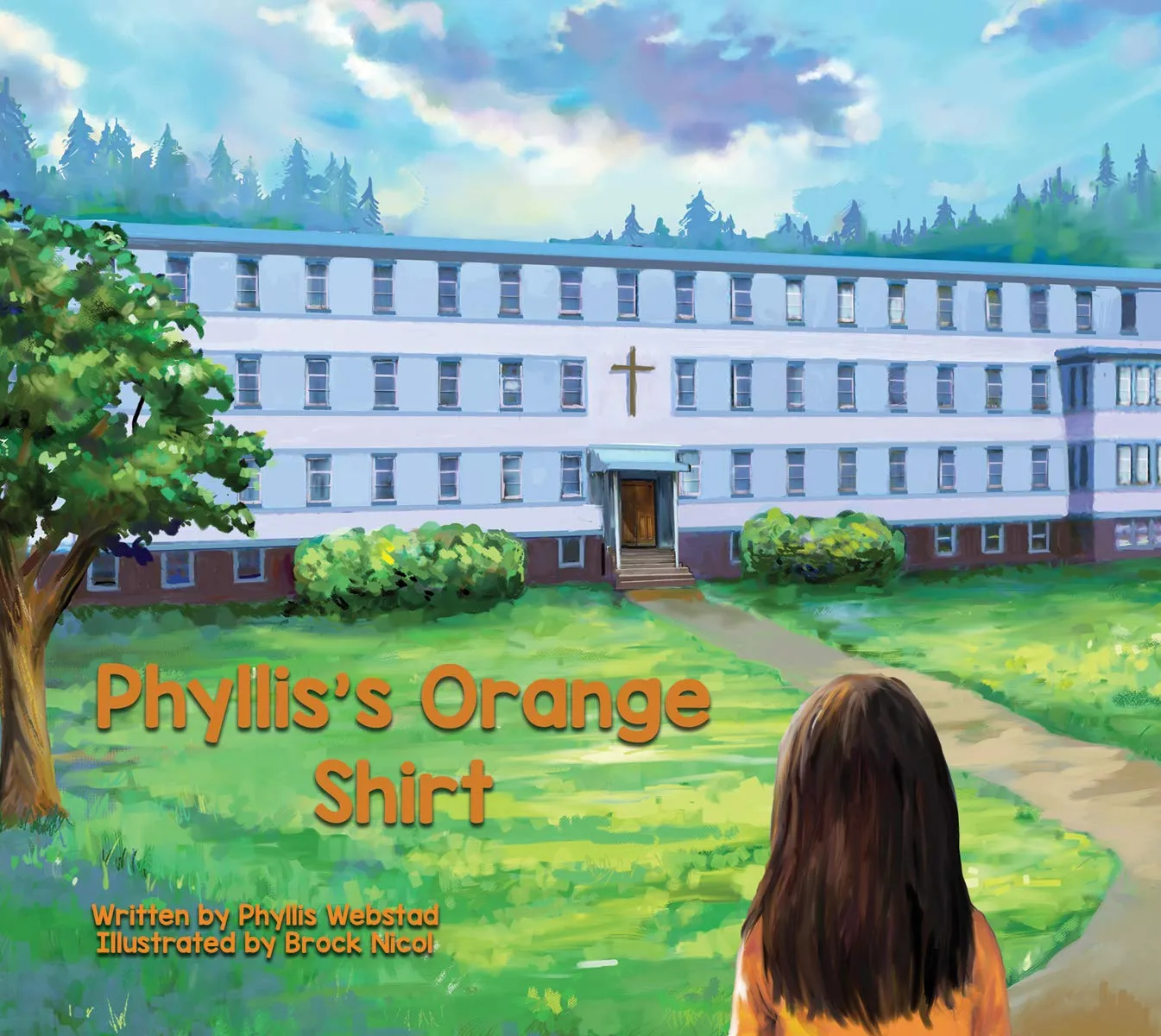

Phyllis’s Orange Shirt by Phyllis Webstad and Brock Nicol (Grades Pre-K to 1)

Orange Shirt Day, September 30, is a day of remembrance for those who went through residential schools. The significance of the orange shirt comes from Phyllis Webstad’s story of wearing a shiny new orange shirt her grandmother gave her for her first day of school, only to be stripped of it and never see it again. She explains, “The color orange has always reminded me of that and how my feelings didn’t matter, how no one cared and how I felt like I was worth nothing.” On Orange Shirt Day, wearing an orange shirt helps support her message that Every Child Matters.

This is an adaptation of her story suitable for young readers, with a sentence per page and age-appropriate content. She also has a middle grade version of this story called The Orange Shirt Day Story.

Phyllis Webstad is Northern Secwpemc (Shuswap) from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation (Canoe Creek Indian Band).

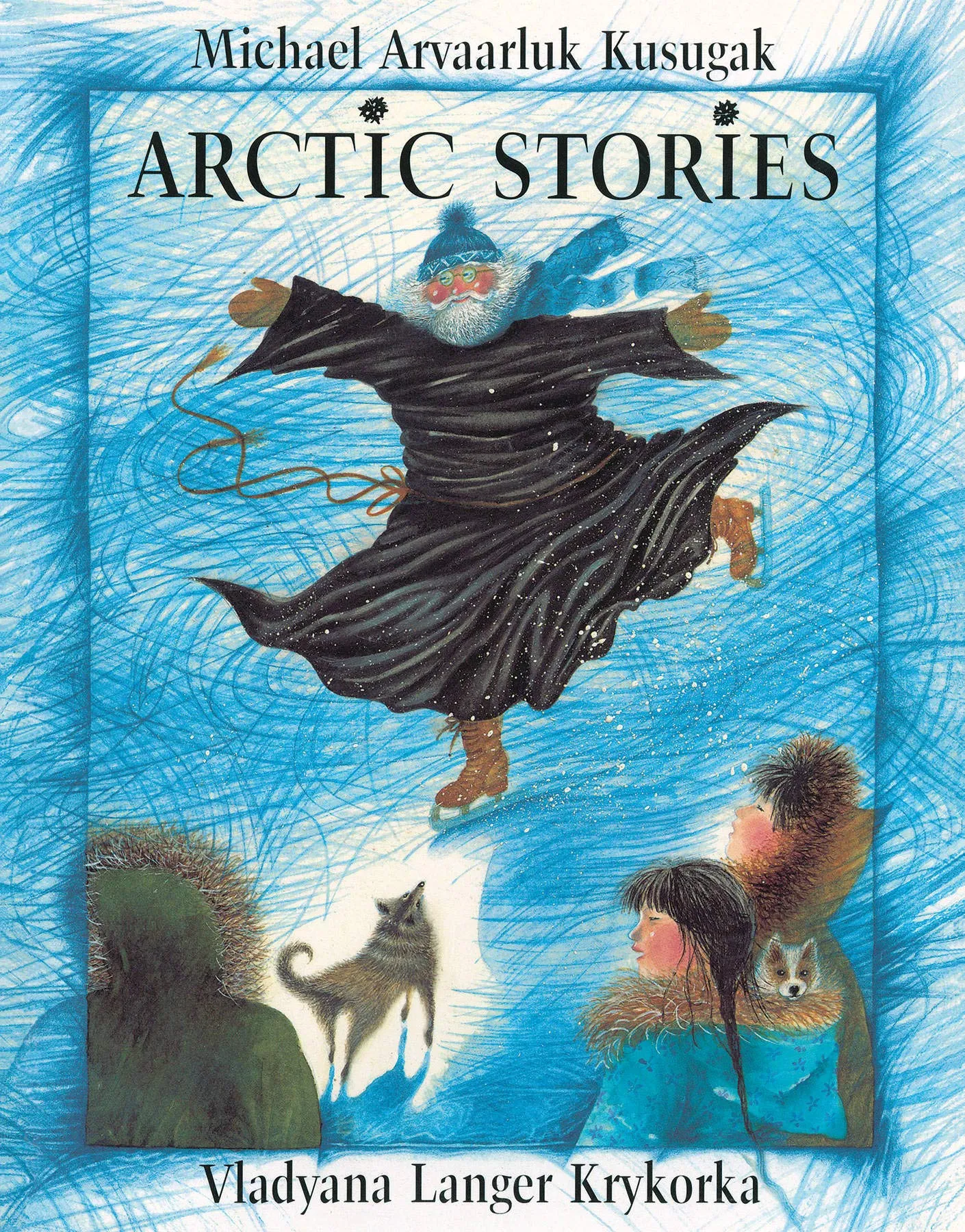

Arctic Stories by Michael Kusugak and Vladyana Krykorka (Grades Pre-K to 3)

If you want to ease into conversations about residential schools, this is a good choice to start. It’s a collection of stories based on the author’s childhood experiences, starring a 10-year-old Inuit girl, including her experiences being taken to an all-English boarding school. This doesn’t give a lot of details, but even very young children can discuss what it would be like to go to school away from your family and not being able to speak your own language.

Michael Kusugak is Inuit.

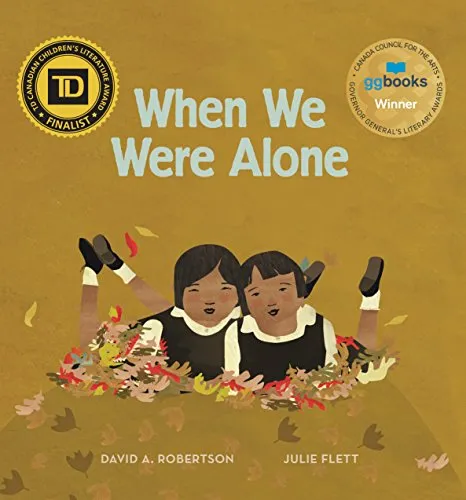

When We Were Alone by David A. Robertson and Julie Flett (Grades K-3)

A grandmother and granddaughter tend their garden together as the grandmother explains her time in residential school, “when we were alone.” This blends together stories of what they went through at these schools with examples of resistance and the resourceful ways that children were able to hold on to their culture — which she is now passing on to her grandchild.

David A. Robertson is Swampy Cree and Julie Flett is Cree-Métis.

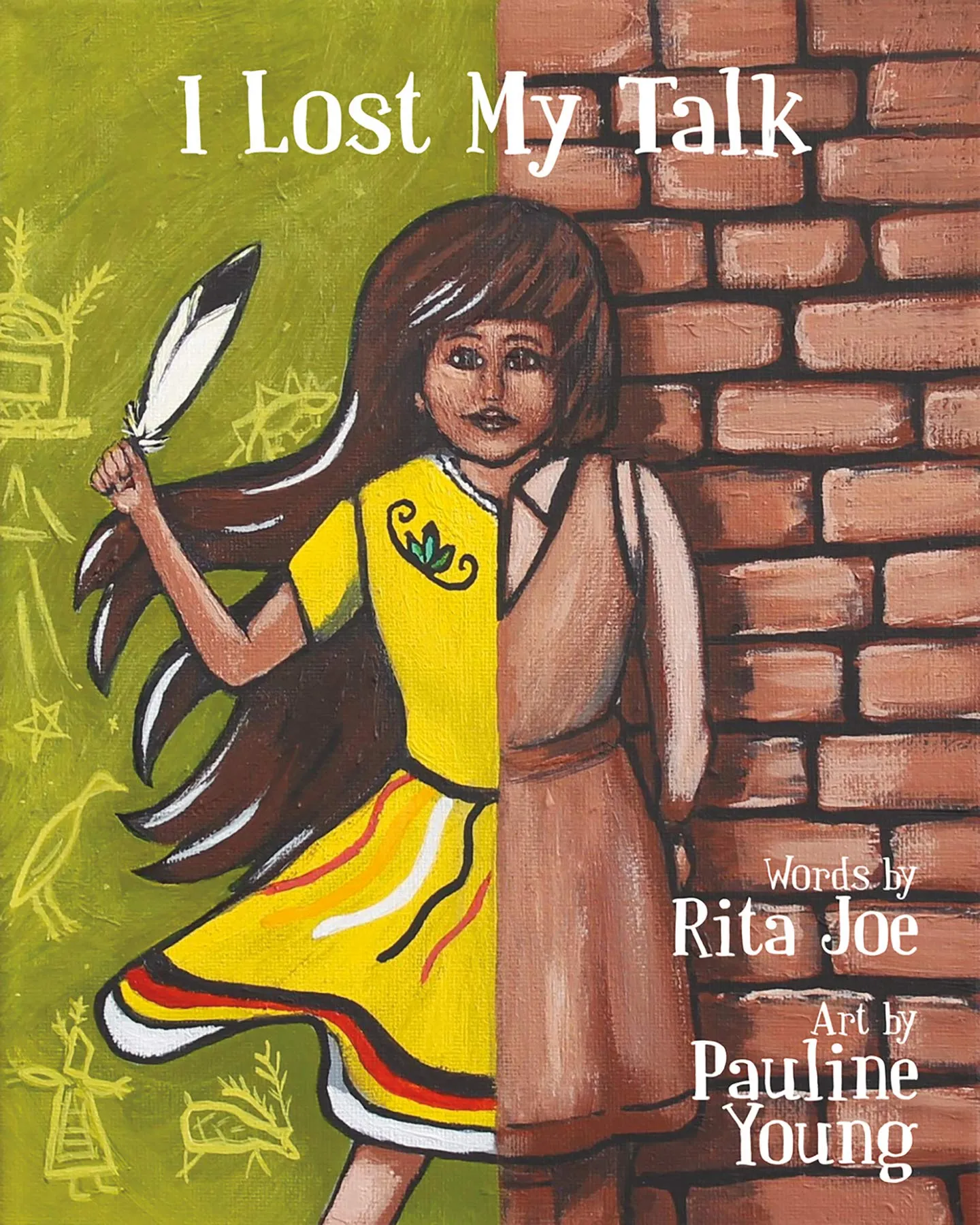

I Lost My Talk by Rita Joe and Pauline Young (Grades K to 3)

“I Lost My Talk” was originally a poem and has been taught by many schools in a range of grades. Now available in a picture book format, it’s the story of Rita Joe’s experience at residential school in Nova Scotia — especially of being denied her language. There is a note at the end of the book with more information about residential schools.

Published simultaneously was I’m Finding My Talk by Mi’kmaw activist and spoken word artist Rebecca Thomas, also illustrated by Pauline Young. In this companion picture book, Thomas discusses rediscovering her community and culture as a second-generation residential school survivor.

Rita Joe and Pauline Young are Mi’kmaw.

Stolen Words by Melanie Florence and Gabrielle Grimard (Grades 1-4)

Another story told between grandparent and grandchild, this begins with a little girl asking her grandfather how to say something in Cree. He admits that his language was stolen from him when he was young. She is determined to help reclaim his words.

This title also has a teaching guide for grades 1–4.

Melanie Florence is of Cree and Scottish heritage.

Not My Girl by Christy Jordan-Fenton, Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, and Gabrielle Grimard (Grades 1-4)

This is a heart-wrenching story of a 10-year-old girl who comes back to her community after two years at residential school. She has lost much of her language and culture, and she is unrecognizable to her community. Her mother cries, “Not my girl” when she sees her. It follows Margaret relearning her culture and language, trying to reintegrate back into her community. This is a great story to start a conversation about the lasting effects of residential schools.

Margaret Pokiak-Fenton is Inuit. (Christy Jordan-Fenton is her daughter-in-law.)

Chester Nez and the Unbreakable Code: A Navajo Code Talker’s Story by Joseph Bruchac and Liz Amini-Holmes (Grades 1-5)

Chester Nez was a Navajo Code Talker during WWII, and this follows his journey through residential schools as a child, to his time in the army, to his difficulty in adjusting post-war. It describes the shock of moving between vibrant summers with his family and the cold treatment he receives at school, but those summers help him to survive the rest of the year. The subject of this book also wrote an autobiography, if you want the full version of this story: Code Talker: The First and Only Memoir by One of the Original Navajo Code Talkers of WWII.

Joseph Bruchac is a Nulhegan Abenaki citizen.

Shi-shi-etko by Nicola I. Campbell and Kim LaFave (Grades 2-3)

This is a beautiful picture book about a girl preparing to be taken away to residential school. While she counts down the four days she has left, she tries to make memories of everything she will miss, from the landscape around her to her family. Her mother, father, and grandmother give her advice on teachings to remember during her time there.

There is an accompanying short video available on YouTube as well.

Nicola I. Campbell is Interior Salish/Métis.

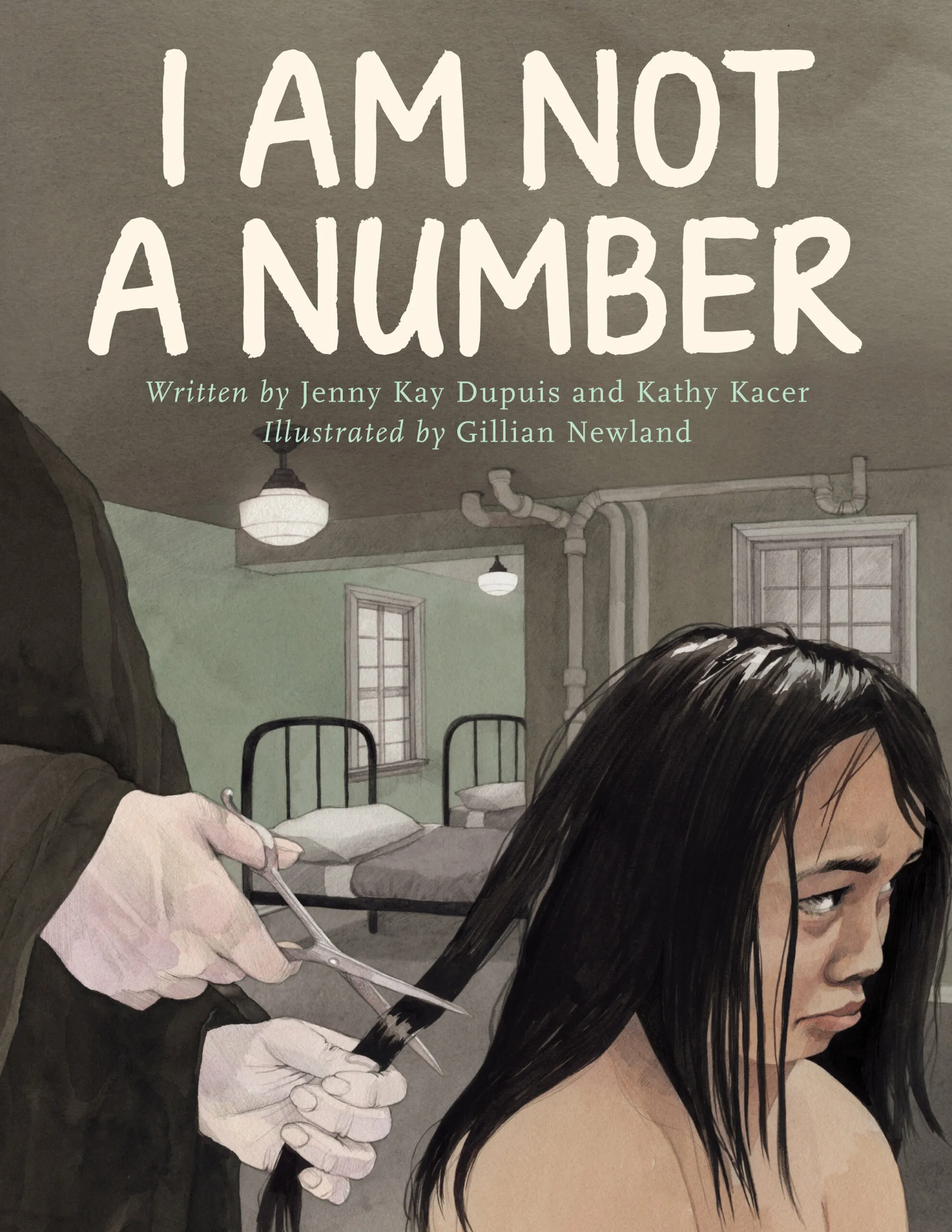

I Am Not A Number by Jenny Kay Dupuis, Kay Kacer, and Gillian Newland (Grades 3-6)

Based on Dupuis’s grandmother’s experiences at residential school, this follows Irene, who is 8 years old when she is taken from her family to go to residential school. There, she is referred to only as a number. When she returns home for the summer holidays, her parents decide they’ll never send their children’s there again — but that means they’ll have to find a way to hide them. This includes an author’s note in the back with more information of the facts the story is based off.

Jenny Kay Dupuis is of Anishinaabe/Ojibway ancestry and a member of Nipissing First Nation.

When I Was Eight by Christy Jordan-Fenton, Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, and Gabrielle Grimard (Grades 4-7)

This is an adaptation of Fatty Legs for younger readers. It discusses Margaret Pokiak-Fenton’s experience at residential school, especially her excitement to learn to read, which she maintains even when faced with a nun who cuts off her hair, makes her perform menial tasks, and bullies her. The subject matter is less dark than the original, made age-appropriate for this grade range.

Margaret Pokiak-Fenton is Inuit. (Christy Jordan-Fenton is her daughter-in-law.)

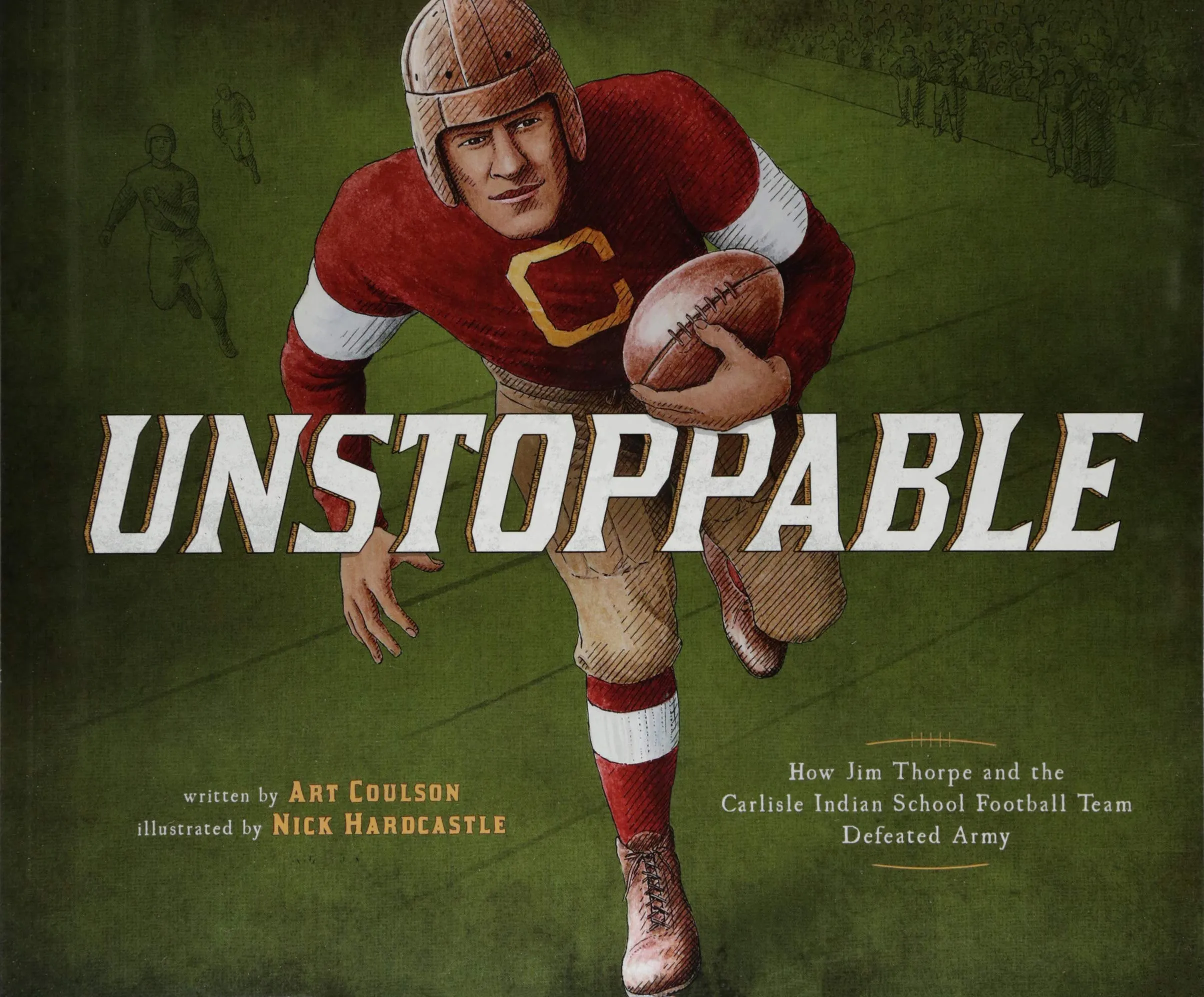

Unstoppable: How Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indian School Football Team Defeated Army by Art Coulson and Nick Hardcastle (Grades 4-7)

This is a good pick as a supplementary story, because it doesn’t focus on the residential school system itself. Instead, it’s about a historic football game in 1912 between Carlisle Indian Industrial School and West Points Cadets, one that was covered by journalists as a “rematch.” Four future generals were playing for Army, as well as a future president — but the smaller, ill-equipped team led by Jim Thorpe took the day. As Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese explores, sports were often a part of residential schools — and acknowledging that children may have taken refuge in that does not erase the trauma of their experiences overall.

Art Coulson is Cherokee.

If you want to read adult books about residential schools, here is a list of history books, memoirs, novels, and poetry that tackle Indian residential schools in Canada.

I invite you again to purchase these books from an Indigenous-owned bookstore if possible.

The impacts of residential schools are long-lasting. Donate to the Indian Residential School Survivors Society and Orange Shirt Day to help heal survivors and their families and educate others about Canada’s continuing legacy of genocide.