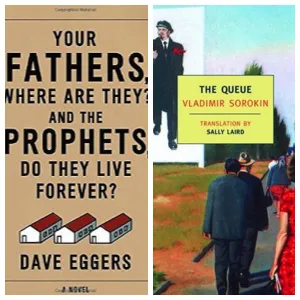

Read This Then That: New Dave Eggers and THE QUEUE

In Read This, Then That, we pair new books with classics that have similar themes, structures, and stories.

Let's be realistic. The first thing that will strike you about the new Dave Eggers novel is its title: Your Fathers, Where Are They? And the Prophets, Do They Live Forever? But the second thing is surely its structure. Though divided into fairly traditional chapters, the entire novel consists of dialogue, unpunctuated by narration, between the protagonist, Thomas, and various people he goes to seeking answers—answers to why the world is the way it is. Dialogue that is destined to be unfulfilling.

What's impressive about Your Fathers, though, is that Thomas's exchanges aren't unfulfilling, and Eggers's avant-garde structure isn't gimmicky. Of course, it's also not groundbreakingly avant-garde; Vladimir Sorokin's 1985 The Queue does it more and harder.

What's impressive about Your Fathers, though, is that Thomas's exchanges aren't unfulfilling, and Eggers's avant-garde structure isn't gimmicky. Of course, it's also not groundbreakingly avant-garde; Vladimir Sorokin's 1985 The Queue does it more and harder.

The Queue, like Your Fathers, fundamentally follows a single protagonist—though in Soviet Russia, novel protagonizes you. The main character spends days queuing for no one knows what. Suggestions are thrown out from time to time—boots? bread? jeans?—no one knows, but everyone waits in line. The dialogue is a wider conversation; people talk up and down the line, hold each other's places, take sexy side trips. Each night the queue disbands, to re-form in the same order the next day. And Sorokin's novel, deliberately structured with no exposition just as Eggers's is, does it all. Blank page after blank page for nighttime. And pages and pages of dialogue like this for morning:

—Luzhin!

—Yes!

—Podberezovikova!

—Yes!

—Znamenskaya!

—Titova!

—Yes!

—Popov!

—Yes!

Your Fathers is not Soviet bleakness and bread lines. Its continuous dialogue is not inane monotony spoken among near or total strangers; though misguided and confused, Thomas is a seeker. And while he's also a criminal—he admits in the first pages that he's kidnapped an astronaut to interrogate—his acts of increasing desperation don't add up to a massive, pathetic fall. Readers can decide for themselves how adequately Thomas's questions are answered, but there is a directionality in Your Fathers that is missing from The Queue. Sorokin's is an absurdist joke about waiting for God-knows-what, while Thomas follows a step-by-step plan designed to achieve a specific goal. Instead of random strangers thrown together in a line, Your Fathers comprises people who were somehow meaningful in Thomas's life, whether they realize it or not.

Your Fathers is not Soviet bleakness and bread lines. Its continuous dialogue is not inane monotony spoken among near or total strangers; though misguided and confused, Thomas is a seeker. And while he's also a criminal—he admits in the first pages that he's kidnapped an astronaut to interrogate—his acts of increasing desperation don't add up to a massive, pathetic fall. Readers can decide for themselves how adequately Thomas's questions are answered, but there is a directionality in Your Fathers that is missing from The Queue. Sorokin's is an absurdist joke about waiting for God-knows-what, while Thomas follows a step-by-step plan designed to achieve a specific goal. Instead of random strangers thrown together in a line, Your Fathers comprises people who were somehow meaningful in Thomas's life, whether they realize it or not.

But in a way, Thomas's problems harken back to the kinds of issues The Queue has at its heart. Thomas is up front about what he believes is his problem—and whom he believes is to blame. He tells a Vietnam veteran Congressman that "I'm pretty sure that I would have turned out better, and everyone I know would have turned out better, if we'd been part of some universal struggle, some cause greater than ourselves." Insulted by Thomas's naïveté, the double amputee tells him he thinks he wants to be part of a video game.

—I don't know. Actually, I think I do know. It's because nothing's happened to me. And I think that's a waste on your part. You should have found some kind of purpose for me.

—Who should have?

—The government. The state. Anyone, I don't know. Why didn't you tell me what to do? They told you what to do, and you went and fought and sacrified and then came back and had a mission...

Unsurprisingly, this is not the way to win over the Congressman, and a solid dose of The Queue might mar Thomas's faith in some ill-defined state plan just as the Vietnam War did to this veteran's. As it is, Thomas comes to fairly similar conclusions about the powers of men and their institutions, though with an undeniable hint of McSweeney's-tinged optimism that it's hard to say The Queue shares.

____________________

Can we interest you in a bookish t-shirt that not-so-subtly displays your love of reading? Can be yours for less than $20, shipping included. Get it here.