“I Just Feel”: In Praise of Simplicity in Fiction

When I tell people that “Feel” is my favorite song from Kendrick Lamar’s newest album, Damn., they seem confused. The song, on an album teeming with vociferous, anthemic bangers, is fairly unassuming, unfurling with a minimalist pitter-patter beat, Kendrick beginning each line with “Feel like” as he lists the things that make him anxious. The sentiments he expresses are, as my Composition and first-year Literature students like to say, “relatable”—especially in the Trump era.

I feel like I’m losin’ my focus I feel like I’m losin’ my patience I feel like my thoughts in the basement Feel like, I feel like you’re miseducated Feel like I don’t wanna be bothered I feel like you may be the problem I feel like it ain’t no tomorrow

Kendrick Lamar has become famous for his verbosely intelligent, complex raps—he can fill bars better than free alcohol—but it’s “Feel,” one of his most lyrically simplistic songs that hits me hardest. And the reason this song resonates is precisely because of its simplicity.

I find that I respond to this kind of simplicity in fiction as well. As an English major and later as an MFA candidate, I was often discouraged from using the verb “to feel,” that doing so was a sin against writing. Feelings, because of their apparent complexity, should be “unpacked”; it is lazy to describe how a character is feeling by using the “verb” feel. A beautiful sentence can never begin with “I feel.”

As a neurotic, introverted woman, I spend a ridiculous amount of time trying to sort out how I feel about everything. How do I really feel about my job(s)? How do I really feel about my sex life? How do I really feel about Rachel Maddow’s obsession with Russia? Consequently, I like to write about how people are feeling, and I also like to read about how people are feeling. Most of the time I read to have my own feelings reflected back to me in ways that are easy to understand. To this end, I feel like a well-placed sentence that begins with “I felt” or “She felt” is infinitely more effective—more stirring, more devastating—than trying to verbosely describe the feeling itself.

Students of fiction are often taught to avoid the verb “to feel” in writing, and yet we all revere—whether we like to admit it or not—Hemingway, the Patron Saint of Simple Feelings. Even though the quintessential Masculine Writer uses the verb “to feel” often, one way to read the discouragement of “feeling” in fiction is as a repudiation of something associated with femininity.

In much the same way I learned to “unpack” feelings in writing, I also had to learn to embrace the verb “to feel,” to utilize it to my advantage. The writer I learned this from was Akhil Sharma, whose books and stories are littered with “feels.” One sentence in “You Are Happy?”, Sharma’s most recent New Yorker story, goes: “Lakshman felt strange being alone at home with his mother, sitting at the kitchen table, doing his homework, while his mother drank upstairs.” In a writing workshop, “felt strange” would be derided, but by putting these two vagaries next to each other, it invites the reader to sort out what makes the feeling strange. It makes the text more interactive.

In much the same way I learned to “unpack” feelings in writing, I also had to learn to embrace the verb “to feel,” to utilize it to my advantage. The writer I learned this from was Akhil Sharma, whose books and stories are littered with “feels.” One sentence in “You Are Happy?”, Sharma’s most recent New Yorker story, goes: “Lakshman felt strange being alone at home with his mother, sitting at the kitchen table, doing his homework, while his mother drank upstairs.” In a writing workshop, “felt strange” would be derided, but by putting these two vagaries next to each other, it invites the reader to sort out what makes the feeling strange. It makes the text more interactive.

Sharma once said, “The fact that emotions are both compelling and ordinary hold the reader inside the narrative and, since everybody dislikes and everybody feels anxiety, the emotions keep the narrative from becoming about something that is alien to the reader.” Having to “unpack” feelings in fiction presupposes that feelings are complex, and while this may or may not be true, what makes feelings resonate is their simplicity. They are compelling because they are ordinary; rather, we are compelled by other people’s feelings because those feelings are common—they are shared.

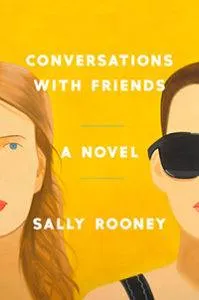

I thought about this while reading Sally Rooney’s novel, Conversations with Friends, which consists of remarkably simple prose but is nonetheless compelling in its ordinariness. The novel, which is somehow both quiet and forceful, is about two twenty somethings who listlessly float through their lives, having affairs, reading poetry, being British. And even though she’s British, the narrator, Frances, has a lot of feelings, which she relays to readers by saying “I felt.” Frances has no idea what she’s doing, but she does know what she’s feeling, and this explicitness helps guide us through the story. (In one exchange, Frances tells her friend, “I just feel.”)

I thought about this while reading Sally Rooney’s novel, Conversations with Friends, which consists of remarkably simple prose but is nonetheless compelling in its ordinariness. The novel, which is somehow both quiet and forceful, is about two twenty somethings who listlessly float through their lives, having affairs, reading poetry, being British. And even though she’s British, the narrator, Frances, has a lot of feelings, which she relays to readers by saying “I felt.” Frances has no idea what she’s doing, but she does know what she’s feeling, and this explicitness helps guide us through the story. (In one exchange, Frances tells her friend, “I just feel.”)

I feel like being unafraid to begin sentences with “I felt” or “She felt” gives me freedom as a writer. I feel like, as a reader, coming across a sentence that begins with “I felt” or “She felt” makes it easier to identify with the character or narrator. I feel like the prose becomes more raw, more honest. Being in the world is so often confusing; I feel like “I feel like” helps me sort it out.