New Adult, Young Adult? What’s the difference?

Though I’ve ardently and consistently loved books since I was old enough to hold one (and thus long before I could read one), it’s only in the past few years that I’ve become interested in the process of making one. How it gets represented, edited, sold, marketed and somehow lands on my bookshelf thanks to thousands of hours of labour. I like books just because they exist, a doorway that opens to adventure every time without fail.

What this means is that I like all manner of books. Fiction, sci-fi, fantasy, romance, historical fiction, memoir, essays, travel, sport, graphic novels — I’ll even admit to having some textbooks on my shelves, which are about subjects I have never studied. I like to think I know plenty about genres, but the concept of New Adult has only arrived to me in the last few years.

I had heard the term bandied about a bit among book lovers, especially those in the United States. I live in the United Kingdom, where the term doesn’t seem to carry the same weight with readers, but the books produced from it are nonetheless popular. I hadn’t really understood its practical meaning until I read Sarah J Maas’s A Court of Thorns and Roses. I knew during my read that it was different to the young adult fantasy fiction series I had read before. It was darker, sexier, grittier…but it wasn’t what I’d consider ‘adult’ either. Suddenly ‘new adult’ made a lot more sense.

I’m no expert, but here’s what I’ve managed to work out. New adult fiction features protagonists who are 18–25, maybe even a little older, so you won’t find Katniss Everdeen here. From my research, it seems that many of the early new adult sensations were in the romance genre, but this is expanding as the years pass. Where YA might deal with issues facing young people, new adult will look a little father ahead to significant moments of transition for characters who are adults needing to find their place in the world — thinking about leaving home and family, or getting a job, or embracing being the chosen one to rule the world.

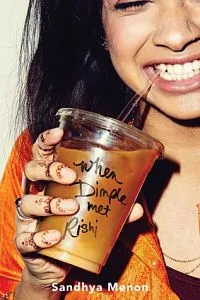

Of course, lots of these things happen in adult fiction too, as well as the more traditional YA we all love so much, so the difference is still a bit of a strange one to tie down. Arguably it’s all about the perspective of the protagonist. No longer a child but not entrenched in the adult world just yet, these protagonists are the voices which can often slip through the gaps in the real world. When I was heading off to university, I don’t remember any books with characters that shared my fears and goals, though more recently in my last twenties I read Rainbow Rowell’s Fangirl and my former new adult heart definitely skipped a beat. In the same vein, I was so excited for Dimple from When Dimple Met Rishi by Sandhya Menon, as she sets out to explore the world outside the expectant walls of her family.

I got the same vibe from Things a Bright Girl Can Do by Sally Nicholls, which explores themes of resistance, suffrage, and same sex relationships during the years of World War I in Britain. It was emotionally deeper than the war stories I read as a kid and I can’t imagine any adult shrugging it off either. And I loved Julie C Dao’s Forest of a Thousand Lanterns, which casts aside the traditional ideas of heroism in favour of a female antihero who seeks greatness.

As with all things, there are detractors. When it first emerged, Publisher’s Weekly questioned if a readership existed for books in the genre — a question which patently ignores the fact that the recent decades of human history have ensured that there is no set path from childhood to adulthood, and no easy solution to ‘just growing up’. Though new adult started out with romance stories, it’s already widened significantly.

The real issue with new adult is that, ironically, it’s young and needs space to grow. There isn’t nearly enough diversity, and while proponents of it (like me) say that it can tell stories for people who are neither child nor mortgaged adults, the reality is that many of the stories carrying the tag aren’t quite as gritty and ‘real’ as I might like.

A dearth of real human issues, from racism to immigration, disability, sexuality and even climate change, remains the problem. Those are the lived experience of new adults, and the development of the genre demands diversity if it is to survive and become a banner-bearer for an entire generation.