8 of the Most Infamous Literary Hoaxes

Content notice: discussion of racism, war, suicide, and substance abuse.

Literary hoaxes and frauds are shocking, tragic, and enraging. They take several forms. Some are forgeries that attribute the writers’ words to more famous authors. Others claim the work is much older than it really is—perhaps ancient. Some hoaxers intend to satirize or prank the literary world, exposing people they consider insincere, untalented, or gullible. Literary hoaxes can even have ironic results, especially when contempt is a motive. Instead of discrediting styles or people the hoaxer dislikes, pranks can make the targeted styles even more influential. Because literature is subjective, people always read what they want into it, even after frauds have been revealed.

This is a rare Book Riot list composed entirely of white authors, mostly men. I discussed my reasons for this choice with my editors. Racism is integral to many literary deceptions. Some white authors make up a false persona of someone who is a person of color. As Hua Hsu wrote in 2015, some white writers may mistakenly assume it’s easier for authors of color to get published. There are those who also undermine authors of color’s work for racist reasons, which might be unclear to me as a white writer.

The authors on this list either admitted to their hoaxes, or evidence showed obvious plagiarism or anachronisms. Some of them even preyed on readers’ desire for diverse literature. Meanwhile, barriers to marginalized authors remain in place. Often, the hoaxers are well-connected in the publishing industry. Hoaxes confirm their authors’ and readers’ stereotypes, reinforce marginalized people as “the Other,” or spread disinformation.

Some of these books were pulled or destroyed. This is for informational purposes only: while I’m not recommending or linking places to buy or read them, I do recommend reading more about the hoaxes themselves and criticisms of them. Although most people probably know they’re fake, some of these works could still spread dangerous, racist misconceptions, or disinformation about drugs or history, even today.

Thomas Rowley, 1770

Thomas Chatterton was a brilliant young English writer who wrote poetry as a child and was a lawyer’s apprentice when he was only 14. Using medieval parchment, he wrote poems and passed them off as the writing of a fictional medieval monk named Thomas Rowley. After Horace Walpole exposed Rowley’s poems as Chatterton’s forgeries, Chatterton killed himself at age 17. Romantic poets, including John Keats and William Wordsworth, praised Chatterton and were influenced by him long after his death. In the 19th century, Pre-Raphaelite poets and painters created a pseudo-medieval style, also partly inspired by Chatterton.

The Cottingley Fairies, 1917

In the English village of Cottingley, two cousins, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, created images of fairies that they claimed were real. The girls were skilled artists who copied illustrations from Princess Mary’s Gift Book, added wings to the figures, and photographed the cutouts outside. Three years later, in 1920, Arthur Conan Doyle wrote an article called “Fairies Photographed,” bringing them more widespread attention. Doyle believed the photographs were “the evidence for fairies,” as he titled a 1921 follow-up article. Wright and Griffiths finally admitted to the hoax in 1983. Today, it might be hard for us to fathom an educated person like Doyle believing these images were real. However, Doyle also supported the Spiritualist movement, which promoted belief in mediums who could contact, or even photograph, ghosts.

Ern Malley, 1944

Two Australian poets, James McAuley and Harold Stewart, tried to prove Modernist poetry was terrible by intentionally creating “bad” poetry. Of course, art is subjective, so their plan backfired. They used rhyming dictionaries, The Complete Works of Shakespeare, and even a US report on mosquitoes to combine random phrases into nonsense. Then, they made up a tragic poet figure, Ern Malley, who had died very young. They sent “Malley’s” manuscript, The Darkening Ecliptic, to editor Max Harris, who devoted an entire magazine issue to them. McAuley and Stewart later admitted to their hoax. Modernist writers, especially the Dadaists, intentionally created nonsense because they found the violence of World War I inexpressible and meaningless. Ironically, trying to discredit Modernism, McAuley and Stewart captured its appeal during another World War. The techniques of pastiche and found poetry are still popular today.

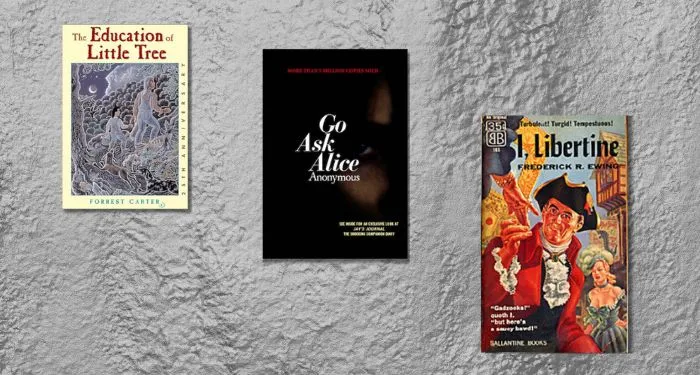

I, Libertine, 1956

Jean Shepherd, an American writer and radio host, expressed contempt for booksellers and bestseller lists on his show. He thought some readers liked whatever other people told them to like, rather than thinking for themselves. He decided to prank the public, with his listeners in on the joke. Shepherd convinced his audience to go to bookstores and request a novel that didn’t exist. One listener suggested the title I, Libertine. The nonexistent book was historical fiction by Frederick R. Ewing, set in the 18th-century British court. Ironically, the stunt created demand for a real book. This hoax showed that some people would rather pretend to be in the know than admit ignorance. Shepherd admitted to the hoax in The Wall Street Journal in August 1956. Still, Ballantine Books published I, Libertine the next month, co-written by Shepherd and Theodore Sturgeon. Shepherd’s other stories were later adapted into the 1983 movie A Christmas Story.

Go Ask Alice, 1971

This book was published as a found document: supposedly the diary of “Alice,” a teen girl who died soon after trying LSD and other drugs. Its author, Beatrice Sparks, called herself an editor who “found” the diary. She also sometimes fraudulently posed as a psychotherapist, according to Rick Emerson’s 2022 book Unmask Alice. Emerson wrote that Sparks’ books contributed to the War on Drugs of the 1980s and beyond. As Jonathan Russell Clark wrote, the book sometimes appeals to loved ones of people with substance use disorder, but offers only rumors and misinformation. In August 2024, I noticed Go Ask Alice for sale on Amazon. The cover says it’s “Anonymous” and part of the “Anonymous Diaries” series. This is deceptive marketing that might make some readers mistake it for nonfiction.

The Education of Little Tree, 1976

This book by Forrest Carter, about a Cherokee boy living with his grandparents, was first published as an autobiography. Republished over 10 years later, it became a bestseller and a popular choice in schools and book clubs. It was adapted into a movie in 1997. However, “Forrest Carter” never existed. He was the pseudonym of Asa Earl Carter, a former segregationist and KKK member. Carter was not Indigenous and even made up fake Cherokee words in the book. In 2000, Daniel Heath Justice, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, criticized the book’s cultural appropriation and racist stereotypes in his journal article, “A Lingering Miseducation: Confronting the Legacy of Little Tree.”

“Hitler’s Diaries,” 1983

In 1983, the West German news magazine Stern purchased 60 volumes from Konrad Kujau, who claimed they were Adolf Hitler’s diaries from World War II. Stern sold serial rights to international outlets, including London’s Sunday Times. Many journalists and historians immediately raised suspicions, noting discrepancies with verified historical records. Hitler likely didn’t even keep diaries! Kujau later admitted to forging the diaries, which he aged by staining them with tea leaves. Kujau and Gerd Heidemann, the reporter who bought the documents from him, were both convicted of theft and fraud. This was not only a forgery, but also dangerous disinformation about Hitler and the Nazis. It also damaged the reputations of the news outlets.

Araki Yasusada, 1991

Around 1990, American Poetry Review and other literary journals published poems by “Araki Yasusada,” who had supposedly survived the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, then died in 1972. The magazine Lingua Franca later exposed that Yasusada had never existed. His biography and poetry were filled with blatant anachronisms (like the words scuba and crematorium), and no photos of him were ever found. Most critics think Kent Johnson, a white, American poet, was the creator of “Yasusada” and his poems. Johnson, who died in 2022, gave cryptic answers when asked whether he created the hoax. By pretending to be a Hiroshima survivor, the writer appropriated and diverted attention from real, first-person accounts of Hiroshima survivors.

Further reading:

I recommend Yellowface by R. F. Kuang and Erasure by Percival Everett, both brilliant novels by authors of color that satirize literary frauds. Erasure was adapted into the movie American Fiction last year. In both stories, author characters go to great lengths to maintain their façades and give the publishing industry what it apparently wants.

In 2021 for Book Riot, I analyzed Orson Welles’ The War of the Worlds broadcast, which some people mistook for a real invasion.