On Miss Cackle’s Academy for Witches

Kaite Welsh is an author and journalist living in Edinburgh, Scotland where she writes about culture, feminism and LGBT issues. Her work has featured in The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and Cosmopolitan and she is a regular guest discussing culture and politics on BBC TV and radio. The Wages of Sin is the first in the Sarah Gilchrist mysteries, featuring a female medical student in Victorian Edinburgh.

Twitter Handle: @kaitewelsh

I have a sneaking suspicion that, if I examine them closely enough, all my major life decisions have been influenced by books. My choice of career—author and literary critic—is the obvious one, but then there’s my teenage decision to dye my hair red because of that one line in Sylvia Plath’s ‘Lady Lazarus’, the countless tattoos I plan and then chicken out of getting and even the spelling of my name, stolen from a library book after I decided that just plain ‘Kate’ was too dull.

But when it came to choosing a high school, rather than go to the closer non-religious girl’s grammar, I—a girl whose Catholicism began and ended with my baptism and who would accidentally take my first Holy Communion in her first term because no one had explained to me what happened in Mass—ended up at a convent school filled with nuns, crucifixes and seemingly arcane rituals, there’s no denying that it was influenced by getting as close as I could to my dream school—Miss Cackle’s Academy for Witches.

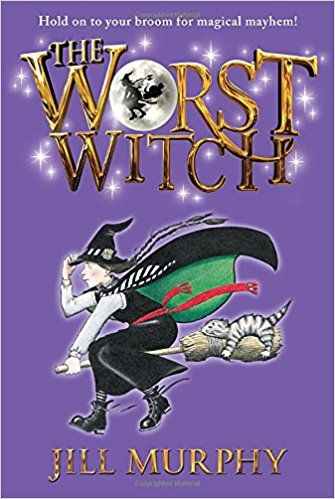

I first read The Worst Witch, Jill Murphy’s beloved tale of inept pupil Mildred Hubble’s adventures at a witching school, when I was around seven, and have been coming back to the series sporadically ever since. I recently bought the first book for my niece’s sixth birthday, a sign that I should have outgrown my comfort reading long ago; but I can’t quite leave Mildred—with her broken broomstick, trailing bootlaces, tabby cat instead of the traditional black cat, and a fear of the dark—behind.

I first read The Worst Witch, Jill Murphy’s beloved tale of inept pupil Mildred Hubble’s adventures at a witching school, when I was around seven, and have been coming back to the series sporadically ever since. I recently bought the first book for my niece’s sixth birthday, a sign that I should have outgrown my comfort reading long ago; but I can’t quite leave Mildred—with her broken broomstick, trailing bootlaces, tabby cat instead of the traditional black cat, and a fear of the dark—behind.

Although I was an academic child, closer to snobby mean girl Ethel Hallow than Mildred in terms of my grades, I was still a walking disaster thanks to poor spatial awareness and a constant tendency to daydream rather than concentrating on my work. In retrospect, both she and I have inattentive ADHD and probable dyspraxia, but at the time it was just a relief to find my more hated traits reflected in a series I loved. It was also the place I found my first literary crush, although it would be years before I realised that’s what it was, in the form of the austere Miss Hardbroom, thus leaving me with a lifetime tendency towards falling for emotionally repressed women who appear and disappear without warning.

And then, at eleven years old, I stumbled into a world so unfamiliar to me that it may as well have been fictional. Upton Hall Convent School stood not perched perilously on a mountain top like Cackle’s, but just off a roundabout in a quiet suburb of North West England. A former boarding school whose science labs were converted dormitories, it was full of oddities like St Anthony’s Passage, the tiled little tunnel that ran from the dining room to the science buildings, classrooms full of crucifixes depicting a bleeding Jesus on the cross, and the piece de resistance: tucked away next to the hockey pitch was the school graveyard. Buried nuns, a private chapel and mysterious woods we were forbidden from entering—where else was I going to go?

The similarities between a convent school and Cackle’s Academy aren’t accidental—Murphy was inspired to create Mildred and her world while at an Ursuline convent in South London, surrounded by severe black-clad women chanting in Latin with a list of arcane rules she could never quite follow.

It was an odd choice for me—even then I knew I was a feminist and was pretty sure I was both queer and pagan, but after Cackle’s, the school seemed far more familiar and safe than the larger, more conventional options on offer. After that, it was pretty inevitable I’d have a goth phase and even more inevitable that I’d go on to write “enthrallingly gothic” novels where ambitious single women navigate complex desires within repressive, patriarchal social structures.

It was such a strange, enigmatic place that even now I can’t quite identify what really happened and what was the product of an overactive imagination. I have a very clear memory of seeing Soeur Marie Madeleine Victoire, the Foundress of the order, being exhumed from the graveyard in my first year, although Google informs me that this took place a good decade before I arrived. Perhaps it was another nun, or perhaps I can imagine it so vividly because it’s the exact kind of thing that would have happened there. Still, the last body to be buried there was in 2007 and I can still remember the names chiselled into the sandstone plaques—Mother Assumption Slaughter, Sister Euphrasia Shields, Mother Mechtilde Delant. They live on, tucked away in a notebook and ready to resurrected for a future novel.

These days the school has expanded and even the old corridors seem lighter, airier. Change has been slower to reach Cackle’s Academy—a new BBC/Netflix adaptation might include modern technology but there are enough spell books and eye of newt to satisfy even the most accident-prone of witches. And while I may have passed the metaphorical baton on to the next generation, I still have my old copies on my desk, next to my altar and tarot cards. I even have a black cat—and, in a nod to Mildred’s beloved Tabby, one of those as well, although I’m rapidly sliding down the scale from ‘probable witch’ to ‘crazy cat lady’.

There’s a tradition in school leaving assemblies—the closest thing Britain gets to a U.S.-style high school graduation—for pupils to be reminded that when they go out in the world, they will always carry part of their school with them. Even in my thirties I find myself remembering this at the strangest of moments and, although I never attended Miss Cackle’s school outside of my imagination, I think she’d be proud of how I turned out.