Lesser Known Queer Literary Icons

With censorship and bans ping-ponging across the U.S. at a horrifying rate, queer people can’t just do their jobs and live their lives. There is no sitting on the sidelines for us, instead, we have to be activists in a forever battle for our rights. This was also true of our historical figures, many of whom had to announce their queerness amidst even more toxic environments than that of our current trashfire situation. In the case of queer literary icons, they didn’t just write or publish, but also hustled to get their work read in a world trying to silence them.

I have studied LGBTQ+ history and pop culture for most of my adult life, so I chose four people whose names hadn’t turned up in the 20 years I’ve been consuming all manner of gay media. Again, it doesn’t mean they aren’t famous figures in their own right, each of them are, but somehow they’ve snuck under the radar of mainstream queer history. It was only a year ago that I discovered Nobuko Yoshiya and, though she is certainly very famous in Japan where there is a museum dedicated to her, she did not have the breakthrough fame of other authors who populate our LGBTQ+ literary canon.

Truly, learning only recently about many of these queer literary icons makes me question how English and Creative Writing is taught — why did people have me reading Joyce and Hemmingway for the 43rd time but not a single work by any of the people listed below? My queer-story-obsessed self didn’t learn about them until I was actively looking for LGBTQ+ literary figures whose names I didn’t recognize. That is nuts, but I am glad that I finally have found them and can now share them with you.

Al-Hakam II

Al-Hakam II is the only non-author on this list. The second Arab Caliph of Córdoba, featured in Sarah Prager’s Rainbow Revolutionaries: 50 LGBTQ+ People Who Made History, was behind the construction of an essential and very grand library. He also led Al-Andalus, the Muslim-ruled part of the Iberian Peninsula, and successfully made peace with the Catholic kingdoms of northern Iberia. His reign began when he was 46 and lasted a short period of only 16 years from 961-976.

Born in 915 to Abd-ar-Rahman III and Murja, that’s basically the extent of what is known about his early life. He oversaw the construction of many beautiful buildings, including an enormous library. His library might have contained more than 400,000 books (unconfirmed, but you know, ballpark amount). He also was responsible for a vast translation of written works, from Latin and Greek into Arabic, and his big ol’ library employed a ton of people.

Apparently, there were rumours that he had an all-male harem. Problematic, of course, when you are eventually expected to have an heir. Ultimately, he gave in and married — the story goes that Al-Hakam married a concubine named Subh, but then nicknamed her Jafar, a masculine name. Also, Subh is said to have worn short hair and male-styled pants and, while some people suggest that she did this to be taken seriously by the mostly male court, I give that some very skeptical side-eye.

Alain Locke

Education and Activism

Born on September 13, 1885, Alain (née Arthur) Leroy Locke grew up in Philadelphia. According to Alain Locke: Faith and Philosophy, Locke was one of very few undergraduates who attended Harvard University and he was the first Black Rhodes Scholar. Despite that honour and the fact that he graduated magna cum laude, five Oxford colleges rejected him. Hertford College eventually accepted Locke, and later on, he’d receive an assistant professorship position in English at Howard University. At Howard, he taught race relations but then got fired for fighting for equal pay for Black faculty; luckily short-lived, he was rehired a year later by Mordecai W. Johnson, the first Black president of the university. He remained a professor there until retiring.

Literary Historian

Alain Locke wrote mostly academic writing from a philosophical bent, with a long list of books, reviews, and articles to his name. One of his best-known works was The New Negro, a collection featuring seminal essays authored by himself and other Black authors. In 2020, it was republished as Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Though his writing was all academic nonfiction, he was a mentor to many of the authors of the Harlem Renaissance.

Unfortunately, due to the discrimination of the time, Locke did not live an out life. Leonard Harris, Locke’s biographer, explains that Locke exchanged romantic letters with men but lived a very secretive existence.

While Locke doesn’t have the instant and far-reaching name recognition of Harlem Renaissance figures like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, his influence remains. In 2020, Dr. Ann Olivarius, a Rhodes scholar and lawyer, named Locke alongside Zambian civil-rights activist Lucy Banda-Sichone as the two figures who should replace Oriel College’s controversial statue of Cecil Rhodes, a British imperialist.

Pat Parker

Writing Poetry

Born in Houston but eventually settling in the Bay Area, Pat Parker (originally Patricia Cooks) was an American poet and activist. Much of her poetry deals with poverty and domestic violence, and she was open about her life experiences with those topics. She was married twice — once to Ed Bullinsmen, a playwright and Black Panther who abused her, and then to author Robert F. Parker. In the 1960s, she divorced Parker and came out. Parker had two daughters and her poetry fought back against the idea that lesbians couldn’t be proper parents.

Unfortunately, she died far too young at 45, but had an acclaimed career that saw her as an essential part of the founding of the Black Women’s Revolutionary Council and the Women’s Press Collective. She has five published poetry collections: Child of Myself (1972), Pit Stop (1975), Movement in Black (1978), Womanslaughter (1978), and Jonestown & Other Madness (1985). She recorded an album, Where Would I Be Without You (1976), alongside fellow lesbian poet Judy Grahn.

Activism

Her activism wasn’t only through poetry. Between 1978-1987, Parker was director of Oakland’s Feminist Women’s Health Center. She also took part in political activism and even worked alongside the United Nations. In 1985, for instance, she travelled with delegations to Kenya and Ghana before testifying to the United Nations about women’s status in those countries.

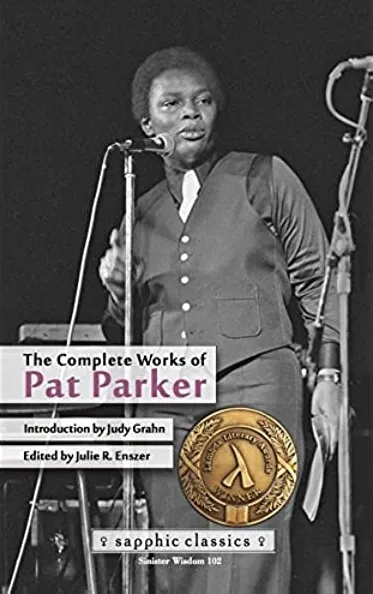

Her poem “My Lover is a Woman” is absolutely heartbreaking, filled with nuance, intensity, and gorgeously vivid imagery. It’s also an incredible ode to her activism, dealing with issues of civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights. In 2016, Sapphic Classics published The Complete Works of Pat Parker (2016) — until then, her work had been out of print for 20 years. New York City’s Stonewall Inn celebrated Parker in 2019, adding her to the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor as one of its “pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes.”

Other remaining tributes include Pat Parker Place, a community center in Chicago, and The Pat Parker Poetry Award, which is awarded to Black, feminist lesbian poets.

Elana Dykewomon

Born Elana Michelle Nachman, she was born in Manhattan, but her family moved to Puerto Rico so that her father, a lawyer, could open a practice. Her mother worked as a researcher for Life magazine and later became a librarian in Puerto Rico.

Essential Works

Although 1974’s Riverfinger Women was the first lesbian book advertised in The New York Times, Dykewomon’s five-decade-long career never went fully mainstream. Her other works include 1997’s Beyond the Pale, a novel about Russian-Jewish immigrants, as well as many short stories and poetry collections: They Will Know Me By My Teeth (1976), Fragments from Lesbos (1981), Nothing Will Be As Sweet As The Taste: Selected Poems 1974–1994 (1995), Moon Creek Road (2003), What Can I Ask: New and Selected Poems 1975-2014 (2015). She was also a prolific article writer and essayist.

Beginning in 1987, she had a seven-year run as an editor of Sinister Wisdom, the lesbian literary which still exists to this day. She was also one of the organizers of the San Francisco Dyke March.

The author was still publishing under her birth name until the early 1980s, after which she chose a pen name to make a pointed, political statement: Dykewoman, eventually shifting a letter to become Dykewomon. Dispatches From Lesbian America, a 2017 anthology of essays, had a piece written by her that explained, “I chose ‘dyke’ for the power and ‘womon’ for the alliance,” she wrote in an essay published in a 2017 anthology, “Though not religious, she identified strongly with her Jewish background.” An obituary in The Times of Israel quoted her as having joked, “If I had to do it all over again, I might have chosen Dykestein or Dykeberg.” Personally, I love that on many levels.

So there you have it, there are always more queer icons to find out about. Interested in learning about other lesser-known queer historical figures? This post is where to go next. Keep learning.