In Appreciation of Sir Terry Pratchett

It’s been three years since Sir Terry Pratchett left us much too early at the age of 66, surrounded by his family and his cat at his home in England. Pratchett was and remains one of the great pillars of modern writing. In terms of reach, world-building, or simply quality of his prose and characters, few reach the heights he managed in his long career that spanned nearly 70 books. This career included of course the immortal Discworld Series, spanning 41 books, but also excellent work for children and teenagers, as well as biting and incisive agitprop, lectures, editorials, and other nonfiction; something not often accomplished by writers who get classified as mere “genre” authors, a distinction he fought tooth and nail with his characteristic feistiness.

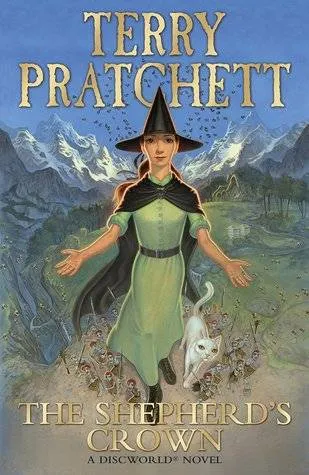

This April, Sir Terry would have turned 70 years old, and based on his productivity would have given us many more wonderful works in and out of Discworld. As he said, “No one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away.” Even though he has left us, his ripples have not. The final Discworld book, The Shepard’s Crown, was published posthumously and was a fitting, touching conclusion to the series, and the 2017 BBC2 produced–documentary Back in Black offered closure to fans clamoring for a never-finished memoir. The future offers even more promising work in the pipeline. Mort, the fourth and one of the most influential Discworld novels, is reportedly being produced for a feature film adaptation written by Terry Rossio.

Even though he has left us, his ripples have not. The final Discworld book, The Shepard’s Crown, was published posthumously and was a fitting, touching conclusion to the series, and the 2017 BBC2 produced–documentary Back in Black offered closure to fans clamoring for a never-finished memoir. The future offers even more promising work in the pipeline. Mort, the fourth and one of the most influential Discworld novels, is reportedly being produced for a feature film adaptation written by Terry Rossio.

Perhaps the biggest news recently is a BBC- and Amazon-produced adaptation of Pratchett’s sensational collaboration with one of the other great minds in fantasy, Neil Gaiman. Gaiman himself (of American Gods fame) is writing and acting as show runner for a six-part Good Omens series coming in 2019. The series has wrapped primary filming as of March 2018 and will feature a sensational cast including David Tennant, Michael Sheen, and Jon Hamm. The show is also being produced by Pratchett’s longtime assistant and friend Rob Wilkins, and was allegedly a posthumous wish from Pratchett to his friend Neil Gaiman, who has approached the project with vigour and care befitting his close relationship with Sir Terry.

With all these exciting projects on the horizon, what does the man’s words and legacy mean in 2018? A world feeling increasingly divided, cynical, and with technology seemingly increasing this divide by disruption of traditional life and creating information bubbles online? We need a fantastical satirical lens that steps back from our everyday experiences more than ever.

Personally, Sir Terry was important to me. He was, along with Tolkien, the author that made me a reader and a librarian who takes a stab at writing in his free time. It was his humor, his heart, and his characters that drew me in. It felt like Dickens in a fantasy world, taking aim at social ills through massive mainstream popularity with his unique brand of moral outrage. He taught me to question, get angry, but never give up. He was affable and good natured, but did not suffer fools. Sam Vimes made me righteous, and Small Gods taught me to question things with my own critical eye.

Pratchett was a humanist in the vein of Kurt Vonnegut, never failing to believe in humanity’s capacity for screwing up or doing good. His work often involved heavy material like death, oppression, sexism, and poverty. Characters that would cause problems by simply acting like humans: good, bad, or indifferent. However, his work wasn’t cynical. It didn’t discard people, it expressed a hope in the potential of people and what they can do as he poked fun at our foolishness and worst impulses. Throughout 41 Discworld books and all the others he wrote outside of Discworld, he took on every issue humans confront in our society and our lives, and these are issues that need to be addressed today, maybe even more so. Sexism, prejudice, populism, snobbery, and education: he tackled them all with a heart of gold and a seething anger at unfairness.

Despite this, it wasn’t preachy. It was aggressive empathy on and off Discworld. Pratchett understood why people could make mistakes but still be worthy of respect, or disagree with someone likewise. The villains in Discworld may be misguided individuals that we can see aspects of ourselves in, and are rarely flat-out “evil” for the sake of storytelling convenience. He even made death itself an empathetic character. Death, the ultimate enemy of mankind, was far from a simplistic “evil” character on Discworld. He enjoyed curry, cats, and would indulge people’s last wishes and questions.

Pratchett famously was an atheist, or at least an agnostic humanist. And while he poked at organized religion in his writing, he again always treated the characters involved as full humans who had their own experiences and reasons for believing in whatever they chose. While he wrote ethics that came from characters and societies trying to share the world together, such as in his Carnegie medal–winning “Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents,” wherein the rodents come up with morality before belief.In our increasingly divided world, we need these ideas. We need this perspective and this train of thought. We all need to be firm thinkers and have our values and perspective, but also keep our empathy and remember that we are dealing with other real humans who feel, hurt, and love just as we ourselves do. Be firm, thoughtful and kind, and campaign against wrong. We should all strive to be more Terry.