Why It’s Important to Keep Reading Books By People Even If They’re Monsters

While we at the Riot are taking this lovely summer week off to rest (translation: read by the pool/ocean/on our couches), we’re re-running some of our favorite posts of 2014. Enjoy this Best Of, and we’ll be back to your regularly scheduled programming on Monday, July 7th!

This post originally ran January 23rd.

____________________

I know we’re not supposed to admit to having favorites, but I’m going to do it anyway: Kit is one of my favorite writers here at Book Riot. Whenever she posts a new article, I’m excited to see how she’ll go about challenging me and entertaining me this time. Which is exactly how I felt when I started reading her excellent piece, “No, I Won’t Read Your Book If I Think You’re A Monster.”

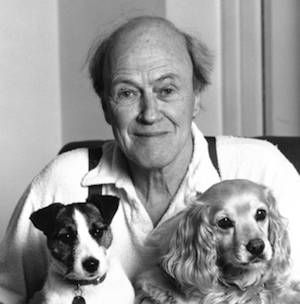

In this piece, Kit describes her very personal reasons for choosing not to read books authored by people who’ve committed inhumane crimes. She mentions Woody Allen, whose former stepdaughter came forward to say that he molested her when she was 7 years old; J.D. Salinger, who had skeevy relationships with teenage girls; Orson Scott Card, who’s aggressively homophobic; and Roald Dahl, who supported Hitler hated Jews. Kit’s conclusion, which I wholeheartedly support as her personal choice, is: “I’m not going to read your book if I think you’re a monster. I’m not going to know what I know and still support you.”

Me, though, I’m going to keep reading them. And I don’t even feel uneasy about it, not even a little bit. In fact, I think it’s incredibly important.

When I choose to read a book, it’s not because I agree with the author 100%. It’s not because they’re just like me or because I’ve judged them to be a good or flawless person. Reading a book by someone isn’t my “vote” for that person as a human being.

For me, the most rewarding reads are the ones that make me uncomfortable because they challenge my worldview or philosophy, expressing beliefs that go beyond my personal comfort zone. This is why I’m attracted to dark and twisty reads, and why my favorite heroes are really antiheroes with ambivalent motives and duplicitous hearts. I value these murky zones in literature because they most honestly reflect the terrible truth of human nature. I read both the good and the evil because I want to know what it’s like to be human — not just for me, but for everyone else who is human, too — even the ones with darkness and evil inside. Which is all of us, in a way. (We’re all both the princess with the golden ball and the ugly troll under the bridge, after all.) I’m hungry to know it all, and when I read it’s as an observer of the human condition, not a judge.

I grew up in a religiously conservative family who taught me that things like birth control and homosexuality were evil, and that dark skin was God’s curse. These were the only values that I knew. I credit my secret inner life curled up under the covers with a flashlight and book for teaching me to question those values. Reading books by people with whom I vehemently disagreed helped me learn to examine my beliefs from every angle and see if I still thought they held true. In some cases — see: homophobia, sexism, racism — thank god I changed my mind. In others, thank god I didn’t. But even when my values have held fast, I’ve still been grateful for the exposure to beliefs that make my skin crawl. Because otherwise how will you ever know what you don’t know?

I once had a teacher who was fond of saying that he’d rather know his enemies; be able to see them face-to-face. It’s an ancient belief, as it happens, often cited in relationship to Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. And me? I will keep reading Woody Allen, J.D. Salinger, Orson Scott Card, Roald Dahl, and all the other monsters — not from an uncomfortable place of “hate the artist, love the art” — but precisely because they are the enemy.

I’d rather know what we’re up against instead of looking away or sweeping it under the rug. In return, we gain wisdom about ourselves, our own values, and human nature itself. This is the very best thing about reading.

In their own small way, monsters can be gifts.