If You Love the Book, Do You Really Care What Got Lost In Translation?

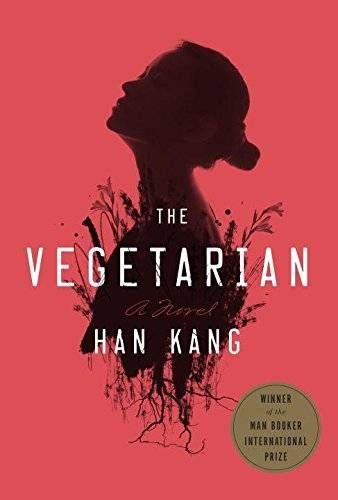

Rebecca & Jeff have been discussing translations on the last two episodes of the Book Riot podcast. Specifically, they’ve been talking about recent news regarding Deborah Smith’s translation of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, a novel which won the Man Booker International Prize in 2016. According to one report, 10.9 percent of the first part of the novel was mis-translated and 5.7 of the original text cut from the English version entirely. More offensive, apparently, is the fact that Smith changed the prose – employing a style more elaborate than the author’s.

For the past several years, translations have been a large part of my reading life. And when presented with an awkward sentence or a strange choice of adjective I’ve wondered whether the translator might have made a mistake. I’ve also been delighted to “discover” a new favorite writer only to change my mind after reading a second book, done with a different translator. But, ultimately, whether the book I’m reading is the exact book the author wrote is and has always been a complete non-issue for me. I don’t care. Not even a little.

Because there’s really no point in caring. I (and I imagine most of you ) will never read a book written in Korean, Chinese, Arabic, French, Persian, German, Spanish, or any of the thousands of languages spoken around the world unless it’s been through the hands of a translator. In case I’m not making myself clear – I can only read English. So I do not have the luxury of quibbling. The only version I will ever have access to of, say, Sergio Pitol’s The Magician of Vienna, is the one currently on the table next to me which has been ably translated by George Henson. There will be no line-by-line comparisons. No concern over whether a tone other than the author’s has been projected by George onto the original prose. There are more important things in life than whether he substituted a lemon for a lime (o the humanity) on page 35. All I need are the words as they appear on the page. And if they move me, excite me, make me laugh or cry, what does it matter that they are the product of a collaboration rather than a single voice? I’ve absolutely no idea how I feel about El Mago de Viena, published back in 2005. But I love the English translation so much I’m on my second reading. And why shouldn’t I? It, too, is a book that exists in the world.

I have not read The Vegetarian, but the question it raises is an old one. What is getting lost in translations? Are readers experiencing the same book as their counterparts in China, France and Spain? Does the translation meet some arbitrary “purity” test, or has the translator through the very act of translating somehow contaminated the original text? This is the reason some publishers do not put the translator’s name on the cover of the book and the reason some readers say they aren’t comfortable reading translations.

For the record: it’s almost technically impossible to do a true word-for-word translation from one language into another… at least one that anyone would want to read. (Check out Deborah Smith’s Asymptote essay on translating just the title of Han Kang’s Human Acts for a fascinating look at the difficulties involved). There are also cultural differences to be considered. But what does that really mean for the reader? I’ve attended panels of authors and their translators where the author told the crowd how awful they felt when the translator was criticized for supposed poor word choices – when it was actually the author’s own choices being criticized. I’ve also listened while a translator explained how they’d been conflicted about a section of a work that they felt was racist and their subsequent relief when the editor made the decision to cut that section out of the translated book entirely. I once even read on a forum that a certain writer’s novels weren’t very good in their original language. Their English translations were a huge improvement.

This is not a situation exclusive to literature. Foreign films and television shows are re-made. Songs are covered. We accept these reinterpretations without a second thought. Why then do we treat books differently? Of course we must expect a level of competency and artistry from translators, but it’s silly to expect that some words and phrases won’t get sacrificed when moving from one language to another. Translation is a gift to readers – one that allows us to experience a world of stories and perspectives which would otherwise be closed to us. And if the finished product (however flawed) is a good book, who are we to look a gift horse in the mouth?

An old saying which, funnily enough, comes to us via a flawed Latin translation.