I Grew Up With Laura Ingalls Wilder. Here’s Why I Won’t Be Reading Her Books to My Son.

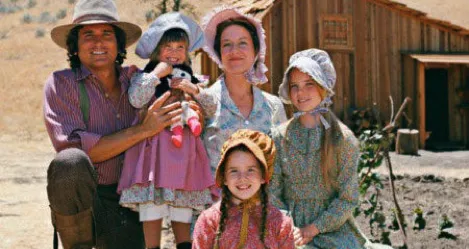

Bump into me in the mid 1990s and you’d have stared down at a girl in a calico dress and gingham bonnet who introduced herself as “Laura, like Laura Ingalls Wilder.” By the time I turned eight, I’d read all nine Little House books and cherished each minute spent in Laura’s world. If anyone grew up with Laura Ingalls Wilder in modern times, it was me.

I ached to live in the olden days, in a humble cabin swallowed by prairie grasses. I wanted to churn butter and sweep earthen floors and strip to my petticoat and bloomers to cool off in a swimming hole. I vowed that I would pass this adoration for pioneer days along to my future children by reading them the Little House books from infancy.

I ached to live in the olden days, in a humble cabin swallowed by prairie grasses. I wanted to churn butter and sweep earthen floors and strip to my petticoat and bloomers to cool off in a swimming hole. I vowed that I would pass this adoration for pioneer days along to my future children by reading them the Little House books from infancy.

Through my freshman year of college, I reread the books in order each year. When Pioneer Girl came out in 2014, I devoured every annotation. In 2017, I burned through all 640 pages of Prairie Fires in three days—even with a toddler at home.

But these two books did more than fascinate me: they peeled away at the Laura I thought I’d grown up with, revealing someone more nuanced and controversial than I would have understood or admitted in childhood. In Pioneer Girl, for example, I learned that the first edition of Little House on the Prairie contained this line on the first page: “There the wild animals wandered and fed as though they were in a pasture that stretched much farther than a man could see, and there were no people. Only the Indians lived there” (Pioneer Girl p. 3n7). For seventeen years, no white reader noticed the cruelty of these words. When someone finally complained to Laura’s editor, she agreed to edit the racist lines, with the concession that “It was a stupid blunder of mine” (Pioneer Girl p. 3n7).

It was more than a blunder; it was harmful, certainly to any Indigenous person who might’ve read it, and to every non-Indigenous person who in those seventeen years formed early racist ideas. The lines speak to the anti-Indigenous sentiments that creep through Laura’s books, persisting even today. The first page of the current edition of Little House on the Prairie reads, “They were going to Indian country. Pa said there were too many people in the Big Woods now” (Ingalls Wilder p. 1). These lines aren’t so different from those Wilder edited out of the first edition: There are too many people in the Big Woods, yet Pa is illegally moving his family onto land very much populated by the Osage people. The racism of the line might be less glaring, but it’s there.

And it gets worse. In the Little House on the Prairie chapter “Indians in the House,” two Osage men appear on the trail leading to the Ingalls cabin. After comparing the men to snakes with “glittering eyes,” Laura starts “shivering; there was a queer feeling in her middle and the bones in her legs felt weak. She wanted to sit down” (Ingalls Wilder p. 135). Then, positive that the men are hurting Ma and Baby Carrie (when really they are only taking some food from a house illegally built on their land), Laura says, “I’m going to let [the bulldog] Jack loose…Jack will kill them” (Ingalls Wilder p. 136).

Upon hearing that Laura even thought about doing this, Pa is angry with her. Still, he says—as though seeing an Indigenous person is like spotting a grizzly bear in the wild—“So you’ve seen Indians at last, have you, Laura?” (143). In just one chapter, Laura strips Osage people of their humanity and plots to kill them.

Yes, I adored these books as a kid. I cherish the memories of reading and loving them for so long. I grew up with Laura Ingalls Wilder, but it’s time to distance myself from her because I know more now. (As do larger literary organizations like the ALSC.) I understand that while these aggressions may seem insignificant to some readers, they are brutal values that I don’t want my son to absorb. I don’t want him to huddle next to the bulldog with Laura, thinking passionately about letting him loose to kill people simply because they are Osage and therefore automatically dangerous. The Little House books promote a racist and white-centered understanding of westward expansion. They pit young readers against the people whose land was stolen by pioneers like Pa and his family.

Through my freshman year of college, I reread the books in order each year. When Pioneer Girl came out in 2014, I devoured every annotation. In 2017, I burned through all 640 pages of Prairie Fires in three days—even with a toddler at home.

But these two books did more than fascinate me: they peeled away at the Laura I thought I’d grown up with, revealing someone more nuanced and controversial than I would have understood or admitted in childhood. In Pioneer Girl, for example, I learned that the first edition of Little House on the Prairie contained this line on the first page: “There the wild animals wandered and fed as though they were in a pasture that stretched much farther than a man could see, and there were no people. Only the Indians lived there” (Pioneer Girl p. 3n7). For seventeen years, no white reader noticed the cruelty of these words. When someone finally complained to Laura’s editor, she agreed to edit the racist lines, with the concession that “It was a stupid blunder of mine” (Pioneer Girl p. 3n7).

It was more than a blunder; it was harmful, certainly to any Indigenous person who might’ve read it, and to every non-Indigenous person who in those seventeen years formed early racist ideas. The lines speak to the anti-Indigenous sentiments that creep through Laura’s books, persisting even today. The first page of the current edition of Little House on the Prairie reads, “They were going to Indian country. Pa said there were too many people in the Big Woods now” (Ingalls Wilder p. 1). These lines aren’t so different from those Wilder edited out of the first edition: There are too many people in the Big Woods, yet Pa is illegally moving his family onto land very much populated by the Osage people. The racism of the line might be less glaring, but it’s there.

And it gets worse. In the Little House on the Prairie chapter “Indians in the House,” two Osage men appear on the trail leading to the Ingalls cabin. After comparing the men to snakes with “glittering eyes,” Laura starts “shivering; there was a queer feeling in her middle and the bones in her legs felt weak. She wanted to sit down” (Ingalls Wilder p. 135). Then, positive that the men are hurting Ma and Baby Carrie (when really they are only taking some food from a house illegally built on their land), Laura says, “I’m going to let [the bulldog] Jack loose…Jack will kill them” (Ingalls Wilder p. 136).

Upon hearing that Laura even thought about doing this, Pa is angry with her. Still, he says—as though seeing an Indigenous person is like spotting a grizzly bear in the wild—“So you’ve seen Indians at last, have you, Laura?” (143). In just one chapter, Laura strips Osage people of their humanity and plots to kill them.

Yes, I adored these books as a kid. I cherish the memories of reading and loving them for so long. I grew up with Laura Ingalls Wilder, but it’s time to distance myself from her because I know more now. (As do larger literary organizations like the ALSC.) I understand that while these aggressions may seem insignificant to some readers, they are brutal values that I don’t want my son to absorb. I don’t want him to huddle next to the bulldog with Laura, thinking passionately about letting him loose to kill people simply because they are Osage and therefore automatically dangerous. The Little House books promote a racist and white-centered understanding of westward expansion. They pit young readers against the people whose land was stolen by pioneers like Pa and his family.

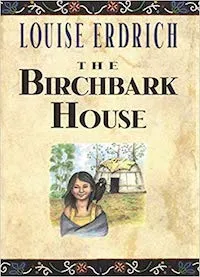

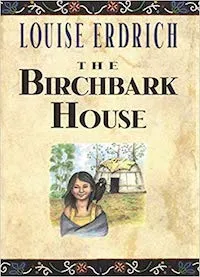

If my son chooses to read the books one day, I hope he’ll do so with a critical mind, considering himself an ally to those whose stories history textbooks have attempted to erase. For now, the two of us will sink into our favorite flowered reading chair and read Turtle Mountain Chippewa author Louise Erdrich’s answer to the Little House series: The Birchbark House. Together we will experience westward expansion from the perspective of the people who first lived, loved, and worked on the land we call home.

If my son chooses to read the books one day, I hope he’ll do so with a critical mind, considering himself an ally to those whose stories history textbooks have attempted to erase. For now, the two of us will sink into our favorite flowered reading chair and read Turtle Mountain Chippewa author Louise Erdrich’s answer to the Little House series: The Birchbark House. Together we will experience westward expansion from the perspective of the people who first lived, loved, and worked on the land we call home.

I ached to live in the olden days, in a humble cabin swallowed by prairie grasses. I wanted to churn butter and sweep earthen floors and strip to my petticoat and bloomers to cool off in a swimming hole. I vowed that I would pass this adoration for pioneer days along to my future children by reading them the Little House books from infancy.

I ached to live in the olden days, in a humble cabin swallowed by prairie grasses. I wanted to churn butter and sweep earthen floors and strip to my petticoat and bloomers to cool off in a swimming hole. I vowed that I would pass this adoration for pioneer days along to my future children by reading them the Little House books from infancy.

Through my freshman year of college, I reread the books in order each year. When Pioneer Girl came out in 2014, I devoured every annotation. In 2017, I burned through all 640 pages of Prairie Fires in three days—even with a toddler at home.

But these two books did more than fascinate me: they peeled away at the Laura I thought I’d grown up with, revealing someone more nuanced and controversial than I would have understood or admitted in childhood. In Pioneer Girl, for example, I learned that the first edition of Little House on the Prairie contained this line on the first page: “There the wild animals wandered and fed as though they were in a pasture that stretched much farther than a man could see, and there were no people. Only the Indians lived there” (Pioneer Girl p. 3n7). For seventeen years, no white reader noticed the cruelty of these words. When someone finally complained to Laura’s editor, she agreed to edit the racist lines, with the concession that “It was a stupid blunder of mine” (Pioneer Girl p. 3n7).

It was more than a blunder; it was harmful, certainly to any Indigenous person who might’ve read it, and to every non-Indigenous person who in those seventeen years formed early racist ideas. The lines speak to the anti-Indigenous sentiments that creep through Laura’s books, persisting even today. The first page of the current edition of Little House on the Prairie reads, “They were going to Indian country. Pa said there were too many people in the Big Woods now” (Ingalls Wilder p. 1). These lines aren’t so different from those Wilder edited out of the first edition: There are too many people in the Big Woods, yet Pa is illegally moving his family onto land very much populated by the Osage people. The racism of the line might be less glaring, but it’s there.

And it gets worse. In the Little House on the Prairie chapter “Indians in the House,” two Osage men appear on the trail leading to the Ingalls cabin. After comparing the men to snakes with “glittering eyes,” Laura starts “shivering; there was a queer feeling in her middle and the bones in her legs felt weak. She wanted to sit down” (Ingalls Wilder p. 135). Then, positive that the men are hurting Ma and Baby Carrie (when really they are only taking some food from a house illegally built on their land), Laura says, “I’m going to let [the bulldog] Jack loose…Jack will kill them” (Ingalls Wilder p. 136).

Upon hearing that Laura even thought about doing this, Pa is angry with her. Still, he says—as though seeing an Indigenous person is like spotting a grizzly bear in the wild—“So you’ve seen Indians at last, have you, Laura?” (143). In just one chapter, Laura strips Osage people of their humanity and plots to kill them.

Yes, I adored these books as a kid. I cherish the memories of reading and loving them for so long. I grew up with Laura Ingalls Wilder, but it’s time to distance myself from her because I know more now. (As do larger literary organizations like the ALSC.) I understand that while these aggressions may seem insignificant to some readers, they are brutal values that I don’t want my son to absorb. I don’t want him to huddle next to the bulldog with Laura, thinking passionately about letting him loose to kill people simply because they are Osage and therefore automatically dangerous. The Little House books promote a racist and white-centered understanding of westward expansion. They pit young readers against the people whose land was stolen by pioneers like Pa and his family.

Through my freshman year of college, I reread the books in order each year. When Pioneer Girl came out in 2014, I devoured every annotation. In 2017, I burned through all 640 pages of Prairie Fires in three days—even with a toddler at home.

But these two books did more than fascinate me: they peeled away at the Laura I thought I’d grown up with, revealing someone more nuanced and controversial than I would have understood or admitted in childhood. In Pioneer Girl, for example, I learned that the first edition of Little House on the Prairie contained this line on the first page: “There the wild animals wandered and fed as though they were in a pasture that stretched much farther than a man could see, and there were no people. Only the Indians lived there” (Pioneer Girl p. 3n7). For seventeen years, no white reader noticed the cruelty of these words. When someone finally complained to Laura’s editor, she agreed to edit the racist lines, with the concession that “It was a stupid blunder of mine” (Pioneer Girl p. 3n7).

It was more than a blunder; it was harmful, certainly to any Indigenous person who might’ve read it, and to every non-Indigenous person who in those seventeen years formed early racist ideas. The lines speak to the anti-Indigenous sentiments that creep through Laura’s books, persisting even today. The first page of the current edition of Little House on the Prairie reads, “They were going to Indian country. Pa said there were too many people in the Big Woods now” (Ingalls Wilder p. 1). These lines aren’t so different from those Wilder edited out of the first edition: There are too many people in the Big Woods, yet Pa is illegally moving his family onto land very much populated by the Osage people. The racism of the line might be less glaring, but it’s there.

And it gets worse. In the Little House on the Prairie chapter “Indians in the House,” two Osage men appear on the trail leading to the Ingalls cabin. After comparing the men to snakes with “glittering eyes,” Laura starts “shivering; there was a queer feeling in her middle and the bones in her legs felt weak. She wanted to sit down” (Ingalls Wilder p. 135). Then, positive that the men are hurting Ma and Baby Carrie (when really they are only taking some food from a house illegally built on their land), Laura says, “I’m going to let [the bulldog] Jack loose…Jack will kill them” (Ingalls Wilder p. 136).

Upon hearing that Laura even thought about doing this, Pa is angry with her. Still, he says—as though seeing an Indigenous person is like spotting a grizzly bear in the wild—“So you’ve seen Indians at last, have you, Laura?” (143). In just one chapter, Laura strips Osage people of their humanity and plots to kill them.

Yes, I adored these books as a kid. I cherish the memories of reading and loving them for so long. I grew up with Laura Ingalls Wilder, but it’s time to distance myself from her because I know more now. (As do larger literary organizations like the ALSC.) I understand that while these aggressions may seem insignificant to some readers, they are brutal values that I don’t want my son to absorb. I don’t want him to huddle next to the bulldog with Laura, thinking passionately about letting him loose to kill people simply because they are Osage and therefore automatically dangerous. The Little House books promote a racist and white-centered understanding of westward expansion. They pit young readers against the people whose land was stolen by pioneers like Pa and his family.

If my son chooses to read the books one day, I hope he’ll do so with a critical mind, considering himself an ally to those whose stories history textbooks have attempted to erase. For now, the two of us will sink into our favorite flowered reading chair and read Turtle Mountain Chippewa author Louise Erdrich’s answer to the Little House series: The Birchbark House. Together we will experience westward expansion from the perspective of the people who first lived, loved, and worked on the land we call home.

If my son chooses to read the books one day, I hope he’ll do so with a critical mind, considering himself an ally to those whose stories history textbooks have attempted to erase. For now, the two of us will sink into our favorite flowered reading chair and read Turtle Mountain Chippewa author Louise Erdrich’s answer to the Little House series: The Birchbark House. Together we will experience westward expansion from the perspective of the people who first lived, loved, and worked on the land we call home.