How I Discovered Alan Moore Without Knowing It

There’s many ways we encounter art that we fall in love with. Maybe a web-site recommends it to us, or maybe we stumble across it in a bookshop because it has a nifty cover. Maybe it wins an award. Maybe our friends recommend it. Increasingly, for me, it’s twitter. It’s astonishing how many books my friends on twitter wind up making me buy.

But there’s another interesting way we encounter art we eventually can’t live without, which is unconsciously, instinctively, with no real knowledge on our part. Our tastes and instincts can be so innate to who we are, we’re discovering art without realizing it. Of all the ways we can discover something, this is perhaps the strongest way we connect.

To explain what I’m talking about, I want to tell you about me and Alan Moore, whom I discovered long before I thought I did.

***

We moved an awful lot when I was a kid. My parents have worked in a range of roles for the Catholic Church since long before I was born, and that means a fair bit of moving. It’s rather like being an Army family, but with more churches and fewer people in camouflage.

I spent my formative years – the years when you’re still young, but have now become aware of the world and are being shaped and influenced by it – living on St. Croix, an island in the Caribbean. I was five years old or so. This is where the red thread begins.

I don’t know how I came to own it, but I owned this action figure. It had a name, and it was from a movie, but who cares what the packaging said? I was already making things up. He had a clumsy backstory, weird superpowers, and his name was “Monkey Man”

He went everywhere with me. In many ways, he was my best friend, the Hobbes to my Calvin. The island was a rough, occasionally bad place (it’s only a tropical paradise if you’ve got the money and you’re a visiting tourist). There were bars (on street corners) and bars (on house windows) and dangerous homeless people, occasional gunshots. There were breathtaking beaches and there was astonishing beauty, but what I’m saying is it was a rough place, I was lonely, and he was a friend, this Monkey Man.

It was an odd name. He wasn’t monkey-like in the slightest. He was neon yellow. All of his joints had long strings in them so he could collapse and “disguise himself as a pile of logs!” (neon yellow logs, mind. Even as a small child, I thought this was dodgy). Weird and bumpy, his head sloped into his body, he had deep-set red eyes…

He was Swamp Thing, in fact.

I had a number of them. Various Swamp Thing action figures. They existed, I now know, because an appallingly bad Swamp thing movie had just come out. They were all brilliant, those action figures, but the neon yellow one, he was Monkey Man and he was special. Who can explain why kids latch onto the things they do?

Suffice it to say, a toy held together by string was not destined for a long life in tropical island humidity and also the hands and schemes of an imaginative little boy. He disintegrated and was replaced more than once. I never knew how. There were no toy shops on the island to speak of, and this was well before the internet.

It would be an awfully long time before I had any real idea of what Swamp Thing was, let alone the name of the person who had ultimately defined him.

***

The red thread carries on, further into my childhood. Now I am eight or nine, we are living in a small northern Minnesota town. Monkey Man is a long distant memory, but action figures are not. My storytelling and imagination has also progressed. All the plethora of action figures I own have complex names and backstories and interactions with each other (never mind that four of the action figures are just different-style Batmans). Star Trek and Star Wars have gobbled up my life, and also there are a lot of comic books.

I read a lot of comics. Mostly out of order, and with no idea who wrote or drew them. They were super-hero comics and mostly, they floated in one ear and out the other. The odd stories have stuck with me (why was Captain America turning into a werewolf? Why is the Hulk calm and fully clothed and in a lab coat? Why is this guy sometimes Iron Man and sometimes War Machine?)

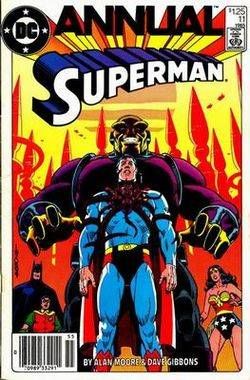

One really stuck with me, though. It was bothersome, in some way my young brain couldn’t work out, and long after reading it, I would think about it and pick at it in my mind. It was a Superman comic. In it, a villain named Mongul puts Superman in a catatonic state with a strange alien parasite attached to his chest. Superman dreams a lifetime in the space of a few hours, and when the parasite goes, that life of happiness is ripped away from him. This was Superman Annual #11, and the story was called “For The Man Who Has Everything.”

One really stuck with me, though. It was bothersome, in some way my young brain couldn’t work out, and long after reading it, I would think about it and pick at it in my mind. It was a Superman comic. In it, a villain named Mongul puts Superman in a catatonic state with a strange alien parasite attached to his chest. Superman dreams a lifetime in the space of a few hours, and when the parasite goes, that life of happiness is ripped away from him. This was Superman Annual #11, and the story was called “For The Man Who Has Everything.”

It was bothersome in a way no other superhero comic had been for me. It worried me, the sense of lives lost and the permeated atmosphere of sorrow. It bothered me the way the Twilight Zone episode Time Enough to Last had done, the way the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode The Inner Light had, the way a novel I read at the same time called Bridge to Terabithia would do. It stuck with me because there were two great fault lines rubbing against each other in that comic – one, the superficial and silly world of men in capes, the other the deep thoughts of life and loss and tragedy – and those fault lines were causing earthquakes.

Here, though, the matter ends much as it did with Swamp Thing: I had encountered something which made a lasting impression on me, but had no idea what it was or why it mattered, or who had done it to me. I was too young to really analyze the things that struck me like a tuning fork.

***

The years went by. I grew up, got jobs, got debt, got married, got children, got life. Somewhere in there, I discovered Alan Moore properly, knew who he was by name. I discovered him through Neil Gaiman (whom I discovered through another long red thread, but never mind). Discovering Alan Moore properly was exciting. There is a tremendous excitement when you encounter an author and know right away that you two are made for each other. It’s like opening a treasure chest.

So I discovered Watchmen, Alan Moore’s astonishing landmark work about not only superheroes, but life, death, honor, nuclear apocalypse, the 1980s, and much more. It was the work that broke the superhero genre (a blow to the kneecaps from which I do not think it’s ever recovered). I discovered V for Vendetta. I discovered Promethea, Lost Girls, Supreme, Swamp Thing, Big Numbers (what fragments of it exist), A Small Killing, and I could just go on and on.

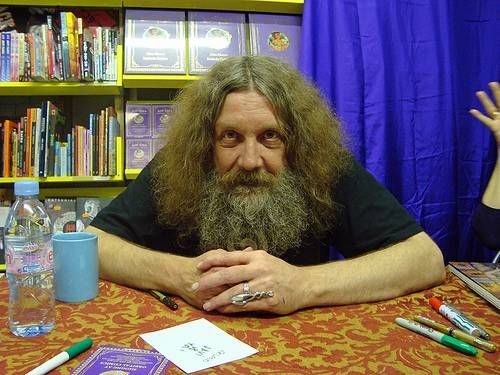

I discovered his ideas and interviews and opinions. When Alan Moore gives an interview, you can bet good money it won’t run under ten thousand words. He doesn’t answer, he holds forth on topics…and it would be awful, if he weren’t funny, erudite, and brilliant about it. Never pompous, always interesting. Reading his interviews did as much for me as his fiction did: they clarified a lot of my own puzzling views about politics, art, the mind, work ethics, and so on.

If I have to patron saints in my life, then he is one, sitting on my shoulder and casting a shadow somewhere across everything I write. But amid the delight of discovering this amazing author, I also begin looking back through my life, and that’s when I finally spot the long red thread, winding its way back through my childhood.

This isn’t at all very epic stuff, because we’re actually talking the cliche building blocks of a romantic comedy here. We’re discussing the final moments of the film, when the guy or the girl turns up at the other person’s door and tearfully says something like “It was you all along, wasn’t it?” And then they kiss and credits roll. In romantic comedies, it’s pretty inevitable who on the screen is going to get together. It’s destiny (manifesting itself on this plane of existence as “a lazy screenwriter”). It’s the same thing with readers and authors, although there isn’t a kissing scene quite as often.

Alan Moore became a huge force in my life. And then I looked back and discovered that, actually, he had been all along.

***

A few years ago, for my birthday, my mom got me a little statue. I laughed when I opened it, and they did too. I don’t know if it was meant to be a silly present, a bit of an affectionate joke or not, but it doesn’t matter.

It’s about six inches tall, and it is a highly-detailed statue of Swamp Thing, his fists made of bundles of roses, modeled in amazing detail off of a Michael Zulli painting, used as a cover on one volume of Swamp Thing.

For my mother, it was a statue of my childhood toy, my imaginary friend, Monkey-Man and she laughed about that, and gave me the statue. But for me it’s a statue of an amazing character named Swamp Thing…and it’s a little reminder of this long red thread winding all the way back through my life and into childhood. And it’s a little totemic figure for this author who has made, and continues to make, a tremendous impact on my life and work. And it’s a reminder of my childhood imagination, made manifest in a little non-ape figure who will forever be Monkey-Man on some level.

This, then, is my red thread. If you live and love, read and dream and imagine, then doubtless you have your own red threads running up and down your lifespan, perhaps dozens of them, entangling you but never tying you down.

Aren’t they terrific?