Save My Place! A Brief Look at the History of Bookmarks

Whether you use a sticky note, an old receipt, or something less conventional, you’re sure to be familiar with the general function and shape of a bookmark. Librarians from all over have reportedly found boarding passes, personal letters, money, or even fake eyelashes tucked in between the pages of returned books. An article titled “School Libraries” by J.H. Lumby in The Librarian and Book World published in 1921 reported finding “a piece of bread and jam” in a book returned to a local public library, proving that the weird and wonky placeholders of today aren’t as modern as we might think.

It makes sense, the impulse to save your place so you don’t spend the first five minutes you sit down to read trying to pick up where you left off. But how much have bookmarks changed since their invention?

Bookmarkers: A Useful but Humble Accessory

While bookmarks may have been around since the introduction of the codex, it’s difficult to pinpoint an exact invention date. Volume 22 of Colorado Libraries, published in 1996, recounts a line from Confessions by St. Augustine from around 400 AD in which he writes, “Having inserted my finger, or some other mark, I closed the book and…told it all to Alypius.” Thus shows the use, or at least the need, of some kind of “mark” for saving his place while reading.

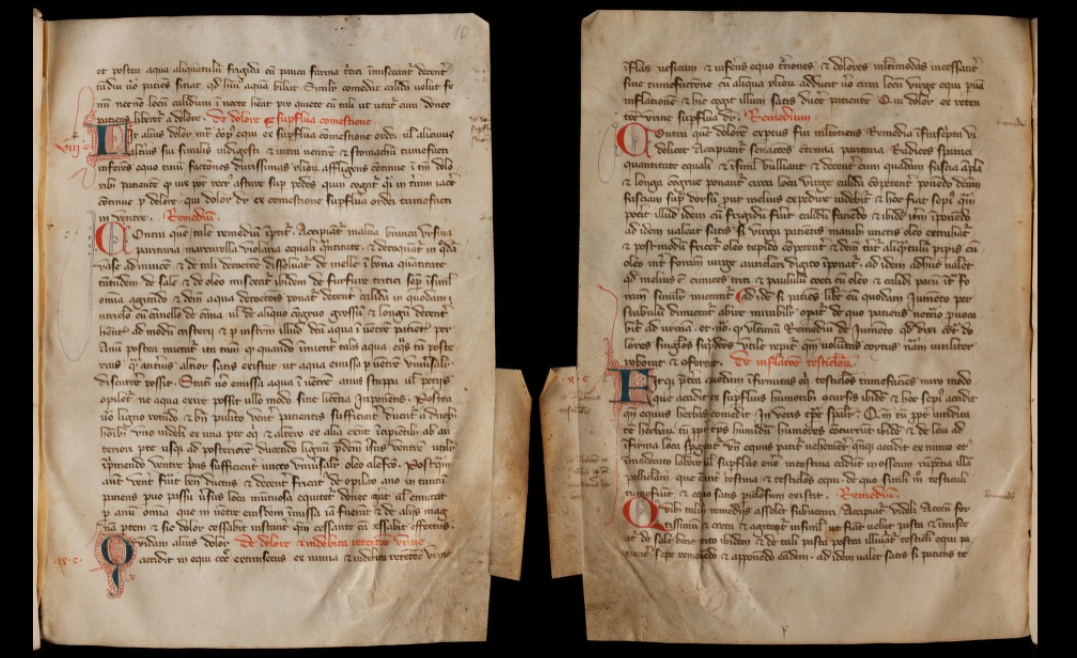

The earliest currently known bookmark is from the 6th century AD, a leather bookmark attached to the cover of a codex found in the remains of a monastery in Egypt in 1925.

According to the 1907 book, The History of Development of the Bookmarker by Frank Hamel, the “general style and shape” of bookmakers, what bookmarks were called in history, haven’t changed much. Also called a register or a “registrum corula” in the Middle Ages, bookmarks at the time held quite a bit more weight than the tossed-in pieces of paper that often come with a book purchase in the modern day.

Hamel argues as the practice of including page numbers in books hadn’t yet come into practice (and wouldn’t until the late 16th century), some readers had difficulty keeping track of their place in the various treatises and books of the 1400s and 1500s. As such, the bookmarkers were born, though slightly different than how we see them today.

In the 15th century, bookmarks were “narrow strips of parchment or vellum” attached to leaves in a book so they stood out from the edges like tabs.

These types of bookmarks generally indicated different sections or articles as they were immovable and could help readers orient themselves through different portions of the book rather than marking where they had stopped reading before.

Another type developed in the 15th century is still around today. They were strips of silk ribbon or cord attached to the binding of the book that could be moved between pages. You’ve probably seen this type in the fancier books at the bookstore or ones you’ve received as a gift.

Hamel writes, “much variety is found in the style of the silken markers”: some with tassels, woven balls, or even embroidered ornaments. Many featured religious images, greetings, or other designs through embroidery or hand painting.

One of the earliest references to bookmarks, according to Densky-Wolff, was when Queen Elizabeth I was given a silk bookmark inserted in the binding of a book made by her printer, Christopher Barker.

A “trade lounger” in The American Stationer published in 1887 reported a silk manufacturer created a “line of bookmarks” with portraits, notably one of Pope Leo XII with “Pope Leo XIII, December 31st, 1837 – 1887.”

In The Book Lover vol. 1, published in 1888, a section titled “Ben: Bookman’s Budget discusses a bookmark’s impact on a book. The author writes, “the term ‘register’ is the binder’s name for a bookmark” which consist of “very thin and narrow ribbons of silk, one end of which is fastened at the head-band in the processes of binding, they can do the book no possible harm and can never be lost.”

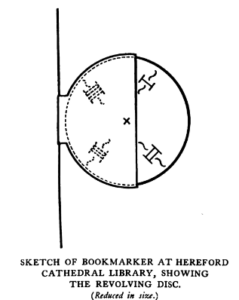

Another type of marker with a rotating disc attached helped individuals indicate not only the page but also the column they’d stopped reading at so they could pick back up with ease when they returned to the book.

Then came the “loose bookmarker,” much in the vein of the ones we’re familiar with today. According to Hamel, as the world “flooded with books,” the importance of the bookmark was reduced as “readers were less careful” and turned to other means like dog-earing or using “strips of common paper.” These detached-style bookmarks grew in popularity in the mid-1800s.

Advertising and Informing

In later years, bookmarks became ways for different groups to advertise their wares or share information.

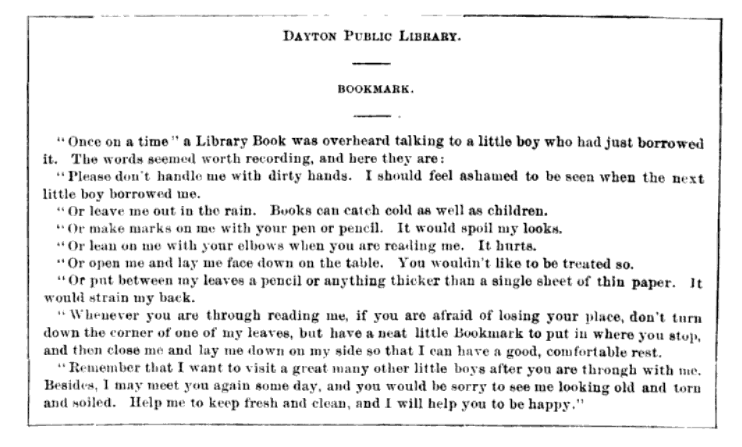

The libraries of Milwaukee, Cleveland, Dayton, and other cities created a “children’s bookmark,” which was recreated in the “Annual Report of the Commissioner of Education” volume 1, published in 1899, with the following story upon it to encourage children to handle books with care and use only bookmarks to keep their place:

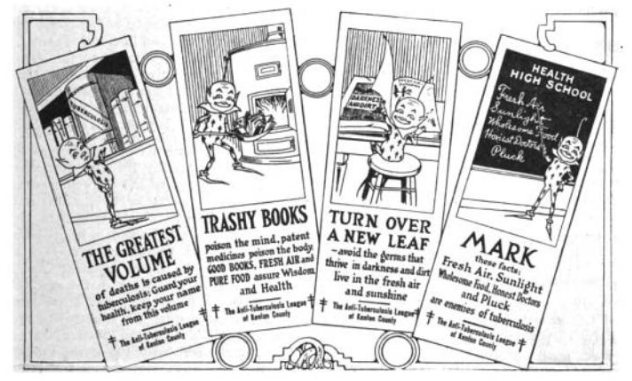

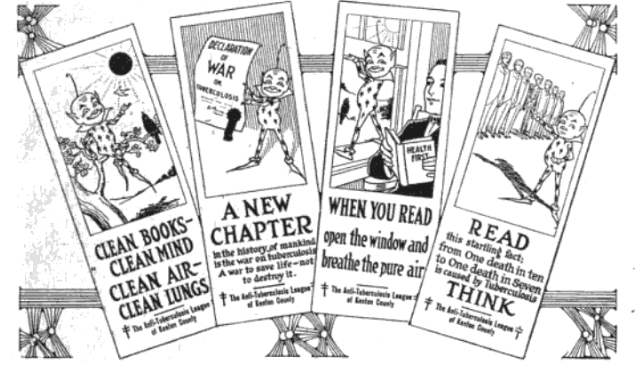

The Bulletin of The National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, published in May of 1915, reported on an idea created by a volunteer with the Anti-Tuberculosis League of Kenton Co. The volunteer devised eight bookmarks to be given to public libraries with information about how to avoid catching tuberculosis with sayings like “clean books — clean mind, clean air — clean lungs” or “when you read open the window and breathe the pure air” or more morbidly “Read this startling fact: from one death in ten to one death in seven is caused by tuberculosis.”

Another informational attempt at bookmarks was by the Commercial Club, who printed bookmarks of “an educational nature regarding the manufacturing industries of Kansas City” in 1914. They produced two bookmarks, one saying, “Kansas City Has Eleven Hundred and Sixty-Seven Factories” and the other saying, “Kansas City Stands Tenth Among the Cities of the United States in Total Values of Manufactured Products.”

“Druggists” or pharmacists also took to using bookmarks to advertise, according to the American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record from 1911. Frederick F Ingram Company created bookmarks containing their name and an advertisement for Milkweed Cream and other Ingram specialties. “Soap makers, perfumeries, insurance companies, and food and furniture manufacturers” also produced sets of bookmarks to give away or as rewards for purchasing their products.

As you can see, the bookmark hasn’t changed all that much since its invention, though perhaps the modern day sees a much wider range of style, shape, and affordability than those of the past. If you’re interested in picking up a bookmark or two for yourself, check out these 11 bookmarks for all genres or these 15 origami bookmarks!