What’s in a Blurb?: The History of Book Blurbing

It’s cliche, but books are judged by their covers. For one thing, often the cover lets the reader know what kind of book they are buying. White woman in a gown or a shirtless muscle-bound man: romance. Bright cartoon picture superimposed with san serif: young adult. Dark with silhouetted figure in the mist: mystery. Dripping font titles: probably horror. So, let’s say you’re a genre reader, have found your section in the bookstore, and are trying to find something new. The next thing to examine are the blurbs. If Neil Gaiman stans see he’s read and endorsed a book, they will be more likely to give it a try. Haruki Murakami says this book is a must read? Then read you must.

Blurbs are meant to catch a buyer’s eye and encourage them to try something new, maybe a debut author they’ve never heard of, because this name they trust says it is worth their time. Hundreds of thousands of books are published each year. New authors, all authors for that matter, are trying to do what they can to stand out. A quote from Oprah or a Reese’s Book Club sticker can go a long way.

Where Do Blurbs Come From?

The term “blurb” was coined by humorist Gelett Burgess on the cover of his 1906 book Are You a Bromide? He defined blurb as “a flamboyant advertisement” or “an inspired testimonial.” On the cover, Miss Belinda Blurb is featured touting, “This book is the proud purple penultimate!!” While Mr. Burgess came up with the word, the earliest usage was years before.

Walt Whitman, American author, has the first known blurb on the second printing of his now famous Leaves of Grass. Then little known Whitman sent a copy of Leaves of Grass to Ralph Waldo Emerson after its first printing. Emerson wrote back a letter of praise encouraging Whitman in his writing. At the time, Emerson was prolific in America and his opinion was valued. Whitman, being a keen marketer, had Emerson’s letter to him published in the New York Tribune in 1855, a few months after receiving it.

One line in particular was singled out: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.” Leaves of Grass, now going into its second printing in 1856, had that line from Emerson’s letter written in gold on the spine of the book alongside the title and author’s name. It should surprise no one that Whitman was adept at self-promotion. This was the man who years later would publish a work titled Song of Myself.

What Do Professionals Think of Book Blurbs?

Publishing quickly caught on and began blurbing books regularly. It didn’t take long for the opinion of book blurbs to turn, however. In 1936, George Orwell in his essay “In Defense of the Novel” described blurbs as “disgusting tripe” and that “novels are being shot at you at the rate of fifteen a day and every one of them an unforgettable masterpiece which you imperil your soul by missing.” Blurbs continue to plague writers today as well. Author Jeanette Winsterson went so far as to set her own books on fire because she didn’t like the “cozy little domestic blurbs” on the newest cover of her work The PowerBook.

Some authors won’t go so far as to burn their bad blurbs or call them disgusting, but they can be more of a hassle than they’re worth. Pulitzer-winning novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen made his frustration about blurbs clear to the Wall Street Journal, “They create so much work, emotional labor and guilt, whether one is writing one or one is asking for one.” Often authors solicit other writers they don’t know in hopes of getting a blurb from someone established in their field. I imagine it must feel like going up to a stranger at a work party and saying, “Hey, I need a favor.”

Eric Smith, literary agent and author of Don’t Read the Comments, agrees that the process isn’t the best. “Are they a pain to get? Sure. It’s awkward sometimes, but that’s what your agent and editor are for.”

Who Are Book Blurbs For?

That leads to the question of who are blurbs really for?

Sometimes blurbs can be for the authors themselves. In an opinion piece for The New York Times, Sophfronia Scott said she half heartedly sent out queries she thought were longshots for her book, All I Need to Get By, and got back a glowing review from Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., the the director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard University. “In one blurb he had spoken to my innermost hopes and dreams of wanting to write at the level of a Toni Morrison, and he told me it was possible.” Dr. Gates’s blurb changed her life and gave her confidence to continue in her craft.

While what happened to Scott might be the exception to the rule, most authors I spoke to agree on blurbs usefulness. Andie J. Christopher, romance author of Not the Girl You Marry, Not that Kind of Guy, and forthcoming Hot Under His Collar, says, “at their best, they allow authors to point their readers towards other writers who might resonate with them. In romance, where readers are voracious, that can be a useful tool.”

Zoraida Cordova, a YA author and author of forthcoming The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina, a work of fiction for adults, thinks they are useful both with readers and professionally. When readers “see that their favorite author has given a proverbial thumbs up to a book and perhaps might want to take a chance on it” they are more likely to spend money based on that endorsement. More than that, blurbs can show “that colleagues are saying nice things about your book and you have that type of community support.” Who you know and who knows you can lend your work certain privileges. If a well established author who has worked with a certain publisher for years recommends you, then that publisher might be more willing to take a chance with your manuscript. Same for literary agents and other industry professionals.

So many potential benefits of blurbs! The more the better, right? When the blurbs are too numerous for the cover, they might continue on the first few pages of the book. Whitman could not have anticipated such blurbery. We’ve all picked up books that have pages and pages of accolades. As a reader, sometimes I think, “Sheesh I picked up the book already, you don’t have to spend the first three pages convincing me. Your writing should convince me to stay.”

Eric Smith says this is a common trap for writers and that they shouldn’t lose sight of the real audience. “I feel like authors sometimes get hung up on trying to have as many as possible, or industry folks stress about getting them before even pitching a book to publishers…when blurbs are simply for readers, booksellers, and librarians.” He goes on to describe blurbs as “easy entry points” for people looking for something new and different. This is the crux of the blurb.

Where Are Blurbs Going?

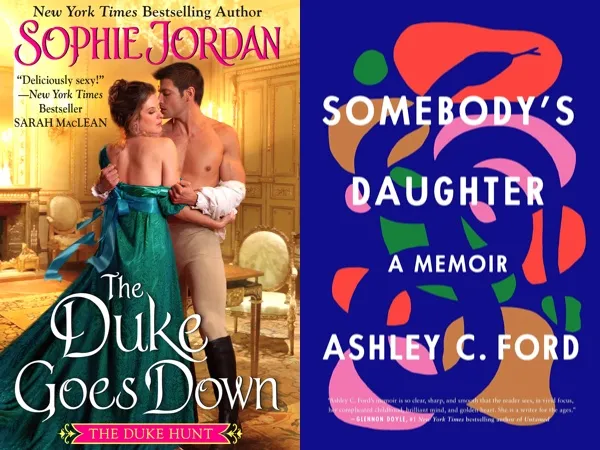

Today, the most effective blurbs aren’t that much different from Walt Whitman’s. A short endorsement from a trusted author that readers should take a chance on this newbie. Sarah MacLean’s blurb for Sophie Jordan’s The Duke Goes Down is an excellent example with the blurb in the top left corner. Glennon Doyle’s blurb on the bottom front cover of Ashley C. Ford’s new memoir, Somebody’s Daughter, is a little longer, but the idea and aesthetic are the same.

All this effort and thought and communication time. Are blurbs actually helping to sell books? The data is unclear. According to research from NPR, blurbs are one factor among many as finite data is difficult to obtain. It’s hard to ascertain if it was the cover or the blurb that first caught the buyer’s eye.

Ambiguous data doesn’t seem to factor into blurbs’ future. All signs point to them sticking around. Many established writers enjoy paying it forward by blurbing debut authors. Stephen King and Zadie Smith are both known for blurbing first time authors. Publishers and literary agents think they are worth the time and effort because blurbs keep appearing on books. Just like with any part of a job, there are aspects some people hate that others enjoy, and whether blurbs are a placebo or not doesn’t seem to matter. Just because something is a placebo doesn’t mean the placebo effect isn’t real, proven science. The blurb effect is here to stay.