The Appeal of Graphic Novels about Anthropomorphized Animals

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

There’s a long and proud tradition of turning non-human animals and hybrid animals into characters of graphic novels and comics. After all, the single most lauded graphic narrative of all time, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, depicts cats, mice, and pigs. This is partly for necessary distance, given the very emotional subject matter of the Holocaust and Spiegelman’s relationship with his survivor father.

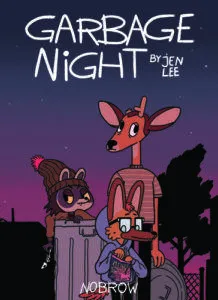

Other comics creators have also used the seemingly childlike to illuminate the serious, when it comes to human-like animals. Jen Lee’s Garbage Night, for instance, develops a striking visual language. Its main characters are young runaways who vaguely resemble a deer, a raccoon, and other species.

Graphic novelists also use human-like characters to find humor in the disconnect between animal bodies and human behaviors. Diane Obomsawin’s On Loving Women, which collects anecdotes about queer women’s experiences both big and small, mines this incongruity. For instance, “there was a girl in my sister’s class who had a horse face,” says a deerlike creature of a horselike creature. The protagonist realizes this attraction stems from her love of Wonder Woman, whose body and face are horselike (in a good way).

Other comics creators have also used the seemingly childlike to illuminate the serious, when it comes to human-like animals. Jen Lee’s Garbage Night, for instance, develops a striking visual language. Its main characters are young runaways who vaguely resemble a deer, a raccoon, and other species.

Graphic novelists also use human-like characters to find humor in the disconnect between animal bodies and human behaviors. Diane Obomsawin’s On Loving Women, which collects anecdotes about queer women’s experiences both big and small, mines this incongruity. For instance, “there was a girl in my sister’s class who had a horse face,” says a deerlike creature of a horselike creature. The protagonist realizes this attraction stems from her love of Wonder Woman, whose body and face are horselike (in a good way).

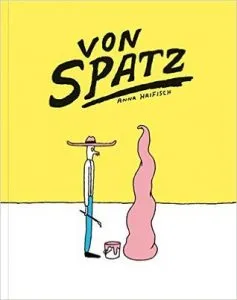

The humor is more absurdist in the work of Jason, whose tall, mournful-looking characters typically sport paws or rabbit ears. Anna Haifisch’s Von Spatz has a similar kind of bleak off-kilter humor. Animal-ish characters populate this eccentric story of creative anxiety. This is appropriate enough for a tale about Walt Disney, whose creative life focused on iconic, very stylized animals. One Von Spatz character complains about a fellow airplane passenger eating like a crocodile. That man is in fact a crocodile.

Giving animals human traits is also a way to freshen familiar ideas. Noir tropes seem more amusing when the detective is a hard-boiled cat rather than a hard-boiled human, as in the Blacksad series by Juan Díaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido. And the main character of B. Mure’s Ismyre, a lonely sculptor, might feel like an overly familiar isolated creative type, were he not a feline. The mouse painter in Kickliy’s delightful Musnet books allows for another unusual take on creative impulses and hardships.

The humor is more absurdist in the work of Jason, whose tall, mournful-looking characters typically sport paws or rabbit ears. Anna Haifisch’s Von Spatz has a similar kind of bleak off-kilter humor. Animal-ish characters populate this eccentric story of creative anxiety. This is appropriate enough for a tale about Walt Disney, whose creative life focused on iconic, very stylized animals. One Von Spatz character complains about a fellow airplane passenger eating like a crocodile. That man is in fact a crocodile.

Giving animals human traits is also a way to freshen familiar ideas. Noir tropes seem more amusing when the detective is a hard-boiled cat rather than a hard-boiled human, as in the Blacksad series by Juan Díaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido. And the main character of B. Mure’s Ismyre, a lonely sculptor, might feel like an overly familiar isolated creative type, were he not a feline. The mouse painter in Kickliy’s delightful Musnet books allows for another unusual take on creative impulses and hardships.

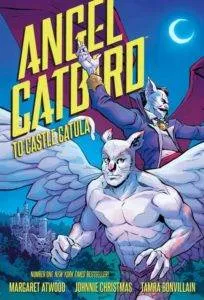

But perhaps this is overthinking. Drawing animals with human characteristics is of course a great opportunity for a lot of animal puns. Angel Catbird, by Margaret Atwood, Johnnie Christmas, and Tamra Bonvillain, delights in the wordplay. The love interest is Cate Leone, whose hangout is the Catastrophe Club, where she’s spied on by the rat minion Ratilda, etc.

It’s also a chance to comment on human arrogance and responsibility in seeking to dominate the natural world. Rover Red Charlie, by Garth Ennis and Michael Dipascale, imagines an apocalyptic world where domestic dogs feel bereft and disoriented. Do they seek out humans, whom they can no longer trust? Can they construct a civilization less damaging than one created by homo sapiens?

All this is only a brief look; anthropomorphized animals have many other functions in comics. It’s clear that this way of representing characters won’t die out anytime soon.

More reading:

“My Kryptonite: Anthropomorphic Animals”

“Read Harder: Anthropomorphic Animals (for Paul)”

But perhaps this is overthinking. Drawing animals with human characteristics is of course a great opportunity for a lot of animal puns. Angel Catbird, by Margaret Atwood, Johnnie Christmas, and Tamra Bonvillain, delights in the wordplay. The love interest is Cate Leone, whose hangout is the Catastrophe Club, where she’s spied on by the rat minion Ratilda, etc.

It’s also a chance to comment on human arrogance and responsibility in seeking to dominate the natural world. Rover Red Charlie, by Garth Ennis and Michael Dipascale, imagines an apocalyptic world where domestic dogs feel bereft and disoriented. Do they seek out humans, whom they can no longer trust? Can they construct a civilization less damaging than one created by homo sapiens?

All this is only a brief look; anthropomorphized animals have many other functions in comics. It’s clear that this way of representing characters won’t die out anytime soon.

More reading:

“My Kryptonite: Anthropomorphic Animals”

“Read Harder: Anthropomorphic Animals (for Paul)”

Other comics creators have also used the seemingly childlike to illuminate the serious, when it comes to human-like animals. Jen Lee’s Garbage Night, for instance, develops a striking visual language. Its main characters are young runaways who vaguely resemble a deer, a raccoon, and other species.

Graphic novelists also use human-like characters to find humor in the disconnect between animal bodies and human behaviors. Diane Obomsawin’s On Loving Women, which collects anecdotes about queer women’s experiences both big and small, mines this incongruity. For instance, “there was a girl in my sister’s class who had a horse face,” says a deerlike creature of a horselike creature. The protagonist realizes this attraction stems from her love of Wonder Woman, whose body and face are horselike (in a good way).

Other comics creators have also used the seemingly childlike to illuminate the serious, when it comes to human-like animals. Jen Lee’s Garbage Night, for instance, develops a striking visual language. Its main characters are young runaways who vaguely resemble a deer, a raccoon, and other species.

Graphic novelists also use human-like characters to find humor in the disconnect between animal bodies and human behaviors. Diane Obomsawin’s On Loving Women, which collects anecdotes about queer women’s experiences both big and small, mines this incongruity. For instance, “there was a girl in my sister’s class who had a horse face,” says a deerlike creature of a horselike creature. The protagonist realizes this attraction stems from her love of Wonder Woman, whose body and face are horselike (in a good way).

The humor is more absurdist in the work of Jason, whose tall, mournful-looking characters typically sport paws or rabbit ears. Anna Haifisch’s Von Spatz has a similar kind of bleak off-kilter humor. Animal-ish characters populate this eccentric story of creative anxiety. This is appropriate enough for a tale about Walt Disney, whose creative life focused on iconic, very stylized animals. One Von Spatz character complains about a fellow airplane passenger eating like a crocodile. That man is in fact a crocodile.

Giving animals human traits is also a way to freshen familiar ideas. Noir tropes seem more amusing when the detective is a hard-boiled cat rather than a hard-boiled human, as in the Blacksad series by Juan Díaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido. And the main character of B. Mure’s Ismyre, a lonely sculptor, might feel like an overly familiar isolated creative type, were he not a feline. The mouse painter in Kickliy’s delightful Musnet books allows for another unusual take on creative impulses and hardships.

The humor is more absurdist in the work of Jason, whose tall, mournful-looking characters typically sport paws or rabbit ears. Anna Haifisch’s Von Spatz has a similar kind of bleak off-kilter humor. Animal-ish characters populate this eccentric story of creative anxiety. This is appropriate enough for a tale about Walt Disney, whose creative life focused on iconic, very stylized animals. One Von Spatz character complains about a fellow airplane passenger eating like a crocodile. That man is in fact a crocodile.

Giving animals human traits is also a way to freshen familiar ideas. Noir tropes seem more amusing when the detective is a hard-boiled cat rather than a hard-boiled human, as in the Blacksad series by Juan Díaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido. And the main character of B. Mure’s Ismyre, a lonely sculptor, might feel like an overly familiar isolated creative type, were he not a feline. The mouse painter in Kickliy’s delightful Musnet books allows for another unusual take on creative impulses and hardships.

But perhaps this is overthinking. Drawing animals with human characteristics is of course a great opportunity for a lot of animal puns. Angel Catbird, by Margaret Atwood, Johnnie Christmas, and Tamra Bonvillain, delights in the wordplay. The love interest is Cate Leone, whose hangout is the Catastrophe Club, where she’s spied on by the rat minion Ratilda, etc.

It’s also a chance to comment on human arrogance and responsibility in seeking to dominate the natural world. Rover Red Charlie, by Garth Ennis and Michael Dipascale, imagines an apocalyptic world where domestic dogs feel bereft and disoriented. Do they seek out humans, whom they can no longer trust? Can they construct a civilization less damaging than one created by homo sapiens?

All this is only a brief look; anthropomorphized animals have many other functions in comics. It’s clear that this way of representing characters won’t die out anytime soon.

More reading:

“My Kryptonite: Anthropomorphic Animals”

“Read Harder: Anthropomorphic Animals (for Paul)”

But perhaps this is overthinking. Drawing animals with human characteristics is of course a great opportunity for a lot of animal puns. Angel Catbird, by Margaret Atwood, Johnnie Christmas, and Tamra Bonvillain, delights in the wordplay. The love interest is Cate Leone, whose hangout is the Catastrophe Club, where she’s spied on by the rat minion Ratilda, etc.

It’s also a chance to comment on human arrogance and responsibility in seeking to dominate the natural world. Rover Red Charlie, by Garth Ennis and Michael Dipascale, imagines an apocalyptic world where domestic dogs feel bereft and disoriented. Do they seek out humans, whom they can no longer trust? Can they construct a civilization less damaging than one created by homo sapiens?

All this is only a brief look; anthropomorphized animals have many other functions in comics. It’s clear that this way of representing characters won’t die out anytime soon.

More reading:

“My Kryptonite: Anthropomorphic Animals”

“Read Harder: Anthropomorphic Animals (for Paul)”