SOME GIRLS ARE Removed from Summer Reading List in South Carolina

“…an unflinching look at the intricacies of high school relationships and how easily someone’s existence can change. Fans of the film Mean Girl[s] will enjoy this tale of redemption and forgiveness.” —School Library Journal, starred review

“…it’s Regina’s lack of recourse that makes this very real story all the more frightening and effective. Regina’s every emotion is palpable, and it’s impossible not to feel every punch—physical or emotional—she takes.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Blackmail, fighting and retaliation all come center stage, and Regina sees that despite her best efforts, a truly mean girl is not easily knocked down. Powerful and compelling.” —Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“I’m not a prude for God’s sake and I understand that these are issues kids are facing – the drugs, the alcohol, the bullying – but there has to be a way to present it that’s not destructive to them. I get they’re trying to find something the kids are interested in, but this book is trash.” —Melanie MacDonald, West Ashley High School parent

Incoming freshman enrolled in Honors English 1 had a choice between two books for their summer reading this year: Rikers High by Paul Volponi, and Some Girls Are by Courtney Summers. Rikers High is the story of one boy’s experience in a juvenile detention facility; Some Girls Are is about a girl who goes from bully to bullied after she’s sexually assaulted by her best friend’s boyfriend.

Incoming freshman enrolled in Honors English 1 had a choice between two books for their summer reading this year: Rikers High by Paul Volponi, and Some Girls Are by Courtney Summers. Rikers High is the story of one boy’s experience in a juvenile detention facility; Some Girls Are is about a girl who goes from bully to bullied after she’s sexually assaulted by her best friend’s boyfriend.

According to this article at The Post and Courier, after reading the first 74 pages of Some Girls Are, parent Melanie MacDonald called the school to complain.

The school responded by adding a third option to the reading list: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, by Betty Smith.

But it seems that a third option wasn’t what MacDonald was looking for—what she was looking for was for the book to be removed from the list, period. She filed a complaint with the district, but before the challenge committee met, West Ashley’s principal and the English department removed the book from the list.

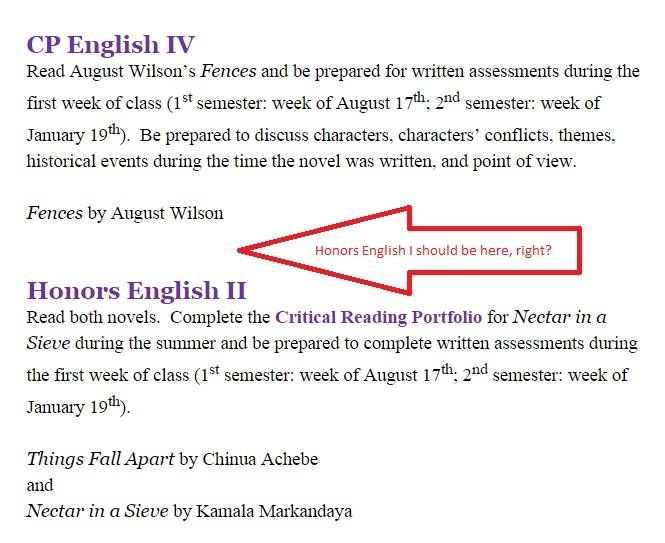

According, again, to the article at The Post and Courier, it has been replaced with Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak—and I have to admit, I’m totally flabbergasted that the school is replacing a challenged title with Speak, which gets challenged, like, every fifteen minutes… seriously, are they trolling?—though at this time, the school’s website doesn’t reflect that change:

I’m all for parents being involved in their childrens’ lives.

I’m all for parents being involved in their childrens’ schooling.

And, as much as I like to see kids pick up and read whatever the heck book they want, I’m all for MacDonald asking for another book for her daughter. I suspect our opinions about how to keep children safe—through information versus through shielding—might differ, but that’s none of my business.

Where she’s overstepped is in assuming that because the book is wrong for her and for her daughter, that it’s wrong for all of the other students enrolled in that class. Where she’s overstepped is in making that decision for all of those other families, for all of those other students.

Where the school has failed its students is in changing an assignment without going through a formal review process in order to appease one vocal parent. Even beyond setting a terrible precedent, it sends a terrible message to the students who’ve already read the book and who’ve connected with it—teens who’ve seen themselves, heard themselves in it. By capitulating to the demands of one worldview, they’re telling those students that their voices don’t deserve to be heard, that their stories aren’t worthy of telling. That they should keep their heads bowed, their hands folded, their mouths shut.

Books like Some Girls Are—and yes, Speak—tell the truth. The truths that they tell aren’t easy truths, and they aren’t comfortable truths, but they’re truths nonetheless. Books like Some Girls Are—and yes, again, Speak—are lifesaving books. But Courtney Summers has already said all this, and better than I ever will:

One of the reasons I write my novels is to validate the experiences many teens go through in their day-to-day lives. My readers expect me to be honest in my work and, as a result, I’m humbled by the emails I receive from them thanking me for reflecting their truth in the pages of my books.

Some Girls Are is not smut. Some Girls Are is not trash. It’s not a problem when someone chooses not to read any of my books, whatever their reasons, but it is problematic when that choice has been taken away from those who might feel differently.

I’ll be re-reading Some Girls Are this weekend, and I’ll be tweeting about it at #SomeGirlsAre. I’d love it if you’d join me.