A Look Inside Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Dolly Parton knows how to stay in the news. The biggest splash she made lately was voicing her desire to recreate her 1978 Playboy cover for her 75th birthday. That Playboy cover also showed up in the recent Dolly Parton Challenge. She started that meme by posting a grid of appropriate photos for LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, and Tinder. Before that, there were stories exploring her controversial decision to take the word “Dixie” out of her Stampede dinner show, that unholy marriage of Medieval Times and a Civil War reenactment.

These are the kinds of stories that make national news. If you follow the Dolly news ticker, however, you’ll notice a steady stream of smaller stories from local outlets. They’re often service journalism pieces letting area residents know that local kids can now benefit from Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library, the program that sends free books to children from birth to age five.

You might have seen Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library in the news in 2018 when the program donated its 100,000,000th book. Yes, that’s one hundred million. The Imagination Library has declared itself the largest literacy program in the world. It seems simultaneously impossible to prove and tough to refute, tossing numbers that big around. I first learned of the Imagination Library around ten years ago. A friend mentioned offhandedly that Dolly sent her child a free book every month. I was baffled, never having thought of Dolly as a champion of literacy, or as she puts it in her folksy parlance, a “book lady.” Learning that Dolly had her own literacy program certainly added another facet to the gem of her humanity.

Dolly is familiar with the surprise that accompanies learning of her program and the “book lady” moniker she has among children. While she says adults are more used to thinking of her as a “painted lady,” she also claims kids are running to their mailboxes every month eagerly awaiting their books from Dolly. The Imagination Library is quite simple. If a child lives in an area with program sponsorship, they can receive one free book per month.

The books start at birth and end at age 5, the age when children typically start kindergarten. The first book the child receives is a customized version of The Little Engine That Could, Dolly’s personal favorite. The last book for American children in the program is, fittingly, Look out Kindergarten, Here I Come! The books come addressed to the child themselves. There is no fee to enroll, nor any qualifications other than living where the program is sponsored.

In 2019, the Imagination Library sent over 17,000,000 books to youth. Children in all 50 U.S. states receive books as well as children in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, and Australia. The program continues to grow, in both domestic and international reach. It’s quite a monumental undertaking, which raises the question, why is it again that it’s Dolly Parton who does all this?

Dolly is familiar with the surprise that accompanies learning of her program and the “book lady” moniker she has among children. While she says adults are more used to thinking of her as a “painted lady,” she also claims kids are running to their mailboxes every month eagerly awaiting their books from Dolly. The Imagination Library is quite simple. If a child lives in an area with program sponsorship, they can receive one free book per month.

The books start at birth and end at age 5, the age when children typically start kindergarten. The first book the child receives is a customized version of The Little Engine That Could, Dolly’s personal favorite. The last book for American children in the program is, fittingly, Look out Kindergarten, Here I Come! The books come addressed to the child themselves. There is no fee to enroll, nor any qualifications other than living where the program is sponsored.

In 2019, the Imagination Library sent over 17,000,000 books to youth. Children in all 50 U.S. states receive books as well as children in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, and Australia. The program continues to grow, in both domestic and international reach. It’s quite a monumental undertaking, which raises the question, why is it again that it’s Dolly Parton who does all this?

The Imagination Library also does plenty of promotional work. In 2017, Dolly released a children’s album, I Believe In You, whose proceeds benefit the library. The same year, Tennessee residents began ordering license plates with Dolly’s face, each sending $35 to the Imagination Library’s coffers. Imagination Library author Danica McKellar even name drops the Imagination Library in the Hallmark Channel movie Christmas at Dollywood.

It takes more than promotion to grow, of course. In 2011, the Imagination Library added audiobooks and braille books. Dolly has acknowledged in interviews that she knows the program will have to change with the times. Deep down, she wants kids to feel special, and she means all kids. That necessitates accommodating needs and differences. She delights in the idea of children receiving physical books through the postal system, and she wants that to remain the core function of the program. Still, as someone whose career has spanned radio shows to Netflix originals, she’s not naive to the fact that the program will have to evolve.

Dolly is proud of where she’s from, she’d proud to be in a position to help people, and she takes immense pride in the Imagination Library. Her father lived to see the first five years of the program. She says he was probably more proud of the Imagination Library than her superstardom. One of the things that makes her the proudest of the program is its longevity, with some of the earliest recipients of books having their own children in the program now. She also takes perverse delight in angry letters she receives from the 6-year-olds who have aged out of the program.

The Imagination Library also does plenty of promotional work. In 2017, Dolly released a children’s album, I Believe In You, whose proceeds benefit the library. The same year, Tennessee residents began ordering license plates with Dolly’s face, each sending $35 to the Imagination Library’s coffers. Imagination Library author Danica McKellar even name drops the Imagination Library in the Hallmark Channel movie Christmas at Dollywood.

It takes more than promotion to grow, of course. In 2011, the Imagination Library added audiobooks and braille books. Dolly has acknowledged in interviews that she knows the program will have to change with the times. Deep down, she wants kids to feel special, and she means all kids. That necessitates accommodating needs and differences. She delights in the idea of children receiving physical books through the postal system, and she wants that to remain the core function of the program. Still, as someone whose career has spanned radio shows to Netflix originals, she’s not naive to the fact that the program will have to evolve.

Dolly is proud of where she’s from, she’d proud to be in a position to help people, and she takes immense pride in the Imagination Library. Her father lived to see the first five years of the program. She says he was probably more proud of the Imagination Library than her superstardom. One of the things that makes her the proudest of the program is its longevity, with some of the earliest recipients of books having their own children in the program now. She also takes perverse delight in angry letters she receives from the 6-year-olds who have aged out of the program.

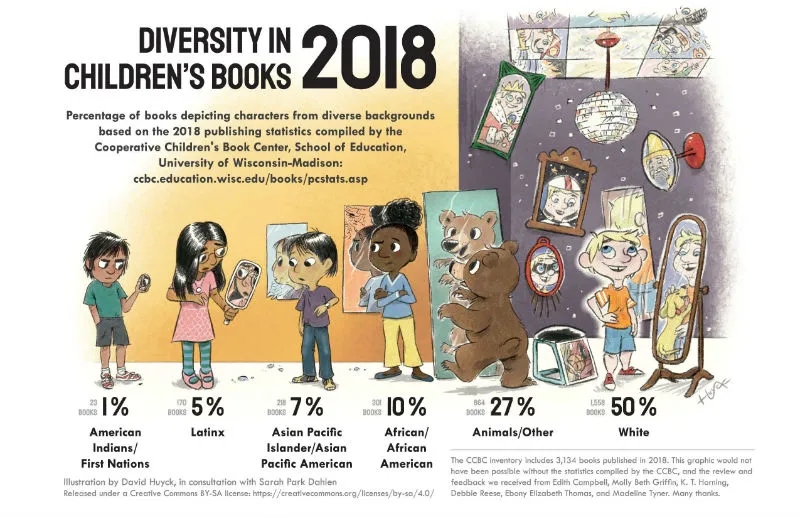

Among the CCBC’s takeaways from analyzing children’s books across years is the observation that “Small, independently owned publishers, such as Lee & Low and Just Us Books, and Groundwood contribute significantly to the body of authentic multicultural literature for children in the United States.” The Imagination Library has deprived themselves of these choices.

Among the CCBC’s takeaways from analyzing children’s books across years is the observation that “Small, independently owned publishers, such as Lee & Low and Just Us Books, and Groundwood contribute significantly to the body of authentic multicultural literature for children in the United States.” The Imagination Library has deprived themselves of these choices.

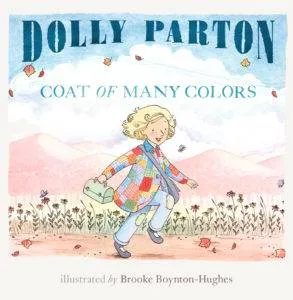

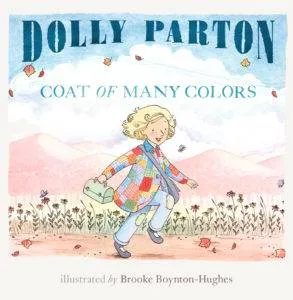

Coat of Many Colors, a picture book of Dolly’s song, is one every child participating in the Imagination Library receives. It joined the Library of Congress’s collection on the occasion of the 100,000,000th Imagination Library book. Moreover, Dolly says the song is her favorite among the over 3,000 she’s written in her life.

Dolly wrote the song and the book to honor her mother. She made young Dolly a colorful coat from scrap fabric and told her the biblical tale of Joseph and the coat of many colors. Dolly’s mother intended to instill pride in Dolly despite the less than glamorous garment. The coat showed favor upon Dolly as Joseph’s did, but unfortunately Dolly found herself ridiculed wearing it. She rose above. The material poverty Dolly faced meant little when weighed against the love she experienced, we learn. Dolly says the book can be taught in classrooms to combat bullying. She wants it to be a tale that helps readers stay strong despite however they deviate from the norm. We have plenty more recommendations on that theme.

It’s a nice story, except one particular lyric, “One is only poor only if they choose to be,” will trip up anyone skeptical of bootstrapping narratives. Or the pernicious falsehood the song perpetuates: only bad people are poor, so if you’re not bad you must also not be poor. Why not send kids Ron’s Big Mission, in which a young Ron McNair recognizes injustice and takes action? Why not a book like Night Job, which gives a tender glimpse into a parent-child relationship and low wage work? Dolly certainly doesn’t mean to cause harm with her book, but nostalgia can be toxic, and her coat does seem to be mighty rose-colored.

Coat of Many Colors, a picture book of Dolly’s song, is one every child participating in the Imagination Library receives. It joined the Library of Congress’s collection on the occasion of the 100,000,000th Imagination Library book. Moreover, Dolly says the song is her favorite among the over 3,000 she’s written in her life.

Dolly wrote the song and the book to honor her mother. She made young Dolly a colorful coat from scrap fabric and told her the biblical tale of Joseph and the coat of many colors. Dolly’s mother intended to instill pride in Dolly despite the less than glamorous garment. The coat showed favor upon Dolly as Joseph’s did, but unfortunately Dolly found herself ridiculed wearing it. She rose above. The material poverty Dolly faced meant little when weighed against the love she experienced, we learn. Dolly says the book can be taught in classrooms to combat bullying. She wants it to be a tale that helps readers stay strong despite however they deviate from the norm. We have plenty more recommendations on that theme.

It’s a nice story, except one particular lyric, “One is only poor only if they choose to be,” will trip up anyone skeptical of bootstrapping narratives. Or the pernicious falsehood the song perpetuates: only bad people are poor, so if you’re not bad you must also not be poor. Why not send kids Ron’s Big Mission, in which a young Ron McNair recognizes injustice and takes action? Why not a book like Night Job, which gives a tender glimpse into a parent-child relationship and low wage work? Dolly certainly doesn’t mean to cause harm with her book, but nostalgia can be toxic, and her coat does seem to be mighty rose-colored.

The Basics

Dolly is familiar with the surprise that accompanies learning of her program and the “book lady” moniker she has among children. While she says adults are more used to thinking of her as a “painted lady,” she also claims kids are running to their mailboxes every month eagerly awaiting their books from Dolly. The Imagination Library is quite simple. If a child lives in an area with program sponsorship, they can receive one free book per month.

The books start at birth and end at age 5, the age when children typically start kindergarten. The first book the child receives is a customized version of The Little Engine That Could, Dolly’s personal favorite. The last book for American children in the program is, fittingly, Look out Kindergarten, Here I Come! The books come addressed to the child themselves. There is no fee to enroll, nor any qualifications other than living where the program is sponsored.

In 2019, the Imagination Library sent over 17,000,000 books to youth. Children in all 50 U.S. states receive books as well as children in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, and Australia. The program continues to grow, in both domestic and international reach. It’s quite a monumental undertaking, which raises the question, why is it again that it’s Dolly Parton who does all this?

Dolly is familiar with the surprise that accompanies learning of her program and the “book lady” moniker she has among children. While she says adults are more used to thinking of her as a “painted lady,” she also claims kids are running to their mailboxes every month eagerly awaiting their books from Dolly. The Imagination Library is quite simple. If a child lives in an area with program sponsorship, they can receive one free book per month.

The books start at birth and end at age 5, the age when children typically start kindergarten. The first book the child receives is a customized version of The Little Engine That Could, Dolly’s personal favorite. The last book for American children in the program is, fittingly, Look out Kindergarten, Here I Come! The books come addressed to the child themselves. There is no fee to enroll, nor any qualifications other than living where the program is sponsored.

In 2019, the Imagination Library sent over 17,000,000 books to youth. Children in all 50 U.S. states receive books as well as children in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, and Australia. The program continues to grow, in both domestic and international reach. It’s quite a monumental undertaking, which raises the question, why is it again that it’s Dolly Parton who does all this?

Reading and Religion

There are a few important things to know about Dolly Parton that will make the Imagination Library make perfect sense. First, she is herself an avid reader. She considers herself a “book a week” reader and says she does some of her best thinking when she’s reading. She also says she always loved books but hated school, which certainly sheds some light on why the books go directly into kids’ hands. Fundamentally, Dolly is a deeply religious woman, who believes her work should uplift people and glorify God. Her faith greatly influences the Imagination Library. Specifically, the commandment about honoring one’s father and mother comes up a lot when Dolly talks about her work for the program.Dolly Logic

The Imagination Library relates to her parents in different, specific ways. Dolly speaks of her father’s illiteracy very openly, as well as his keen intelligence, and she wonders what path his life might have taken had he had more opportunity for education. To Dolly, anything she can do to be a corrective force, increasing literacy among the population, is honoring her father. According to Dolly, there were too many drooly, unruly children around—she’s one of 12—to keep books safe and intact in the small cabin they all shared in Sevier County, Tennessee. Thus, the only book she had regular access to was the bible her mother read from when she was young. Her mother imbued bible stories with such wonder that Dolly’s love of reading was sparked then. She also realized that books are a pathway to learning, and perhaps more importantly to dreaming, regardless of geographic isolation or poverty. Giving very young children books, books meant for loved ones to read aloud, honors her mother. Dolly Parton does not have children herself. When pressed about this (something I personally wish interviewers would not do), Dolly says children were not in God’s plan for her. She adds to that some special Dolly logic: that having no children of her own renders all children hers. Thank goodness for Dolly logic, because her sense of responsibility to children broadly is what has allowed the Imagination Library to be the global effort it is now.The Little Program

One of Dolly Parton’s verbal tics you will notice if you watch enough of her interviews is the word little. She’ll describe the picture book based on her song “Coat of Many Colors” as “a little book,” or she’ll describe one of her many, many hit singles as a “little song.” She will also say that he doesn’t do little. She says this while joking about her altitudinous wigs, outsized personality, and her other attributes she rarely fails to mention. It’s not contradictory, exactly. Or if it is, there’s no one more comfortable taking seemingly contradictory stances—or judiciously avoiding taking any stance, in the case of politics—as Dolly Parton. Dolly says she never knows what songs are going to catch on. The same applies to charity programs. Ultimately, everything has to start little before it gets big, including the Imagination Library. The Dollywood Foundation, whose flagship program is the Imagination Library, has a primary goal to inspire children’s educational aspirations. Their first little program in the early 1990s, called the Buddy Program, promised middle schoolers $500 if they graduated from high school. The dropout rate for the two classes promised the graduation bonus fell from 35% to 6%.The Big Program

The Buddy Program did not gain a lot of traction. In 1995, the Imagination Library launched, providing books to children only in Sevier County, Tennessee, Dolly’s own home county. She talks and jokes of her childhood constantly; she sings of her Tennessee Mountain Home. A replica of her childhood home, which lacked running water and electricity, stands at Dollywood, Dolly’s own theme park in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee. Part of honoring her parents means honoring her upbringing. People sometimes assume the program is only for low income or otherwise underserved youth, though it’s not. The 1990 census reported the rate of poverty in Sevier County, Tennessee was a bit over 13%. Currently it’s at 15.3%, higher than the national average of 13.1%. Needless to say, those percentages are all far too high. If you apply Dolly Logic, however, it’s easy to see why the program would start small but also be universal: what part of all children are Dolly’s children was unclear?Universality

People can debate the merits of means-tested and universal programs. I personally appreciate that public libraries are universal programs in the United States, helping me from blowing my book budget. I’ve also seen firsthand some of the indignities that come with means-tested programs. When I worked for an education nonprofit, my organization risked losing funding if we served too many children who were not recipients of free school lunch or who were not U.S. citizens. The very first interactions with the youth I served involved incredibly invasive paperwork asking for social security numbers and parents’ occupations. It did not, to say the least, instill trust. So I am very glad no one has to send Dolly Parton their tax returns in exchange for picture books. Dolly clearly has a penchant for universal programs. Following the wildfires in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, in late 2016, the Dollywood Foundation set up the My People Fund, to provide direct assistance on a monthly basis to those affected by the fires. This program has since been studied as a model of how Universal Basic Income works. As with the Imagination Library, income had no effect on the monetary help dispensed to Gatlinburg residents.Dolly Parton, Social Scientist

Studies about literacy that postdate The Imagination Library have shown something Dolly intuited. That having books at home matters. A study in 2010 details how “home library size has a very substantial effect on educational attainment.” Children are found to benefit from books at home regardless of socioeconomic status. The Imagination Library itself has been studied, and the results show children “who participated in the program had greater letter knowledge and higher scores on measures of phonological awareness” than their Dolly-less peers. Universal basic income, early intervention in childhood literacy—what social problem should Dolly take on next?Expansion

The 1990 Census has the under-5 population of Sevier County at just over 3,100. The 2019 statistic of 17.1 million books means that over 1.4 million children are currently in the program. It takes a lot of buy-in to expand a program so drastically, and that’s exactly what has happened. In 2000, the foundation began an effort to replicate the program at a national level. In 2001, 27 affiliate programs launched in 11 states. By 2004, Tennessee’s governor pledged statewide coverage for the program. North Carolina followed suit in 2017. Canada hopped on the Imagination Library train in 2006, the first country outside the U.S., and Ireland joined just last year. For everyone living in the areas without statewide coverage, the program still works through affiliates. The Imagination Library selects the books, accepts the money to pay for them, and coordinates the shipping of them, but the recruitment of children and fundraising for the cost of the books happen at local levels. The books cost $2.10 per child, per month. The local affiliate spearheading the effort might be a school district, a business, or a service organization like a Rotary Club.Evolution

The Imagination Library also does plenty of promotional work. In 2017, Dolly released a children’s album, I Believe In You, whose proceeds benefit the library. The same year, Tennessee residents began ordering license plates with Dolly’s face, each sending $35 to the Imagination Library’s coffers. Imagination Library author Danica McKellar even name drops the Imagination Library in the Hallmark Channel movie Christmas at Dollywood.

It takes more than promotion to grow, of course. In 2011, the Imagination Library added audiobooks and braille books. Dolly has acknowledged in interviews that she knows the program will have to change with the times. Deep down, she wants kids to feel special, and she means all kids. That necessitates accommodating needs and differences. She delights in the idea of children receiving physical books through the postal system, and she wants that to remain the core function of the program. Still, as someone whose career has spanned radio shows to Netflix originals, she’s not naive to the fact that the program will have to evolve.

Dolly is proud of where she’s from, she’d proud to be in a position to help people, and she takes immense pride in the Imagination Library. Her father lived to see the first five years of the program. She says he was probably more proud of the Imagination Library than her superstardom. One of the things that makes her the proudest of the program is its longevity, with some of the earliest recipients of books having their own children in the program now. She also takes perverse delight in angry letters she receives from the 6-year-olds who have aged out of the program.

The Imagination Library also does plenty of promotional work. In 2017, Dolly released a children’s album, I Believe In You, whose proceeds benefit the library. The same year, Tennessee residents began ordering license plates with Dolly’s face, each sending $35 to the Imagination Library’s coffers. Imagination Library author Danica McKellar even name drops the Imagination Library in the Hallmark Channel movie Christmas at Dollywood.

It takes more than promotion to grow, of course. In 2011, the Imagination Library added audiobooks and braille books. Dolly has acknowledged in interviews that she knows the program will have to change with the times. Deep down, she wants kids to feel special, and she means all kids. That necessitates accommodating needs and differences. She delights in the idea of children receiving physical books through the postal system, and she wants that to remain the core function of the program. Still, as someone whose career has spanned radio shows to Netflix originals, she’s not naive to the fact that the program will have to evolve.

Dolly is proud of where she’s from, she’d proud to be in a position to help people, and she takes immense pride in the Imagination Library. Her father lived to see the first five years of the program. She says he was probably more proud of the Imagination Library than her superstardom. One of the things that makes her the proudest of the program is its longevity, with some of the earliest recipients of books having their own children in the program now. She also takes perverse delight in angry letters she receives from the 6-year-olds who have aged out of the program.

The Flaws in the Gem

People are very quick to canonize Dolly even while she’s still earthbound. I’ve probably called her Saint Dolly myself. Dolly, however, would probably be the first to tell you she’s not above critique, and neither is her program. There are easy nits to pick. A glaring one: why aren’t there more language options? Also, a stable mailing address month to month is a privilege all too many children lack. Of course, free books for transient or unhoused kids probably matters less than food, clothing, education, healthcare. It’s a problem perhaps too big for even Dolly to tackle on her own. Additionally, the Dollywood Foundation is not as transparent as they could be about their finances. This keeps them at three stars out of four on the assessment website Charity Navigator. One big problem to confront, as Jessica Wilkerson so beautifully argues in her essay “Living with Dolly Parton,” is Dolly’s “blinding, dazzling whiteness.”The Unbearable Whiteness of Children’s Books

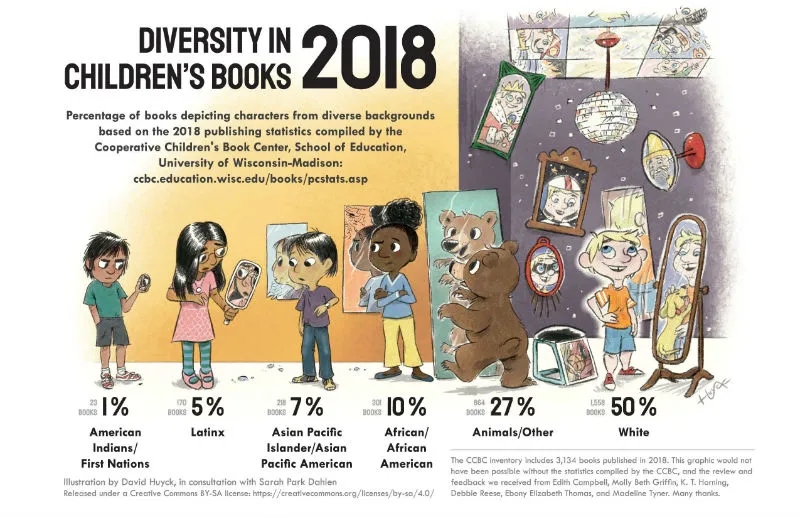

In 2000, the Imagination Library undertook negotiations with publishers to stabilize or minimize the ratio between cost and quality. The result was a partnership with Penguin Putnam (now Penguin Random House). For a program that is giving away over one million books per month, streamlining makes sense. It means, however, that they’ve saddled themselves with only one publisher’s vision for what young kids should be reading. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center, a research library of the School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, regularly publishes statistics about the state of diversity in Children’s Books. The infographics based on their finding display the grim fact that a randomly selected children’s book is more likely to have an animal or a truck for a main character than a character who is black, indigenous, or a person of color. Among the CCBC’s takeaways from analyzing children’s books across years is the observation that “Small, independently owned publishers, such as Lee & Low and Just Us Books, and Groundwood contribute significantly to the body of authentic multicultural literature for children in the United States.” The Imagination Library has deprived themselves of these choices.

Among the CCBC’s takeaways from analyzing children’s books across years is the observation that “Small, independently owned publishers, such as Lee & Low and Just Us Books, and Groundwood contribute significantly to the body of authentic multicultural literature for children in the United States.” The Imagination Library has deprived themselves of these choices.

The Faces of the Imagination Library

The books in the Imagination Library, however, do not represent a random sampling of Penguin Random House’s catalog. There is a highly qualified committee choosing the selections for the Imagination Library. They choose books to keep pace with the development of children as they grow from babies to kindergartners. They don’t, however, seem to be substantially more invested in authentically diverse children’s books than publishing as a whole. Just about half of 2020’s selections feature animals or anthropomorphized inanimate objects as main characters. By my assessment, about 20% of the remaining books feature white main characters. Of the remaining books, there are certainly excellent choices: a Coretta Scott King honor, a Pura Belpré honor, the book version of the Oscar-winning animated short Hair Love, a book by prolific Abenaki author Joseph Bruchac, among others. Still, there are books on the list featuring characters of color written by white authors, like Ezra Jack Keats’s classic The Snowy Day. All this is to say that publishing can do better, and the selection committee can do better.Dolly’s Problematic Fave

Coat of Many Colors, a picture book of Dolly’s song, is one every child participating in the Imagination Library receives. It joined the Library of Congress’s collection on the occasion of the 100,000,000th Imagination Library book. Moreover, Dolly says the song is her favorite among the over 3,000 she’s written in her life.

Dolly wrote the song and the book to honor her mother. She made young Dolly a colorful coat from scrap fabric and told her the biblical tale of Joseph and the coat of many colors. Dolly’s mother intended to instill pride in Dolly despite the less than glamorous garment. The coat showed favor upon Dolly as Joseph’s did, but unfortunately Dolly found herself ridiculed wearing it. She rose above. The material poverty Dolly faced meant little when weighed against the love she experienced, we learn. Dolly says the book can be taught in classrooms to combat bullying. She wants it to be a tale that helps readers stay strong despite however they deviate from the norm. We have plenty more recommendations on that theme.

It’s a nice story, except one particular lyric, “One is only poor only if they choose to be,” will trip up anyone skeptical of bootstrapping narratives. Or the pernicious falsehood the song perpetuates: only bad people are poor, so if you’re not bad you must also not be poor. Why not send kids Ron’s Big Mission, in which a young Ron McNair recognizes injustice and takes action? Why not a book like Night Job, which gives a tender glimpse into a parent-child relationship and low wage work? Dolly certainly doesn’t mean to cause harm with her book, but nostalgia can be toxic, and her coat does seem to be mighty rose-colored.

Coat of Many Colors, a picture book of Dolly’s song, is one every child participating in the Imagination Library receives. It joined the Library of Congress’s collection on the occasion of the 100,000,000th Imagination Library book. Moreover, Dolly says the song is her favorite among the over 3,000 she’s written in her life.

Dolly wrote the song and the book to honor her mother. She made young Dolly a colorful coat from scrap fabric and told her the biblical tale of Joseph and the coat of many colors. Dolly’s mother intended to instill pride in Dolly despite the less than glamorous garment. The coat showed favor upon Dolly as Joseph’s did, but unfortunately Dolly found herself ridiculed wearing it. She rose above. The material poverty Dolly faced meant little when weighed against the love she experienced, we learn. Dolly says the book can be taught in classrooms to combat bullying. She wants it to be a tale that helps readers stay strong despite however they deviate from the norm. We have plenty more recommendations on that theme.

It’s a nice story, except one particular lyric, “One is only poor only if they choose to be,” will trip up anyone skeptical of bootstrapping narratives. Or the pernicious falsehood the song perpetuates: only bad people are poor, so if you’re not bad you must also not be poor. Why not send kids Ron’s Big Mission, in which a young Ron McNair recognizes injustice and takes action? Why not a book like Night Job, which gives a tender glimpse into a parent-child relationship and low wage work? Dolly certainly doesn’t mean to cause harm with her book, but nostalgia can be toxic, and her coat does seem to be mighty rose-colored.