Stories for Everyone: Mythology in Comics and the Push for More Diverse Stories

When you hear the word “mythology,” your thoughts may drift to stories of Greco-Roman gods seducing humans, squabbling over infidelities, or getting into epic wars. Or maybe you think of the violent battles (and occasional cross-dressing) of the Norse gods, which are fated to end with the apocalypse called Ragnarok.

But the world of mythology is much richer and broader than that. So why do our imaginations — and the imaginations of Western comic book creators — always seem to go that far and no farther? Are there creators from other countries working to bring their folktales, fairytales, and myths to a wider audience?

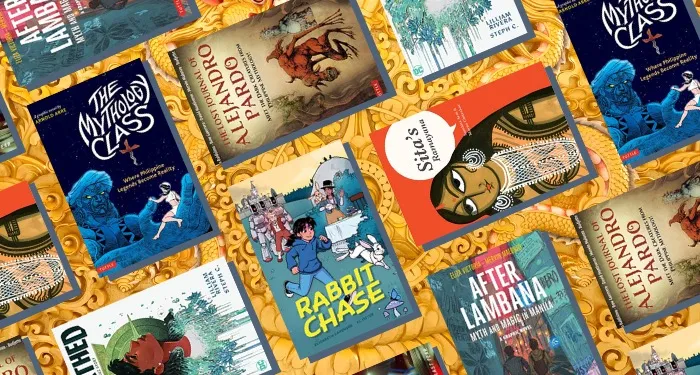

Fortunately for mythology lovers like myself, the answer to that last question is yes. I had the pleasure of interviewing three Filipino creators — Arnold Arre (The Mythology Class), Paolo Chikiamco (Muros, with art by Borg Sinaban), and Eliza Victoria (After Lambana, with art by Mervin Malonzo) — whose mythology-inspired works are now being brought to a wider American audience by Tuttle Publishing. Their answers illuminate not just what inspired them to incorporate Philippine mythology into their comics, but also what impact their — and other — works can have on readers.

Mythology in American Comics

Western comics have been adapting mythological stories for decades. Many early comics devoted themselves to introducing young readers to classic tales, from Ivanhoe and Robin Hood to mythological tales like the fall of Icarus or the labors of Hercules.

The most famous usage of mythology in Western comics is, of course, in superhero comics. This usage, too, goes back to the earliest days of comicdom: DC now owns Wonder Woman and Shazam, both of whom share close links with the Greco-Roman gods, while Marvel’s reinterpretation of the Norse gods (Thor and Loki in particular) has eclipsed the original versions in the popular imagination.

Thus began a long tradition of comics bringing mythological characters into the present day, which titles like The Wicked + The Divine and Lore Olympus have kept going. Paolo Chikiamco discusses this in the introduction to Alternative Alamat, an anthology he edited of prose stories that reinterpret Philippine myths for modern times:

[Mythical gods and heroes] come from a time far different from our own, and for them to live again in the hearts and minds of those of us in the present, their stories much be retold… The gods adapt, when they are embodied in new forms. The gods change, and so they survive.

Not every comic takes this approach, of course. Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology retells the Norse myths as they were handed down to us from sources like the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda.

Mythology in Philippine Comics

As the history of Filipino comics — or komiks, as it is rendered there — is not a topic I know much about, I was very grateful for the opportunity to learn about it from creators who not only saw it happen, but have also played a role in shaping how the industry has developed in recent years.

So what about komiks, anyway? How have they historically adapted mythology for their readers?

They didn’t, for the simple reason that Filipino comics didn’t really exist on a wide scale until recently. Local creators were often shut out by the popularity of American comics and Japanese manga. Chikiamco confirmed this to me, saying that komiks “were not readily available” when he was a kid.

Arnold Arre cites “exposure to both Western and Japanese comics” as the means by which he developed his own distinctive art style. He also explained more about the komiks industry he knew while growing up and, later, upon entering the industry himself:

Back in the 1970s, Tagalog comics were serialized in 10- to 20-page installments that came out monthly in comics magazines such as Liwayway. The popular stories consisted of human drama, comedy capers, and sword & sorcery epics.

In the late ‘80s throughout the ‘90s, the scene was dominated by book shops that sold Marvel and DC comics. Unfortunately, most of the old Tagalog comics were difficult to come by at this time and their publishers struggled to stay afloat.

Eliza Victoria also shared her experiences with komiks while growing up:

I grew up in the 1990s, a time when there was a proliferation of local komiks titles printed in newsprint that you can buy for cheap. I remember reading a lot of comic anthology collections such as Tagalog Klasiks or Hiwaga, where some stories would feature creatures from Filipino folklore. I remember them being loud, bombastic stories, with striking illustrations of monsters.

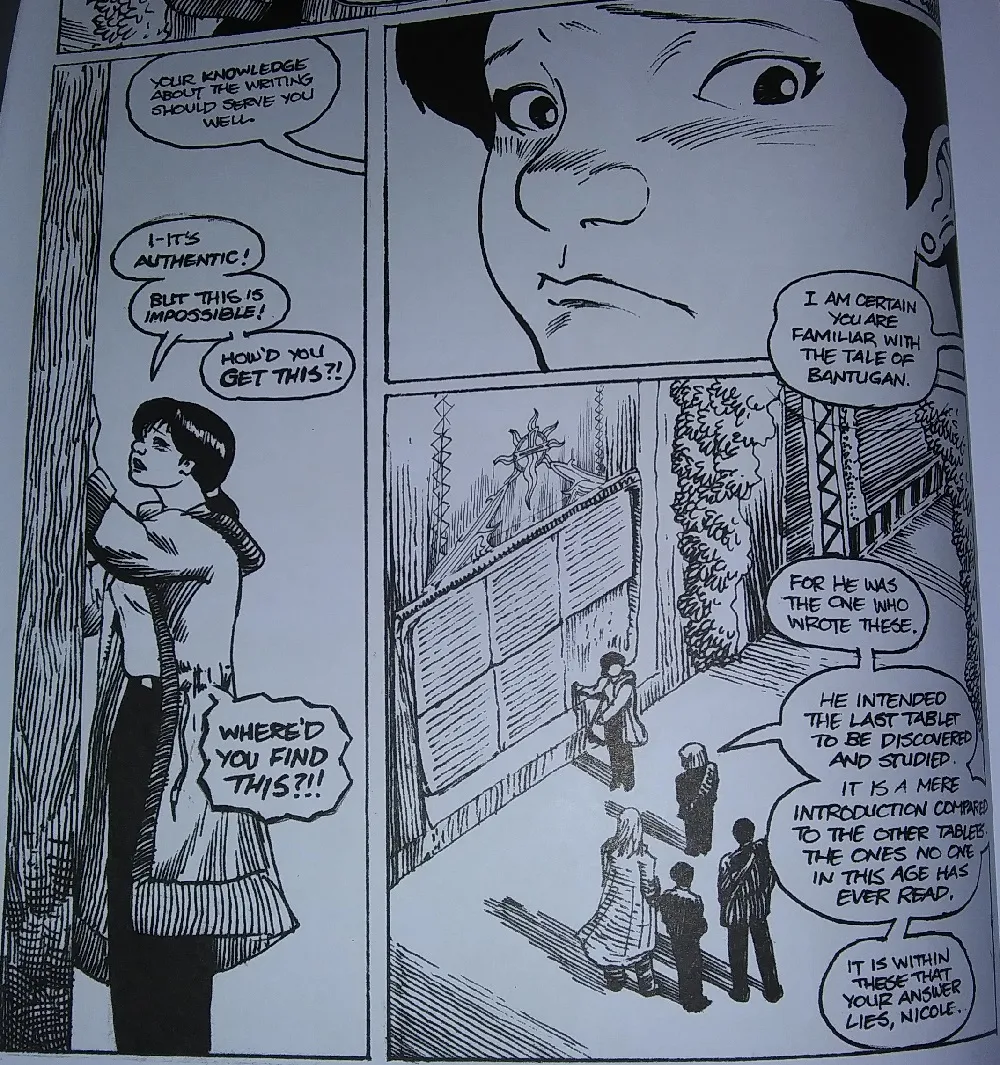

When did komiks really start to become interested in myths? In part, we can thank Arre’s sprawling, 300-plus-page epic The Mythology Class. First published in 1997, it follows an eclectic group of young people who are summoned by mythological heroes of old to help fight enkantos, here depicted as troublesome creatures who have invaded our world and must be sent back to their own dimension.

“I actually had doubts about reintroducing Philippine mythology to the local scene because most of my peers were into the superhero genre,” Arre told me. “In hindsight, I’m happy that I took that risk because now, it’s great to see the younger generation appreciating and even creating Philippine mythology stories.”

Chikiamco is one of those creators who were influenced by Arre’s groundbreaking work: “[The Mythology Class] was the first time I’d seen Philippine mythology and folklore depicted not as objects of horror or camp but as parts of a secondary world, a parallel space, one which could be understood rather than feared.”

The success of The Mythology Class, along with the rising popularity of komikons that allowed readers and creators to gather in one place, helped komiks finally gain the respect and prominence necessary to start adapting myth-based stories for wider audiences.

An Exclusive Club

By now, you may be asking: why was a concerted effort necessary to get Philippine myths into comics? Why do so many myth-based comics focus exclusively on Norse, Greek, and Roman gods instead of mining mythological tales from other cultures?

Frankly, it’s probably because they’re from white-majority societies. I’m not saying the comics creators were intentionally racist, but rather that they were most familiar with Norse and Greco-Roman mythologies because that is what gets taught in schools and published in books. Greek and Roman societies in particular are held up as the cradle of Western culture and human development, and they are therefore more “worthy” of preservation and study.

Chikiamco told me that, when he was first discovering books about mythology as a child, “those were always books on Western mythology, primarily Greek with the occasional Norse collection thrown in for good measure. Books on Philippine mythology existed, but for the most part were not available in the bookstores – many were out-of-print and/or aimed at scholars rather than children or the casual enthusiast.”

Victoria confirmed this when she told me that some Philippine mythological figures live on through stories told to children by older relatives, but many others have become an academic subject to be covered, if only “very briefly,” in the classroom.

“So in my head,” she said, “Philippine mythology equals school lessons, whereas you turn to American pop culture and you have Hercules the Disney film and Hercules the TV series and Loki and Thor and so on and so forth.”

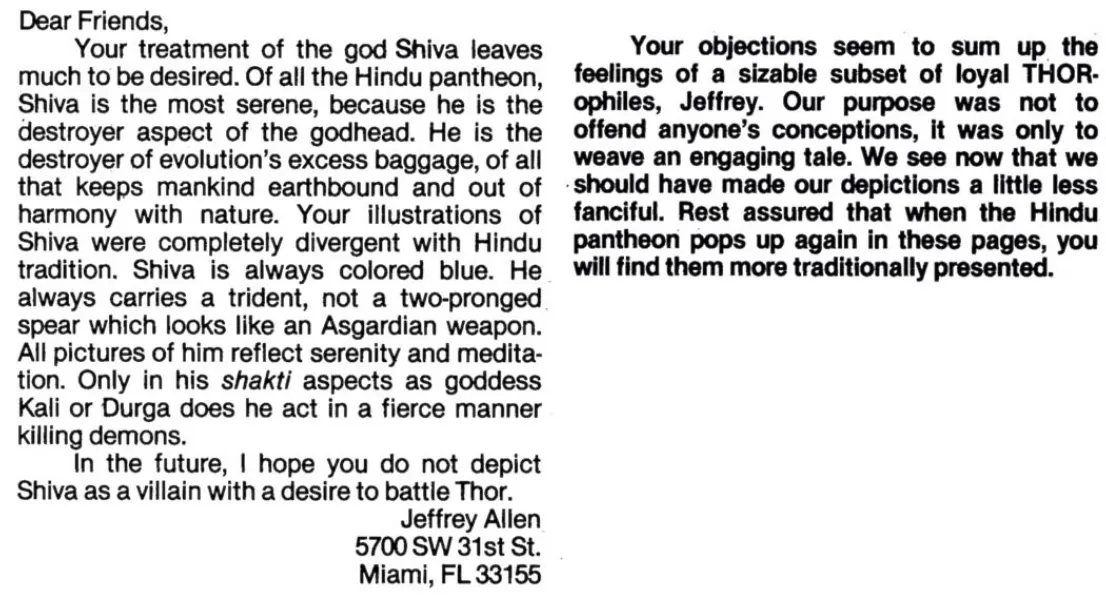

Over the years, Marvel made a few token attempts at introducing figures from other cultures, but it often went wrong. X-Men #140 featured an Indigenous creature that should never be adapted, ever, while fans criticized Thor #301’s use of the Hindu gods. (To be fair, Marvel took the criticism to heart, which is a lot better than their previous reaction to being called out for racism. Note how they don’t actually apologize, though.)

A Mythical Future

Happily, modern comics are starting to branch out a little more, allowing more diverse creators to tell stories from a wider range of cultural traditions. The Filipino books I’ve discussed here are just the tip of the iceberg: we now also have Rabbit Chase (which incorporates Anishinaabe folklore) Unearthed: A Jessica Cruz Story (Mexican), Sita’s Ramayana (Indian), and other comics that adapt ancient tales for a modern audience.

The future of mythology in comics is looking much brighter than it did just a few years ago. But so what? Mythology is cool and all, but why should we concern ourselves with how it is portrayed, or even who is portrayed and who isn’t?

As hinted at by Marvel’s Shiva debacle, mythologies are not dead stories: they are living, evolving parts of many cultures. While I have been referring to all of these comics as “mythology,” it is important to recognize the variety of meaning within that word.

“If you hop on Wikipedia,” Victoria told me, “you’ll see the Sirena and so on listed under ‘mythological races,’ but when you hear my relatives speak about them, they’re not in the realm of myths, they’re still very much around.”

While these legends and folktales may still be alive, they are often also endangered. As Victoria pointed out, “So much of our oral stories have been lost, and many of our regional languages are starting to die. I’ve always admired stories that incorporate multiple Filipino languages because they keep these languages, and stories, alive.”

“Philippine folklore is very rich with stories and I feel that there are so many that still need to be told and retold,” added Arre.

And that is the ultimate value of mythology-based comics: enabling stories that have been told for centuries to live on in the hearts and imaginations of new generations, and the generations after that. Chikiamco put it poignantly when he said, “My wish is only that there be more kinds of comics and more sources of myth, so that everyone who wants to will be able to find a story that speaks to them, that represents them, that completes them and challenges them.”

The gods change, and so they survive.