The Current State of Disability Representation in Children’s Books

I began this piece out of frustration. Despite the many initiatives to make children’s books more diverse and representative of everyone instead of a select white, able-bodied, cis het population, it’s still hard to find disability representation in children’s books, particularly ones written by disabled folk, and particularly ones that depict multiple identities (Black and disabled, for example). What’s happening in the children’s publishing industry? I wondered. Are there truly so few books with disabled characters being published? Are things getting any better? What are children’s publishing companies doing to be more inclusive of disabled folk?

I decided to find out, and spoke to numerous authors and publishers about disabled representation in the children’s book publishing industry. What I discovered is both heartening and worrying. Yes, in many respects, things are improving in terms of disabled representation in children’s books. But there are still many gaps in representation and a lack of both understanding and specific initiatives among some (though not all) publishers.

The Stats On Disabled Representation In Children’s Books

According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s 2019 study, only 3.4% of children’s books have disabled main characters. Compare this statistic with the CDC’s finding that 26% of Americans have disabilities, and it’s easy to see there’s a problem. The children’s book industry is failing to portray the many myriads of ways bodies and people exist and interact with the world. These are ways that many children experience themselves or will experience in the future.

This lack of representation extends to publishing companies as well. Since 2015, Lee & Low Books has tracked diversity within the publishing industry. Their 2019 study had 11% of responders identifying as disabled. This is a marked improvement from their 2015 study, which had only 4% of responders identifying as disabled. But they note this is most likely due to their rephrasing of the question and because of changes in how society in general looks at and defines mental-health issues, not necessarily because the publishing industry is hiring more disabled folk. Even with this increase, the number of disabled folk working in the publishing industry is less than half of the percentage of people who have disabilities in the United States.

Barriers Of Entry For Disabled Writers And Illustrators

In my interviews with various authors and illustrators, a few main themes came up when discussing barriers of entry into publication: Ableism, narrative stereotypes industry professionals have, characters with multiple identities, accessibility at writing conferences, and pushback from readers.

Ableism

Ableism is the intentional and unintentional discrimination against disabled people. These practices often make it difficult for disabled writers to break into the industry and, even once published, thrive and continue publishing. I spoke with Alaina Lavoie, the communications manager for We Need Diverse Books and adjunct professor at Emerson College, about the ways ableism presents itself in publishing.

“Literary agents and editors often turn down books with disabled main characters because they explain they ‘can’t connect to the story’ or don’t think the book has marketing potential,” she explained. “Once disabled creators do get a book deal, they often face ableism at other levels throughout the process. It may be that they’re challenged on book jacket copy, or not given a large promotional budget, or assumed to be a niche book for just a niche audience that isn’t seen as ‘mainstream.’ A lot of the ways that ableism shows up in publishing are subtle microaggressions, and disabled creators often have to continue to advocate for themselves and their work: To get printed ARCs [advanced review copies] made for accessibility reasons, to request accessible event venues for their in-person readings and events, to push for accessibility for online events, to have their work submitted for awards and to the media for promotion.”

At every step in the publishing process, from the initial spark to write to the accessibility of ARCs, disabled creators might face a challenge to their work and their disabled identities.

Stereotyping Disabled Narratives

One major ableist hurtle disabled writers face is, even once they’ve written a stellar book, having non-disabled publishing gatekeepers (from literary agents to editors) reject their book for not following certain stereotyped narrative arcs included in many popular books written by non-disabled writers.

Jen Malia, author of Too Sticky! Sensory Issues with Autism and Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing Coordinator at Norfolk State University, elaborates on the ableist, stereotyped narratives many readers — including publishing professionals — expect to see in books with disabled characters:

“[A] harmful stereotype that reappears over and over again in disabled literature is that disabled people are a burden to their families. It’s hard for disabled authors to publish authentic and positive representations in an industry that expects to see these stereotypes from non-disabled authors.”

This is why publishing narratives by disabled authors is so important.

An anonymous dyslexic author told me she’s had many editors ask her to include dyslexic stereotypes into her picture book manuscript. When she explains that what they want her to include are stereotypes and mostly untrue, they tell her they have trouble connecting to her work and reject it.

Another stereotyped narrative non-disabled readers expect to find is stories where the disabled person “overcomes” their disability. Kati Gardner, the author of Finding Balance, is currently battling this stereotype. “They [publishers] aren’t interested in messy, true-to-life, disabled stories,” she explained in a group chat of online disabled creators in the kid lit community. “They are only interested in the familiar tropes of overcoming adversity or death. There’s no in-between.”

Her statement was corroborated when I spoke to the VP of a major publishing house and she expressed the importance of readers, disabled and non-disabled alike, reading stories of people overcoming their disabilities. “How much better that person is after reading such a book,” she told me. As a gatekeeper in the publishing industry, she has the important job of determining which books by disabled creators get published. What happens to the disability narratives, then, where the disabled character has no desire to “overcome” their disability? Many in the disabled community embrace their disabled identities as part of their essential self. Also, what happens to the narratives where the disabled person doesn’t overcome their disability? Or where the story has nothing to do with their disability? Disability narratives are nuanced and complex and cannot and should not be forced into narrow narrative arcs. What she and other editors like her consider a “good” book with disability representation may be because it has the stereotyped narratives they enjoy. At the same time, they reject more nuanced books by disabled creators for failing to follow these ableist arcs.

Multiple Identities

Speaking of nuanced narratives, what happens when characters are, in addition to being disabled, also non-white and/or LGBTQ+?

“There still needs to be a lot more improvement, especially at the intersections of marginalized identities; most disability books still often feature the white, straight, cis perspective,” said Alaina Lavoie.

“It’s time we stop saying whiteness in every single category is the default,” added Keah Brown, the author of The Pretty One and the 2022 picture book Sam’s Super Seats. After the publication of The Pretty One, she received pushback within the disabled community for centering race in addition to disability. While The Pretty One is not a children’s title, with 85% of editorial boards in children’s publishing comprised of white folk, it’s no surprise that when children’s books are published with disabled main characters, those characters are almost always white.

James Catchpole, children’s book literary agent and author of What Happened to You?, told me he thinks “a lot of the barriers have to do with class, with social background, and who might be expected to be a children’s writer (and who can afford to be one…). And that intersects with disability and with race in various ways, meaning some communities are definitely underrepresented in the industry — some drastically so. Whereas if you’re an upper-middle-class white person with a good degree and a disability, like me, then that’s often not a hindrance.” While he was speaking specifically of the UK children’s publishing industry, in the United States, BIPOC are also less likely to earn a livable income, and considering the slow growth of racial diversity that’s also present in the children’s book industry, it’s safe to assume that disabled, non-white children’s book creators face additional hurdles to publishing their children’s books.

It does seem like some publishing companies are attempting to correct the “single identity” focus by actively seeking works from disabled creators like Jessica Lewis, who wrote the novel Meow or Never for Scholastic as an IP work under the name Jazz Taylor. The preteen main character in this charming middle grade novel is disabled, Black, and a lesbian.

Accessibility in Writing Conferences

Writing conferences are considered essential tools for many new writers. Conferences can provide craft lectures, sources for feedback, networking with agents and editors. This is the place many new writers find agents or feedback groups. Yet, many conferences are inaccessible for disabled writers in a variety of ways.

Deaf disability activist and prospective YA author Jenna Beacom told me that conferences remain largely inaccessible for her. She misses out on essential networking. While she’s asked for accessibility at some of the conferences she’s attended, she fears antagonizing the very people she’s supposed to be cultivating a writing relationship with. Instead, she’s turned to Twitter to make writing connections, but it takes a lot of her time and energy. She did applaud DVCon as being one of the only accessible conferences she’d ever attended and a source of inspiration for her current writing project. “[O]ne panel in particular,” she explained, “was so great that I credit it specifically with the fact that I’ve written about 50K words since, and am now very close to finishing my book.”

If she had been unable to attend that conference due to accessibility issues, then she would’ve missed out on much-needed inspiration.

While my disability doesn’t require many accommodations, I’ve experienced negative feedback from writing peers at conferences I’ve attended when I asked for accommodations. I was told by one writer multiple times that I was lazy for using the elevator. Another writer mocked me when I requested food changes at a conference banquet to prevent an allergic reaction, then spent the entire meal complaining I had better food than her and demanding the waiter serve her meals like mine. These scenarios, while minor, create discomfort and added stress to what should be a networking and craft-building experience. They also show ableism in the industry. Would a literary agent overhearing me discuss food allergies with a waiter assume I was “whining” and thus avoid signing me as a client? (To be clear, I wasn’t seeking an agent at the time.) Are writers who request accommodations for their disabilities perceived as being high maintenance and not worth working with? These are all issues that need to be addressed.

Improvements In Disabled Representation

Most of the writers and illustrators I spoke to have noticed improvements in disability representation. Jen Malia cited the increase in the number of #OwnVoices books leading to more authentic disabled representation. Alaina Lavoie talked about how the publishing industry is “expanding the scope to beyond just books centered around trauma and education (explaining disability at a 101 level) to books about disabled characters going on adventures, solving mysteries, playing sports, and more.”

Sarah Allen, middle grade author of What Stars Are Made Of, agrees. “In my opinion,” she explained, “disability representation is centered on giving writers with disabilities space to tell their stories. Whether those stories focus on the particular disability directly or incidentally, whether the genre is contemporary, fantasy, or something else entirely. While I’m just one person with one point of view, from what I’ve seen in the last several years, the space for these stories has only grown and grown. Children’s publishing as a whole seems to be more and more aware of the need for these stories and these authors, and the value of disability representation.”

In my own experience covering children’s books, it seems like 2020 and especially 2021 have seen a marked increase in disabled #OwnVoices children’s books. I’m interested in seeing what the Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s 2021 and 2022 studies will reflect.

As both an agent and an author, James Catchpole has a unique perspective from both sides of the industry.

“I think the industry is changing quickly to keep up with what feels like the rapid pace of change in society, in terms of making space for marginalised voices. I would say disability tends to lag behind race and gender, but there are signs of things shifting nonetheless,” he told me.

“To take an example I’ve recently heard, ten years ago a very celebrated picture book writer in the UK, with some personal experience of disability, had to twist her publisher’s arm to accept a story she’d written about disability.

“In contrast, four years ago, when I started showing an early draft of my book What Happened to You? to editors, they were receptive at least in theory, not because I had any pedigree as an author, but because I understood the craft as an agent, and because I had direct personal experience of my subject. (I think the book struggled to sell at that point because Karen and I hadn’t got it right yet!)

“Now that my book’s here and gaining some traction, a year on from the summer of Black Lives Matter (which really pushed the call for marginalised voices into the mainstream), I’m being actively asked by editors to send them stories by disabled writers. That’s quite a change in ten years.”

It’s interesting and important to note that he’s seen a marked increase in interest since the Black Lives Matter Movement. Uplifting marginalized voices for one group does help to uplift other marginalized voices, though specifically addressing some of the unique problems groups of people face is also important.

While it does seem like there’s an increase in the number of #OwnVoices children’s books with disabled main characters, there’s still a lot of room for improvement. As Raymond Antrobus, author of the picture book Can Bears Ski?, told me, “It still seems the industry is generally at pre-school level in how they think and talk about disability.” He did express hope, however. “People like Joyce Dunbar, Jillian Weise, Alice Wong, San Alland, Shelia Black, Ilya Kaminsky, Daniel Sluman, Khairani Barokka (just to name a few) have been present and engaged with the issues of ableism and writing and speaking against it for years. There is hope.”

Hopefully, publishers will be open to listening to these voices.

What Publishers Are Doing

To better understand what’s going on behind the scenes, I emailed 16 children’s book publishers. I asked them the same question: “I’m curious about what the people at X PUBLISHER are doing to promote disabled voices and to prevent ableism? Sensitivity readers, a commitment to publishing more disabled voices, and/or hiring more disabled voices?”

Only six publishers responded: Sourcebooks, Holiday House, Candlewick, Orca, Quarto, Running Press, and Delacorte. Five more responded they would relay my message to others, but I never heard back.

I received a variety of answers.

All six expressed a commitment to publish more disabled voices and listed some of their books with disabled main characters.

“We are thoughtful in representing kids with disabilities in our illustrated books and have worked closely with our authors and artists to make sure kids of all abilities and backgrounds are represented in our illustrations. We also welcome and look for books written by disabled voices and hope to increase our offerings there in future lists.” —Julie Matysik, Editorial Director at Running Press Kids

“Holiday House, along with our sister companies Peachtree Publishing and Pixel+Ink, continues to seek authors and illustrators who can illuminate the experiences of the neurodiverse and disabled communities.” —Derek Stordahl, the Vice President and General Manager of Holiday House Publishing Inc

Three publishers mentioned a commitment to depicting disabled characters even when the book isn’t specifically about disability (Orca, Running Press, Candlewick).

“I think the first and most immediate or visible places Orca is working to prevent ableism, promote disabled voices and increase disabled visibility in the children’s book industry is through incidental yet intentional representation in our books. And by this I mean our authors, illustrators, and designers are always making a concerted effort to ensure people with disabilities are present on the page. I am not referring only to books like The Disability Experience … but also picture books like When We Are Kind or We Wear Masks and others. We know how important it is for children — and adults — to see themselves reflected on the pages of the books they’re engaging with and we do not want anyone to miss that opportunity.” —Kennedy Cullen, Marketing Coordinator at Orca

“Because many Running Press Kids books include versatile texts that speak to groups of children, one way that we have been able to increase disability representation is through art direction. Our Creative Director, Frances Soo Ping Chow, has been instrumental in making sure that group scenes always include characters with a range of mobility enjoying themselves, playing, and engaging with the theme of the book.” —Running Press Kids

Three publishers mentioned working with sensitivity readers (Orca, Quarto, Delacorte).

“[A]ll of our titles (whether or not they center disabled characters) are run by sensitivity readers who make sure we are accurately reflecting the experiences of the people we are featuring. This specifically includes sensitivity readers who specialize in disability and ableism.” —Mel Schuit, Quarto Group

Both of the people I communicated with from Orca and Delacorte said they utilize disabled sensitivity readers on their books with disabled characters. Beverly Horowitz, Senior Vice President & Publisher at Delacorte, added that she frequently finds herself learning new things from her sensitivity readers.

Three publishers spoke of making the workplace more accessible (Orca, Candlewick, Delacorte).

“As for in office, we always hope that we can make the accommodations necessary to make working with Orca possible for anyone. It is important to us that we work to employ staff from a diversity of backgrounds so that all of our unique ways of engaging with the world can contribute to making books that serve a wide readership and illuminate the breadth of the human experience for all of our readers. Though our actual office, being a heritage building with lots of stairs, may present some accessibility issues for people, we do make sure that remote access is possible for anyone who requires it.” —Kennedy Cullen, Marketing Coordinator at Orca

“We are constantly striving to foster and maintain a mutually supportive work community where all individuals feel safe, welcome, and equally free to participate fully and express themselves, regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, physical ability, background, or any other protected and/or distinguishing characteristic with which they may identify.” —Candlewick Press

On the phone, Beverly Horowitz of Delacorte told me she imagines — now that it’s been proven that remote work is possible — that even once the company can return to the physical workplace they’ll remain remote, enabling more disabled people to work with the company. But she cited no specific initiatives or advocacy of remote work.

Two publishers mentioned making their books more accessible to everyone (Orca, Candlewick).

“We also believe the experience of reading should not be missed by anyone and so we continue to work on making our books as accessible as possible — in all meanings of the word. For us, that means additional features in several series of our print books like dyslexia-friendly fonts and cream-based paper to decrease the contrast for those with language-based learning difficulties, as well as a new collection of accessible audiobooks that include image descriptions.” —Orca

“We have licensed large print publishers to publish some of our books. And we have also licensed specialty publishers to create combination braille and illustrated editions of some of our picture books.” —Candlewick

Since my initial question did not mention making books accessible to readers, I imagine other publishers might also have similar initiatives.

Quarto mentioned disability-themed book lines.

“I also wanted to call attention to our SEN Superpowers series, which celebrates the positive traits associated with a range of common SEN (Special Education Needs) conditions, boosting the confidence and strength-awareness of children with those conditions, while also allowing for better understanding and positivity among their peers.”—Quarto

Candlewick mentioned staff training about ableism and disability.

“We were pleased to send 10 staff members including editors and designers to a Highlights Foundation month-long symposium this past October, which addressed ableism and where attendees deconstructed colonial thinking processes using youth literature, and discussed misrepresentations in books to develop action plans for resisting them. We’ve also provided groupwide deaf awareness training for Candlewick and Walker staff to coincide with the release of our book Can Bears Ski?.” —Candlewick

While I did not email Kokila, a division of Penguin Random House, Keah Brown told me she’s had a wonderful experience working with them on her forthcoming picture book Sam’s Super Seats, with every single editor from the Kokila team giving feedback on her book and listening to her responses and ideas. Publishers tend to focus on mobility aids in depicting disability, Keah told me, but when she suggested her picture book display disability without mobility aids, like her own, the team embraced the idea.

Albert Whitman did not respond to my email queries, but Jen Malia told me she had a wonderful experience publishing her picture book Too Sticky! with them:

“What I really loved about working with my book editor, Andrea Hall at Albert Whitman, is that she was really patient with me when I made mistakes. For example, I didn’t track my changes on my draft of Too Sticky! one time. This included me deleting a scene from the manuscript. I had second thoughts and didn’t feel like the scene was an authentic interaction between my main character, an autistic girl, and her classmate. My editor said she thought it was important to show the interaction between them. When I told her what I thought the problem was and suggested a different approach to the scene, she said that worked even better. I felt like we truly collaborated on my book, and she really listened to what I had to say.”

I’ve also noticed an increase in the number of books with disabled main characters published by Albert Whitman, which suggests similar experiences to Jen’s and in-house initiatives to increase disabled diversity. Though I want to add that Albert Whitman has a history of failing to pay authors.*

How The Children’s Book Publishing Industry Could Be More Inclusive Of Disability

“Nothing about us without us.” —Raymond Antrobus

Hire More Disabled People

“The book publishing industry needs to hire more disabled people who are gatekeepers — from agents to editors to publicists to the highest positions within publishers — so disabled authors can be give the space to publish authentic books.” —Jen Malia

“I believe the biggest problem in publishing is that decisions on what titles are published and which ones are not are made in a closed room of cis-gendered, temporarily able-bodied, White people. What if the decision-makers decided what books were published based on what titles were missing (especially when looking at global demographics) and what people were asking for?” —Brittany Murlas, Founder of Little Feminist and publisher of We Are Little Feminists: On-the-Go

While all publishers claim to be open to hiring disabled people, few initiate specific protocols that would welcome disabled writers. Topping the list is allowing workplaces to be remote. The past year has proven that remote work is possible, yet every new job listing in publishing states “currently remote, but must live in NYC for when the company returns to office” (or another city, but usually NYC). Alaina Lavoie discusses this issue in a recent article for Publisher’s Weekly:

“If there’s a lesson that publishers can learn from this pandemic, it’s that our industry needs more remote-friendly opportunities if we want to address the widespread ableism and inequality in publishing. We need more remote opportunities in book publishing. Of 166 recent job listings for positions at Hachette, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, Scholastic, and Simon & Schuster, only two specify that they are open to remote candidates, and one of those two is a contract position, not a full- or part-time job.”

Remote work is the best and most inclusive way to open up publishing to disabled people. If publishers aren’t open to remote work, then they’re not creating a welcome environment for disabled folk.

And hiring disabled people will mean having their much-needed perspective on disabled narratives.

Have An Individualized Approach For Working With Disabled People

“I think asking their authors what they need is key. As long as the industry is attentive and willing to bend according to what each individual needs, we’ll be in good shape! There’s no one size fits all approach to disability; everyone has a unique experience. So being open and willing to work with the author is very important.” —Jessica Lewis/Jazz Taylor, author of Meow or Never

“Often, people are looking for a checklist of things they can do to make sure they’re being accessible, but the reality is that it varies from person to person and even two people with the same disability aren’t the same. So it makes more sense to have a flexible attitude at your publishing house with an individualized approach: Do your processes actually have to be identical for all employees, or all authors and illustrators? Or can you accommodate, for example, phone conversations for someone if email doesn’t work for them?” —Alaina Lavoie

Both Keah Brown and Jen Malia shared how having an individualized approach to their books made the publishing experience so much better. Listening, valuing each individual, respecting their needs, these should all be basic tenants of working with disabled people (and really every person), whether they’re employees in the publishing industry or authors and illustrators.

Publish More Books With Disabled Characters That Aren’t “About” Disability

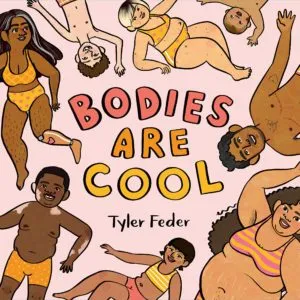

“I would love to see more disability representation in books that aren’t specifically about disability. Of course books that help kids learn about disability are so important and needed, but it would also be great for kids to see disabled characters (especially disabled main characters) with storylines about friendship or magic or monsters too!” —Tyler Feder, author and illustrator of Bodies Are Cool

While many of the authors I spoke to mentioned they’re seeing more books with disabled characters that aren’t “about” disabled characters, it’s still rare. I also cover fantasy and science fiction, and I can attest to how rare it is to see a disabled main character fighting dark magic or riding dragons.

Publish More Books By Disabled Creators

This is a very long excerpt from my conversation with disabled literary agent and children’s book author James Catchpole, but I thought he perfectly described why #OwnVoices creators are necessary in diversifying publishing, and how they can bring more to publishing than disability-adjacent creators. That doesn’t mean that disability-adjacent creators can’t write good and nuanced books with disabled main characters, but that disabled creators should be a bigger part of the story, and they’re also less likely to use harmful stereotypes in their books.

“I think the best thing the industry could do would be to start taking disability seriously, as a subject. By this I mean: stop allowing it to be used by writers as a literary device (as crude metaphor or a tool for emotional manipulation, be it for pity or malice or inspiration) and start thinking of it as a specialist subject, on which a level of expertise is required on the part of the writer.

“Where an author writes about a brain surgeon, then assuming they’re not a brain surgeon, we expect them to do their research. Where they write about a wheelchair user, then assuming they’re not a wheelchair user, we expect them to wing it, and make up any old clichéd rubbish from the accumulated stereotypes knocking around in their unconscious.

“This used to be the attitude with white authors writing characters of colour, and I’d say there’s been a long-overdue reckoning on that score. Could we have the same for non-disabled writers writing disabled characters, please?

“Maybe one more thing, as a continuation of the above. Perhaps the reason things have been slower to change with disability than with race, in that regard, is that the industry tends to give non-disabled people who may be disability-adjacent an unearned degree of authority, both as creatives and as so-called ‘sensitivity readers’ (dreadful term!). I think this happens because of the role of groups around disability — whether charities, the medical profession, or families of disabled people.

“I need to be clear that I’m not saying non-disabled people should never be writing books about disabled characters. It’s not as simple as that. As an agent, though, I regularly receive stories on submission from disability-adjacent people. I completely understand the impetus and the good intentions that drive them to write these stories. They want disabled children to feel represented in the books they read, and they quite rightly see how thin the selection currently on offer is — so of course they wish to address this…

“But being adjacent is not the same thing as having that experience yourself, and the great majority of stories I’ve read by disability-adjacent people follow the same path as books by well-meaning professional writers who are not themselves disabled: almost always, the disabled child either isn’t centred in the story, or they aren’t given real agency in the plot…or there just isn’t a plot, but a slightly empty message instead (usually something like: disabled kids are kids too! Which honestly I’d hope we could take as read).

“My wife Lucy is a wheelchair user, and as a disabled couple we have waded through a great many picture books that touch on disability — the great majority by non-disabled authors — and there are so few that, for all their good intentions, don’t actively perpetuate harmful stereotypes. She’s posted about those happy few on our Instagram @thecatchpoles, under the hashtag #KidLitCripCrit, for anyone interested.” [On a personal note, I love their Instagram]

“It is possible to address the subject of disability well in writing for children, as a non-disabled writer. We’ve an old favourite from the 90s, Mama Zooms by Jane Cowen-Fletcher, where a non-disabled child delights in riding on his mother’s wheelchair – something we well know to be true!

“But what we really need is stories from the perspective of disabled children – stories that centre disabled characters. We’d like to see the industry heed the call for #OwnVoices, by finding and supporting writers who were those disabled children, to write those books.”

Work With Disability Organizations

“I think it would be incredibly exciting to see increased coordination between publishing and the many wonderful national and international organizations out there dedicated to disability rights and advocacy. I think everyone in publishing is always looking for positive ways to expand and reach outside the publishing ‘bubble,’ and when it comes to disability representation, this might be one way of doing that!” —Sarah Allen

Publishing companies could work with disability organizations in numerous ways: conducting anti-ableist training like Candlewick; publishing books together; accessibility discussions for both in-house hiring and in printing books; having a book series chosen by these organizations. The possibilities are endless.

Hire Sensitivity Readers

“After I finished the initial round of illustrations, I worked with a wonderful disability sensitivity reader, Rabbi Ruti Regan, who gave me so much helpful feedback on how to refine my depictions of disability (like adjusting how a wheelchair fit a particular character’s legs). Rabbi Regan also completely opened my eyes to ways of including autism representation in the book, like having a character on the ‘hands’ page drawing a repetitive pattern. I feel really grateful for her help!” —Tyler Feder

I was actually surprised more of the creators I interviewed didn’t mention sensitivity readers, and I think that’s because sensitivity readers are one way to be inclusive, but it shouldn’t be the only way a publishing company ensures their books don’t contain harmful stereotypes. I take work sometimes as a sensitivity reader, and I’ve had mostly positive interactions, particularly with individual authors. Authors have been very happy to implement my suggestions and to do additional research. I’ve worked with publishing companies twice, and in both instances I felt like they did the minimum after receiving my feedback. It feels more, from my limited perspective, that when a publishing company hires sensitivity readers, it’s to check a box, while when individual authors hire me, it’s to ensure their books are accurate and in no way cause harm to the disabled community.

Tyler’s experience working with a sensitivity reader shows how they can add to the process. Her picture book Bodies Are Cool depicts many different types of bodies and disabilities, so it was necessary for her to do a lot of research into many different disabilities to portray them in her illustrations accurately.

Literary Agents: Be Willing To Work With Disabled Creators

I’m a member of several groups of disabled creators, and, over the past year, I’ve heard many horrifying stories of literary agents declining to work with an author after discovering they were disabled. This is particularly the case for neurodiverse authors. This should not have to be said, but neurodiverse authors offer a multitude of creative potential for literary agents. Their books offer a unique and needed perspective on the world.

Once again, having an individualized approach is best. Here is Jen Malia describing working with her agent:

“When I was working on a different picture book manuscript also with an autistic girl as the main character, my agent, Naomi Davis at BookEnds Literary, suggested making some cuts to a scene to clarify why my character had an autistic meltdown. I explained why I thought the meltdown probably wouldn’t have happened at all without the complexity of what was going on in the scene. She agreed with me, and we left it in with some other tweaks. My agent knows my perspective as an autistic person is important to making my books authentic.”

Literary agent Eric Smith recently conducted a Twitter survey about how literary agents can better serve neurodiverse writers. His blog on the results can be found here. I highly recommend all agents read it.

Make Conferences Accessible

This has already been mentioned above, but I also wanted to note that inaccessible publishing industry conferences are also barriers for disabled folk who want to work in the industry. All conferences need to be made accessible, and people who run conferences need to investigate how they can make that happen.

What Are The Implications For Readers?

Readers, whether you’re disabled or not, you need to read books with disabled characters. I think readers know and already want that!

When I spoke with Brittany Murlas, the founder of Little Feminist, about her book On-the-Go (which Book Riot editor and contributor Kelly Jensen discusses here), she told me that when the Little Feminist company began trying to find diverse books for their children’s book box, they found zero board books featuring disabled characters. Zero. “And 100% of children’s books we found featuring people with disabilities were about how they overcame/survived their disability (the one exception is Mama Zooms), portraying disability as a problem to be solved, as opposed to showcasing people with disabilities living their lives and thriving just like any other story would,” she added. Considering that 26% of the population is disabled, this is ridiculous.

Readers want and need disabled characters in their books. Readers, while you’re not in charge of who publishing companies hire, you can show them you want more disabled representation in your books by buying #OwnVoices children’s books by disabled main characters, asking your library to purchase these books if you’re unable to afford them yourself, and even writing emails to your favorite publisher, or tweeting them, that you want #OwnVoices disabled representation.

If you’re needing some book suggestions, check out all the books I’ve mentioned in this piece, my list of children’s and middle grade titles, and these two lists of YA novels with disabled characters.

*Editors Note: Information about claims against Albert Whitman for failure to pay authors came to light, and was added to the piece, shortly after its publication.