Dictionaries to the Rescue: On the Importance of Words in a Post-Truth Era

In his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language, George Orwell discusses the consequences and causes of sloppy language. It’s a vicious cycle:

“[Language] becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.”

In this “post-truth” age of “alternative facts”, when we can’t seem to agree on the most basic principles, Orwell’s essay is more relevant than ever. We are hungry for accurate language, desperate to find some way to at least agree on what words mean, even if we can’t agree on anything else.

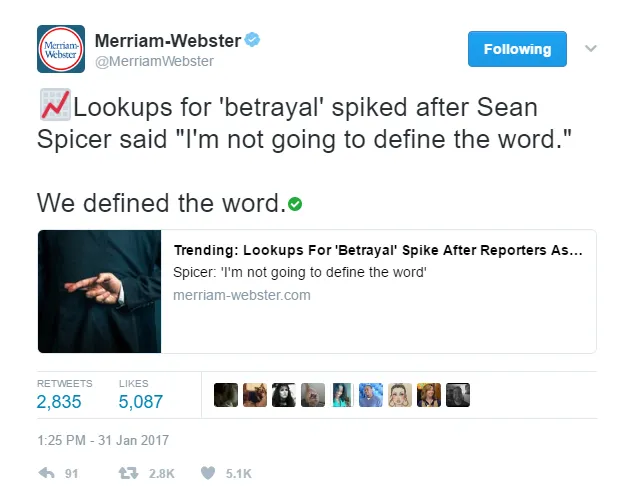

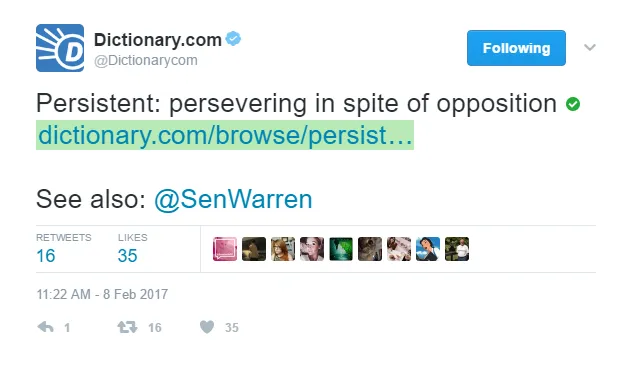

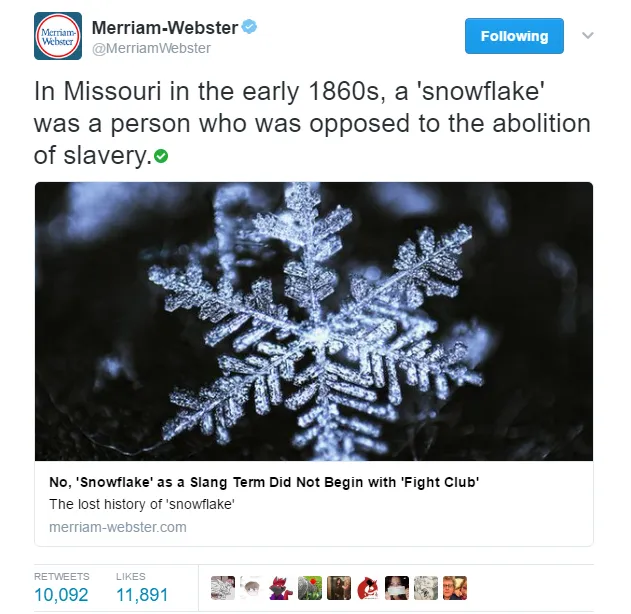

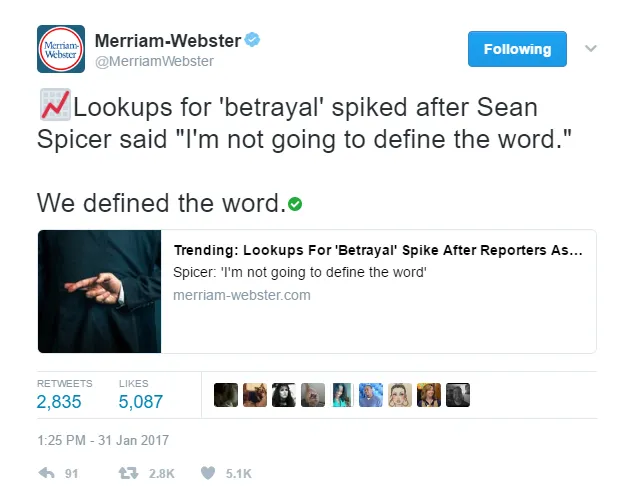

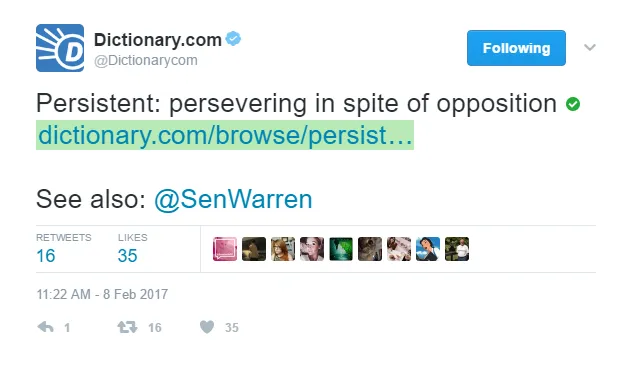

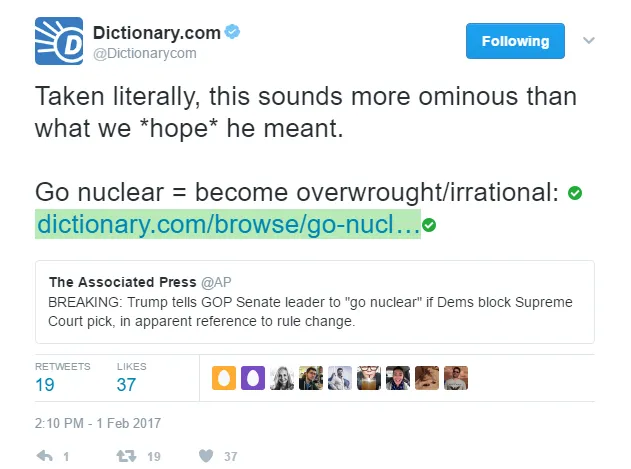

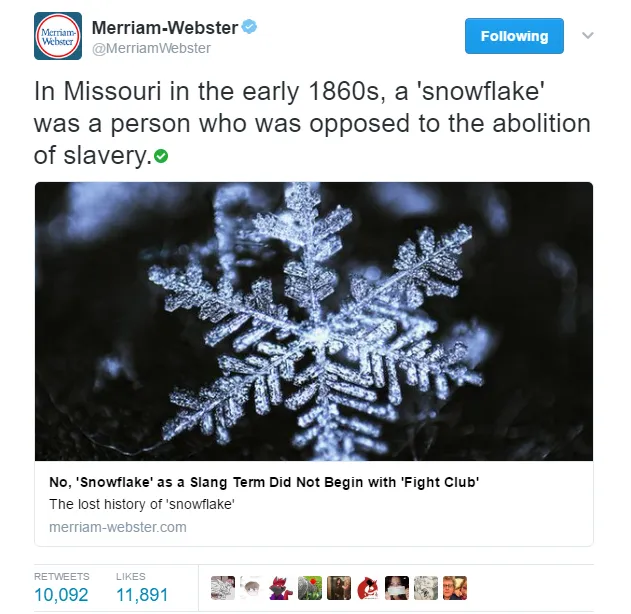

Dictionaries, the stuffy authorities of the grade school classroom, are stepping up into the gap. As Katherine Rosman wrote in a recent New York Times article, dictionaries are making a comeback. People are returning to them as a touch-stone of authoritative knowledge. A dictionary is no longer simply a book that is too big to fit into your purse; it’s an active presence in political discourse, entering the conversation in real-time on social media. Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) and Dictionary.com (@Dictionarycom) are not only defining words, but also providing biting political commentary.

Dictionaries, the stuffy authorities of the grade school classroom, are stepping up into the gap. As Katherine Rosman wrote in a recent New York Times article, dictionaries are making a comeback. People are returning to them as a touch-stone of authoritative knowledge. A dictionary is no longer simply a book that is too big to fit into your purse; it’s an active presence in political discourse, entering the conversation in real-time on social media. Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) and Dictionary.com (@Dictionarycom) are not only defining words, but also providing biting political commentary.

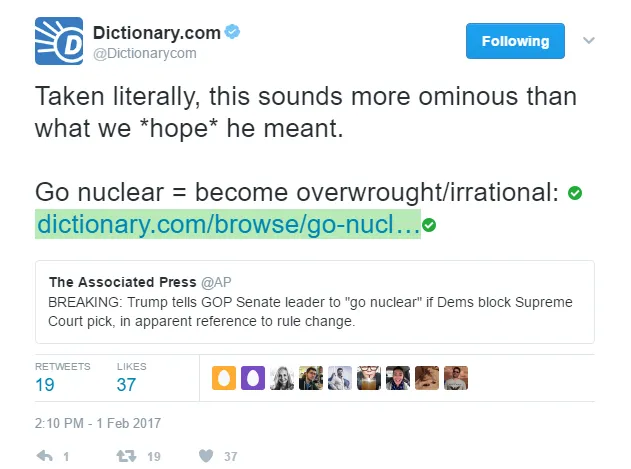

Rosman reports that, according to the head of Dictionary.com’s marketing department, “the intent is not to be political or partisan”, but rather to “demonstrate the relevance and usefulness of an expanded vocabulary”. This may be true, but here’s the thing. Language, and our use of it, is inherently political. In an atmosphere of confusing rhetoric and blatant falsehoods, the very act of defining a word is political. Rooting out bad habits in language is essential in the fight against oppression.

Rosman reports that, according to the head of Dictionary.com’s marketing department, “the intent is not to be political or partisan”, but rather to “demonstrate the relevance and usefulness of an expanded vocabulary”. This may be true, but here’s the thing. Language, and our use of it, is inherently political. In an atmosphere of confusing rhetoric and blatant falsehoods, the very act of defining a word is political. Rooting out bad habits in language is essential in the fight against oppression.

As Orwell says, “If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.”

As Orwell says, “If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.”

If you needed any proof of the power of books, here it is. Words, and how we use them, matter. Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster are not just entertaining and informing us. They are taking an essential step towards freeing us: giving us the tools, the words, to free ourselves. This is important work, and in a world where the president of the United States is a Twitter troll, it’s risky work that takes bravery and stamina.

If you needed any proof of the power of books, here it is. Words, and how we use them, matter. Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster are not just entertaining and informing us. They are taking an essential step towards freeing us: giving us the tools, the words, to free ourselves. This is important work, and in a world where the president of the United States is a Twitter troll, it’s risky work that takes bravery and stamina.

These dictionaries are part of a community of people and organizations with the audacity to use words with precision in the face of mendacious power. Where words come from and what they mean matters. The history of a word is the history of a concept, and that’s the foundation of our ability to talk about anything. Certain forces would like to redefine key concepts like racism and religious freedom. Dictionaries are on the front lines of that battle. They may not have set out to be political, but like many other respected institutions (e.g. libraries and schools), at the moment the very act of continuing to fulfill their function is political.

These dictionaries are part of a community of people and organizations with the audacity to use words with precision in the face of mendacious power. Where words come from and what they mean matters. The history of a word is the history of a concept, and that’s the foundation of our ability to talk about anything. Certain forces would like to redefine key concepts like racism and religious freedom. Dictionaries are on the front lines of that battle. They may not have set out to be political, but like many other respected institutions (e.g. libraries and schools), at the moment the very act of continuing to fulfill their function is political.

I started out being amused by Merriam-Webster’s tweets, but as time goes on I’m increasingly in awe. As a writer and reader, I believe in the power of words to help carry us through this turbulent moment in history. It’s incredibly comforting to know that those benevolent linguistic deities of my childhood, the reliable old dictionaries, are on side.

I started out being amused by Merriam-Webster’s tweets, but as time goes on I’m increasingly in awe. As a writer and reader, I believe in the power of words to help carry us through this turbulent moment in history. It’s incredibly comforting to know that those benevolent linguistic deities of my childhood, the reliable old dictionaries, are on side.

Dictionaries, the stuffy authorities of the grade school classroom, are stepping up into the gap. As Katherine Rosman wrote in a recent New York Times article, dictionaries are making a comeback. People are returning to them as a touch-stone of authoritative knowledge. A dictionary is no longer simply a book that is too big to fit into your purse; it’s an active presence in political discourse, entering the conversation in real-time on social media. Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) and Dictionary.com (@Dictionarycom) are not only defining words, but also providing biting political commentary.

Dictionaries, the stuffy authorities of the grade school classroom, are stepping up into the gap. As Katherine Rosman wrote in a recent New York Times article, dictionaries are making a comeback. People are returning to them as a touch-stone of authoritative knowledge. A dictionary is no longer simply a book that is too big to fit into your purse; it’s an active presence in political discourse, entering the conversation in real-time on social media. Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) and Dictionary.com (@Dictionarycom) are not only defining words, but also providing biting political commentary.

Rosman reports that, according to the head of Dictionary.com’s marketing department, “the intent is not to be political or partisan”, but rather to “demonstrate the relevance and usefulness of an expanded vocabulary”. This may be true, but here’s the thing. Language, and our use of it, is inherently political. In an atmosphere of confusing rhetoric and blatant falsehoods, the very act of defining a word is political. Rooting out bad habits in language is essential in the fight against oppression.

Rosman reports that, according to the head of Dictionary.com’s marketing department, “the intent is not to be political or partisan”, but rather to “demonstrate the relevance and usefulness of an expanded vocabulary”. This may be true, but here’s the thing. Language, and our use of it, is inherently political. In an atmosphere of confusing rhetoric and blatant falsehoods, the very act of defining a word is political. Rooting out bad habits in language is essential in the fight against oppression.

As Orwell says, “If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.”

As Orwell says, “If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.”

If you needed any proof of the power of books, here it is. Words, and how we use them, matter. Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster are not just entertaining and informing us. They are taking an essential step towards freeing us: giving us the tools, the words, to free ourselves. This is important work, and in a world where the president of the United States is a Twitter troll, it’s risky work that takes bravery and stamina.

If you needed any proof of the power of books, here it is. Words, and how we use them, matter. Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster are not just entertaining and informing us. They are taking an essential step towards freeing us: giving us the tools, the words, to free ourselves. This is important work, and in a world where the president of the United States is a Twitter troll, it’s risky work that takes bravery and stamina.

These dictionaries are part of a community of people and organizations with the audacity to use words with precision in the face of mendacious power. Where words come from and what they mean matters. The history of a word is the history of a concept, and that’s the foundation of our ability to talk about anything. Certain forces would like to redefine key concepts like racism and religious freedom. Dictionaries are on the front lines of that battle. They may not have set out to be political, but like many other respected institutions (e.g. libraries and schools), at the moment the very act of continuing to fulfill their function is political.

These dictionaries are part of a community of people and organizations with the audacity to use words with precision in the face of mendacious power. Where words come from and what they mean matters. The history of a word is the history of a concept, and that’s the foundation of our ability to talk about anything. Certain forces would like to redefine key concepts like racism and religious freedom. Dictionaries are on the front lines of that battle. They may not have set out to be political, but like many other respected institutions (e.g. libraries and schools), at the moment the very act of continuing to fulfill their function is political.

I started out being amused by Merriam-Webster’s tweets, but as time goes on I’m increasingly in awe. As a writer and reader, I believe in the power of words to help carry us through this turbulent moment in history. It’s incredibly comforting to know that those benevolent linguistic deities of my childhood, the reliable old dictionaries, are on side.

I started out being amused by Merriam-Webster’s tweets, but as time goes on I’m increasingly in awe. As a writer and reader, I believe in the power of words to help carry us through this turbulent moment in history. It’s incredibly comforting to know that those benevolent linguistic deities of my childhood, the reliable old dictionaries, are on side.