Chatting About Evolution, One Neighborhood at a Time

I got my English degree at a very small public liberal arts college out on the prairies of Minnesota. One of the best parts about going to such a small college is the chance to connect with professors one-on-one or in small classes, something that’s hard at big schools. Our college also emphasized interdisciplinary studies — tackling subjects from different vantage points and points of view.

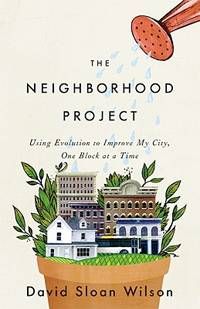

Reading The Neighborhood Project by David Sloan Wilson was like going back to college for an interdisciplinary independent study with a favorite professor. The ostensible topic of the course is the use of evolution in community development, but each week (or, in the case of a book, each chapter) approaches the topic from a different angle. Over the course of the semester, a student starts to notice the professor’s little quirks and favorite phrases, connections between seemingly dissimilar topics, and are left curious to dig more deeply into the research on a particular topic in their own time.

Wilson is an evolutionary biologist who has spent years studying evolution in the animal kingdom. About five years ago he decided the best way to test out Darwin’s theories about evolution would be to see if they can be used to improve human life in a practical way. Thus began the Binghampton Neighborhood Project (BNP) — an effort to collect data on Wilson’s hometown, then use evolutionary theory and the data to make his community better.

Wilson is an evolutionary biologist who has spent years studying evolution in the animal kingdom. About five years ago he decided the best way to test out Darwin’s theories about evolution would be to see if they can be used to improve human life in a practical way. Thus began the Binghampton Neighborhood Project (BNP) — an effort to collect data on Wilson’s hometown, then use evolutionary theory and the data to make his community better.

As someone who has always been interested in the ways lessons learned in academic research can be used in the real world, I felt like this was a book I had to read. While I had some disappointments with the execution of the book, on the whole I found it an engaging survey of the scientific method and the current state of evolutionary theory research in different academic disciplines.

For a book titled The Neighborhood Project, Wilson’s BNP is surprisingly absent. Discussions about the project loosely connect to many of the chapters, but the book reads more like a memoir about several years of research for an active and engaged evolutionary scholar where the BNP is just one of many interests that gets explored. For a book that serves as a survey course of evolutionary research and applications, that’s ok, but I was really hoping for an in-depth look at the BNP. In that sense, I found parts of the book disappointing.

However, the book did hit on my fascination with learning about how things work; in this case, Wilson does a remarkable job of demystifying both science and scientists. He also includes a number of short biographies of scientists in his field or that he has run across in his research, which he uses to show how anyone can become a scientist, and that the field is open to anyone willing to constantly question assumptions and work within the scientific method.

Overall, I think it was Wilson’s tone that made the book feel so much like a class with a favorite professor rather than a dry, academic text (even though plenty of the subjects touched on in and of themselves were a little dry to me). Wilson has some really delightfully elegant phrases to describe phenomena — “the pinball machine of life” and “the hammer of natural selection” come to mind — but has a tendency to overuse the phrases to the point that borders on annoying. On the plus side, Wilson is also not afraid to equally compliment and criticize other scholars for the good and bad he sees in their research. As a non-scientist, I felt like I was getting an inside look at the world of the scientific establishment.

If there’s a single take home message of the book, it’s that Wilson believes any topic can be approached from an evolutionary perspective. Evolution can apply to our genes, our psychology, and our communities, and it is our job to understand the processes so we can use them effectively to promote positive changes. As Wilson elegantly explains near the end of the book:

Genetic evolution is fast enough and cultural evolution is slow enough for the two to become entwined in a double helix of their own. Both our genes and our cultures have served us well in the past — we’re here, after all — but there is no guarantee that they will serve us well in the future. Evolution has no foresight, regardless of whether it is genetic or cultural. It’s up to us to become wise managers of evolutionary processes, which requires understanding the complex interactions among our genes, our cultures, and our lives.